Analyzing DoD’s Sustainable Energy Practice

US. Armed Forces “own” the largest number of the 500,000 Federal buildings; 600,000 vehicle fleet and 1.8 million Federal employees. Therefore, it only makes sense that a national policy for energy independence, security and efficiency be implemented by the Department of Defense (DoD). Although one would not expect warfighters to be dragged into cost savings and energy economies, sustainability saves lives on the battlefield and has indeed been embraced by deployed servicemen and women.

Culture Change

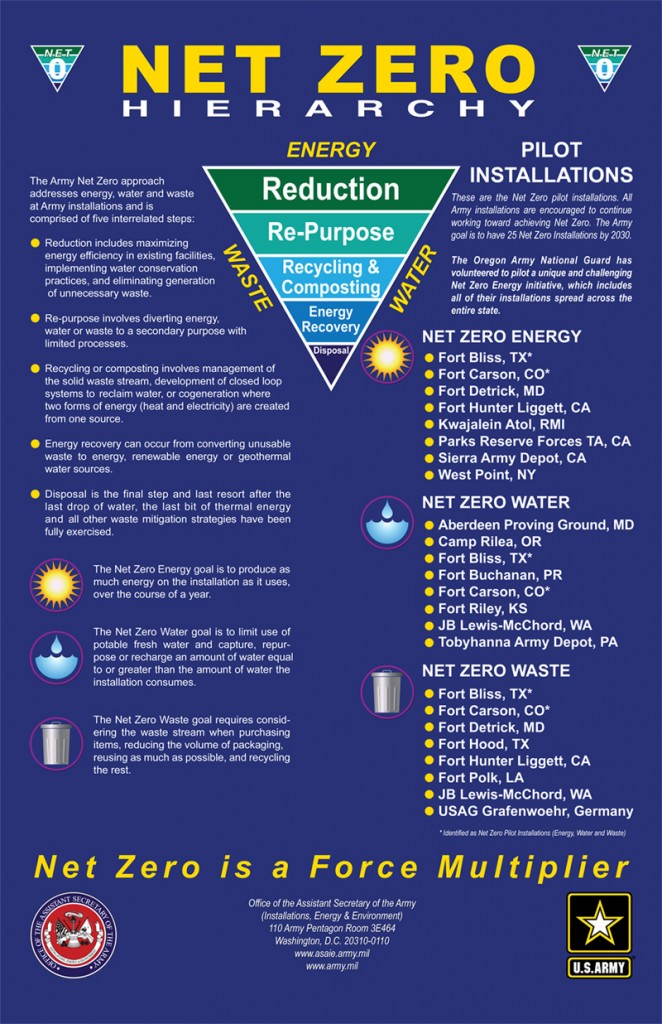

Culture change leaders include Under Secretary of Defense, Installations & Environment (I&E), Dorothy Robyn1 and Katherine Hammack, Assistant Secretary of the Army (I&E). Secretary Hammack developed the Army’s Net-Zero Installation Strategy. The goal is for selected installations to be net-zero, based on net-zero energy, net-zero water and net-zero waste, all striving towards sustainable installations. She said, “We are creating a culture that recognizes the value of sustainability measures in terms of finance, mission capability, quality of life, local community relationships and preserving the Army’s future options.”2

In the public limelight, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus astonished the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC) May 2011 Government Summit3 with his announcement that LEED Gold level certification will be the standard, and that biofuels (from non-food sources) will replace fossil fuels for the Navy.4 He said the dependence on fossil fuel continued to produce bad results during war time by endangering Sailors and Marines charged with guarding convoys bringing energy to bases and by relying on fossil fuel for operational equipment and electric power.5

Today, at least two forward operating bases (FOBs) in Afghanistan are powered entirely by solar energy, and several others obtain at least 90 percent of their energy from the sun. Marine Corps leaders are so pleased with the outcome that they’ve written renewable energy into training plans and doctrine – something Colonel Robert “Brutus” Charette, Jr., director of Marine Corps expeditionary energy, said he hopes will become joint practice with other military services.6

In 2008 DoD spent approximately $20 billion on energy with a significant portion of this (26 percent) on the built environment. Most was fossil fuel from foreign sources, tactical fuel excluded. DoD and the Department of Energy (DOE) were mandated7 to assess energy security, economics, Federal mandates, adjustments to organizations and acquisition methodologies. Their resulting report8 presents a process to examine military installations for net-zero energy potential. This process offers a systematic framework to analyze energy projects at installations while balancing other site priorities such as mission, cost and security. As projects are implemented, net-zero energy assessment measures progress in reducing energy demand and increasing energy self-sufficiency against a baseline benchmark.

The U.S. Army plans, designs and builds facilities using the USGBC Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating tool as a guide and measurement for high performance buildings. In 2011, the Army assessed performance of its new green building culture in its report,9 The Value of ‘Green’ to the Army. This document compares “pre-green” buildings to the current standard and includes the business case for costs and commensurate savings. More importantly, it conveys the health benefits associated with the “green” paradigm for both the occupants and the community. As a result, acquisition methods are now available to facilitate procurement of high-performance buildings and services.

Acquisition Methods

Energy Savings Performance Contracts (ESPCs) are unique contracts that help government reach innovation in the private sector.10 According to Justin Ward, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), they allow Federal facilities to save energy and money at the same time by allowing a private contractor to provide capital to install energy saving infrastructure. The contractor is paid through an agreed-upon monthly amount of guaranteed cost savings and can also take advantage of opportunities that the Federal government cannot, which includes exploiting certain tax incentives, selling renewable energy credits and depreciating property.

Additional cost savings resulting from the new infrastructure benefit the installation and taxpayers. Other than a small supervision and administrative cost, the contractor funds all initial costs for the new infrastructure. This could include upgrading existing heating, ventilation, electricity or water systems; using renewable energy technology; installing better insulated windows and doors or a combination thereof.

The ESPC acquisition methodology has been implemented globally. For example, USACE’s North Atlantic Division (NAD) recently executed a contract at U.S. Army Garrison Vicenza, Italy, where Siemens AG installed a boiler plant that includes a co-generation unit, which will simultaneously produce heat and power by using escaping “waste heat” from electricity production to produce steam to help heat the installation.11 The following are example ESPC projects currently underway at DoD facilities:

- Goodfellow Air Force Base (AFB) took advantage of the ESPC program to solve a cooling problem at one of its specialized campuses. Rather than build a $10 million central chiller plant, the partnership comprised of Air Education and Training Command, the 17th Civil Engineer and Contracting Squadrons, and Siemens Building Technologies Corporation created a “virtual chiller plant” for one-tenth the cost. According to Mike Noret, deputy base civil engineer, “We’re trying to bring private-sector solutions to support our mission and people. ESPCs are a non-conventional, yet cost-effective, financing vehicle that allows us to make much-needed facility repairs with modern, energy-efficient upgrades in an austere funding environment.” Siemens’ $2.6 million ESPC saves $276,000 annually associated with lighting, chilled water and synthetic turf.

- Dyess AFB, among other energy saving initiatives, built an “icehouse” that cools several of its buildings. Water is pumped into the icehouse and chillers freeze it using a water/glycol mix. The resulting slush is then pumped into the building’s air conditioning systems during the day. “We’re saving money here, too, because the chillers are working at night during off-peak hours when electricity is cheaper,” said Tom Denslow, base energy manager.12 Siemens $47.5 million ESPC provided new backup generation; thermal energy; new central plant, HVAC and lighting retrofit; daylight harvest and occupancy sensors; water conservation and energy management systems. Dyess saves $4 million annually in performance improvement thanks to this equipment, which Siemens also guarantees.

- Lackland AFB has a $12.3 million ESPC with Siemens that saves $1.2 million annually, including lighting, solar thermal water heating, chilled water thermal energy storage, and water conservation. Natasha Shah, Siemens director, Federal Energy Division, points out that ESPC projects require commissioning, measurement and verification (M&V protocol), and operations and maintenance as part of the business finance arrangement. This ensures energy savings accountability throughout the contract (which could be longer than 10 years).13

- Siemens and other large firms, like Ameresco Inc., have developed a track record of outstanding partnerships with Federal agencies. For example, USACE selected Ameresco to provide two ESPC service contracts, one for $109 million and the other for $3.6 million. These contracts include a design-build-operate-maintain (DBOM) for a 3.5 million sq. ft. full services repair, overhaul and fabrication facility at Tobyhanna Army Depot. This project also reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 60 percent and saves Tobyhanna $4.9 million in operating costs annually.

© iStockphoto.com/mgkaya

The above ESPC projects are diverse in application, yet each preserves the flexibility necessary to achieve performance guarantees. Flexibility is a strength of ESPCs, but there are also challenges. One challenge is that complex projects require a partner relationship that allows innovation and surrenders many controls more typical of public sector contract specifications. Another attribute of ESPCs is the level of commissioning, measurement and verification (called M&V protocol) required to satisfy the investor and ensure accurate accounting of performance.

Illustrative of a private sector success that would be very difficult to replicate on a typical public sector contract is the New York Times building lighting project. Originally planned to be high-performance, the actual design, installation and commissioning of Lutron’s Quantum total light management system exceeded expectations with 0.396 watts per square foot (rather than the originally designed value of 1.28 w/sq. ft.). This saves more than $600,000 per year (70 percent) in operating costs and 3,200 metric tons of annual CO2 reduction.14 This example required flexibility to make adjustments based on an open system architecture and a knowledgeable commissioning agent (Cx) to optimize the installation and occupant use of the building.

Industry partnerships will help the Army achieve Net-Zero Energy Installations – installations that produce as much renewable energy on site as they use over the course of a year – said Secretary Hammack. These systems include power-purchase agreements (PPA), enhanced-use leases (EUL), ESPC and utilities energy-service contracts that can all help the Army shift to more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly operations during a time of budget constraints. “Over time we would like energy efficiency integrated into everything that we do,” said Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Energy and Privatization Richard Kidd.15

Today, there are 130 ESPC task orders at 60 installations, which will result in a 1.6 trillion BTU energy savings each year. Private-sector investments of this type total $865 million, with $850 million more in development. Especially when the cost of meeting energy-efficiency and renewable-energy goals would not otherwise be feasible given current budgetary constraints, the benefits of partnering with private-sector investors are numerous, according to Secretary Hammack.16

Fast Moving (Maybe too Fast)

The success model for master planning is Fort Drum.17 USACE North Atlantic Division Commander, Brigadier General Peter A. “Duke” DeLuca, is proud that throughout the years solar air heated buildings18 and geothermal19 have been included in realignment to meet current needs and to have flexibility to meet future training missions at Fort Drum. Conversely, when questioned20 about Aberdeen Proving Grounds’ (APG) 14 separate commands, his tone changed as he explained APG’s aggressive Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) mission, 21 with its apparently little time to focus in a unified way on planning beyond the immediate BRAC objective. Throughout the past ten years of war and BRAC, soldier leaders were not developing skills for facilities management as they were for fighting. While morphing into their new alignments, some bases were not taking advantage of the capacity22 to help focus on master planning and sustainability issues.

The demands and challenges in sophisticated markets for complex systems and long-term commitments require mature skill sets for which there is little training for Federal agency employees. This is a compelling reason to leverage private sector expertise and to grow skills internally. One example is implementation with requirements for commissioning,23 measurement and third-party verification required to track progress and to identify opportunities for further improvement. Commissioning sets measureable goals for performance, establishes accountability, identifies and corrects deficiencies for all energy and water systems. It verifies that performance requirements are met throughout design, construction and occupancy, and independently documents delivery of what the owner paid for.

Unfortunately, across Federal agencies this function is too often relegated to the construction contractor budget for execution, thus compromising commissioning agent (Cx) independence. According to Jim Mascaro, vice president for commissioning at McDonough, Bolyard and Peck, “It is in the best interest of the Federal agency for Cx services to be procured directly by the Owner, thereby establishing greater accountability for the systems and components installed by the Construction Contractor.”24

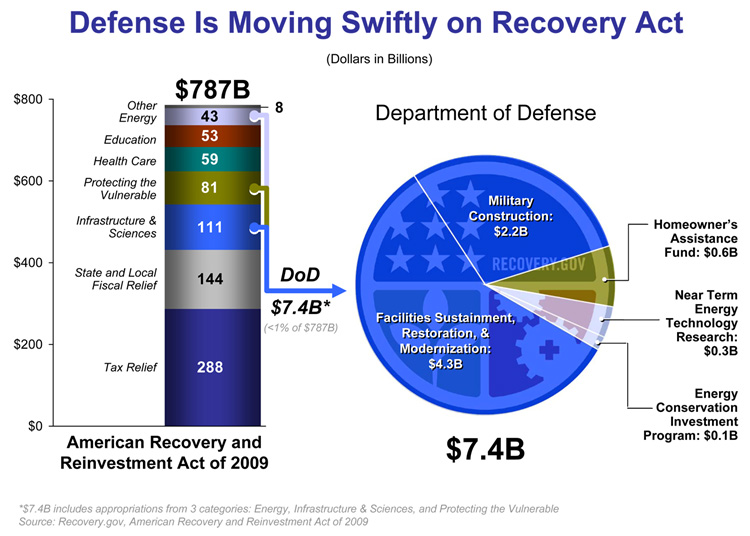

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 funded projects were intended to stimulate DoD programs.25 Army projects26 last year accounted for the following:

- $607 million in facilities sustainment, restoration and modernization projects (FSRM);

- $32 million in energy conservation investment programs (ECIP); and

- $75 million in research development test and evaluation (RDT&E).

According to a DoD March 2009 letter report,27 the expectation was $2.3 billion for military construction and family housing and an additional $3.4 billion for FSRM. A significant number of projects awaiting release of ARRA funds are uncertain at best. Time is of the essence to simulate the U.S. economy and modernize DoD facilities in order to leverage third party financing for ESCO/ESPC, EUL and PPA contract vehicles. Some professionals maintain that ARRA was not as helpful as hoped, and although the author could not find reference to commissioning or reporting requirements that track energy savings in ARRA projects, they surely must be included.

Congress established the Military Housing Privatization Initiative (MHPI) in 1996 as a tool to help the military improve service member quality of life by improving the condition of their housing. The MHPI was designed and developed to attract private sector financing, expertise and innovation to provide necessary housing faster and more efficiently than traditional military construction processes would allow. The Office of the Secretary of Defense delegated MHPI to the military services, and they are authorized to enter into agreements with private developers selected in a competitive process to own, to maintain and to operate family housing via a fifty-year lease. As of March 2011, 188,480 units in privatization projects had been awarded throughout the U. S.28

In the past 15 years, energy and water resource efficiency requirements have matured to encourage more sustainable attributes not initially envisioned. Long-term privatization contracts in place may not support current goals for greenhouse gas emissions and net-zero energy installations. Utility meters are not currently available on most campus settings for individual buildings or residential units. Consequently, innovative incentives are being explored for connecting individual awareness and responsibility to sustainability goals. This is problematic but being addressed.

A Bright Future

U.S. Armed Forces are meeting the challenge for fuel logistics, management and protection of its deployed servicemen and women. Opportunities for distributed generation, tactical grid management, renewable/alternative power and fuels, high performance building and campus complexes, and for leveraging private sector skills and financial resources are all in the playbook with authorities appropriate to the tasks.

There’s more to come on this subject from the author in future issues of livebetter.

Courtesy Photo | 1st Marine Division