Cenotes: Yucatan’s Fragile Wonders

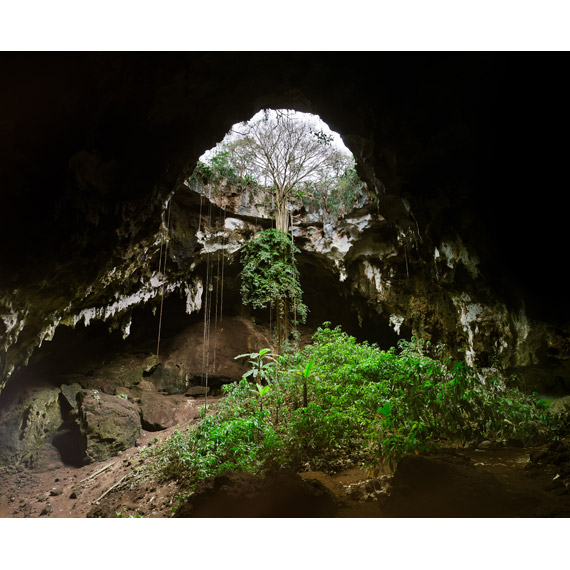

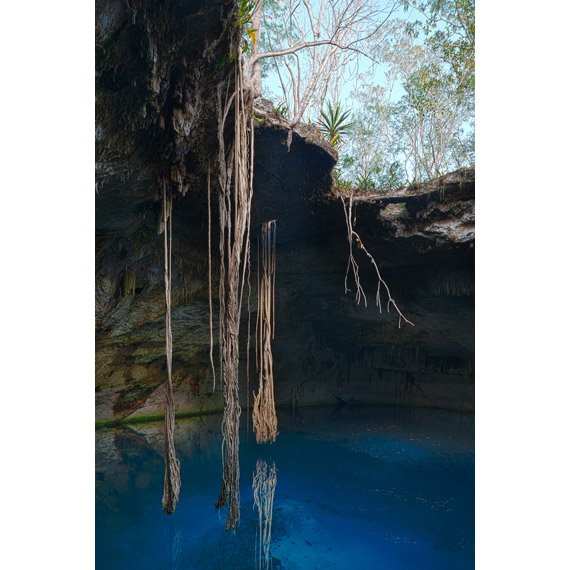

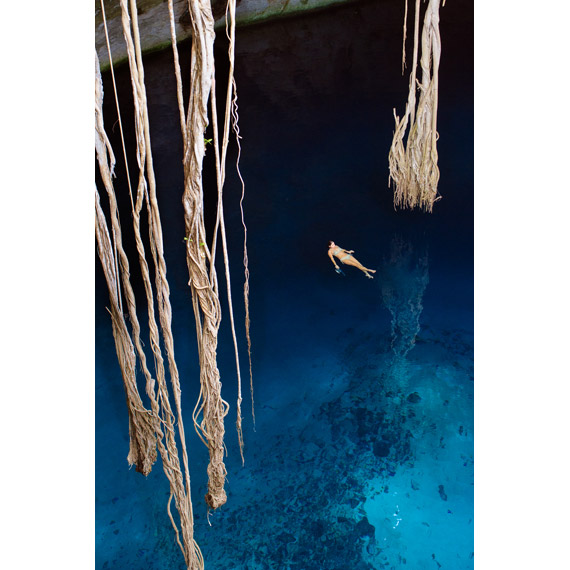

When I first heard the word “cenote” I had no idea what it was. Although I had been to Mexico many times, I never ventured into the Yucatan backcountry. So, when I received an invitation to take part in an International League of Conservation Photographers (ILCP) Rapid Assessment Visual Expedition (RAVE) to the Yucatan, I was eager. RAVEs represent a coming together of talented photographers from around the world to document environmental issues. Photographers specializing in landscapes, aerial, underwater, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects donate their talents to provide professional, high-quality imagery to environmental groups. We came to the Yucatan Peninsula to document its incredible fragile beauty. My part was to focus on cenotes, subsurface portals to an underworld of turquoise waters and hanging roots, using my landscape photography. These virtual gardens lie hidden with plants growing toward a small shaft of light. Stalactites and stalagmites bear witness to the passage of eons of calcium-laden waters migrating through the stone as flowing rivers. These sink holes are also a barometer of the aquatic health of the region. Unfortunately, the story they tell is not good.

Burgeoning hotel growth in the Yucatan and Quintana Roo with only partial sewage treatment is destroying the water that sustained early Mayan civilizations. Not only does the polluted water despoil this underground labyrinth, the natural waters collected in the tropical forest reach into the vast coastal wetlands and the second largest coral reef system. There, pollution can also take a heavy toll.

To experience this underworld, one must check the senses at the door. This is a world with no light. For photographers, working in total darkness is a challenge of the highest order. My first experience of inching forward over slimy rocks was both frightening and intriguing. Once I established that my head was not as hard as the low-hanging stalactites, I began to settle into a rhythm of slowly advancing into the abyss. With one leg forward and one arm extending above my head, my other hand used my tripod as a walking stick to feel the ground ahead. There is dark . . . and there is total darkness. This was total darkness.

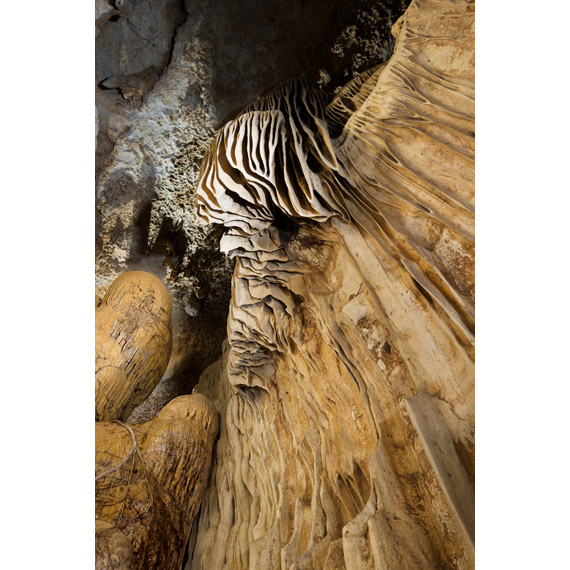

Jack Dykinga|The eons of water shaping the limestone provides tapestries

of sculptured ceiling in this un-named cenote.

My headlamp was only a slight pencil beam bringing my immediate surroundings into semi-lit visibility. As I turned my head, the beam strained forward to illuminate an ever-darkening infinity. I edged forward, feeling the dampness everywhere, but no inkling of a body of water lay ahead. It was my hand and the sense of touch – reaching before me – that first signaled my arrival. My eyes had betrayed me; the clarity of the water allowed my headlamp to see right through the surface and into the cavern below. My hand was submerged before my eyes knew I was in the water!

Alfredo Medina, who literally wrote the book on cenotes, and his wife Sara Fuentes were my guides. Together with Justin Black, we began to unpack an assortment of lights in an effort to beat back the darkness in the 100 foot square vaulted ceiling chamber. Medina brought underwater lights, LED lights and regular flashlights. My plan was to use a combination of strobes, light painting and luck to capture the essence of the place. In a careful orchestration of a synchronized use of several lights, we can unveil what’s absent in murky darkness. There were audible gasps as the lights panned across more and more tapestries of color and texture. After hours of perspiration fogged lenses and staggering humidity, the images came together on the glowing LCD of my Nikon.

Each cenote has its own personality reflecting the Mayan past with names like Papakal, Oxpeejool, Samula, Noh Mason and Calcehtok. Some are vast open caverns large enough to swallow a jumbo jet and overgrown with tropical vegetation. You literally can’t see them until you nearly fall in. Others are tight, sinuous passages with bright texture tapestries of stone. Yet others have one connected room after another – long passageways culminating with collapsed roofs and multiple entrances. I could see the way water circulated through the cavern’s chambers and listened as the gentle dripping from the ceiling offered a hint of the past. Each bend in the passageway offered new surprises and new adventures. I’m addicted!

People ask me why I do what I do. My response is simple: I’m privileged to be in places like this. It’s something that gives meaning to life when I know I’m able to visually share treasures, largely unseen. Cenotes could be lost to unbridled growth. By sharing my images I hope to infect others with my “love of place.” Since finishing the RAVE, I have returned twice more, each time broadening both perspective and knowledge of this parallel universe.

Jack Dykinga|Stalagmites and stalactites with crystal clear tourquise waters

of Cenote Papakal, near Merida, Yucatan, Mexico.

My goal is to bring eco-tourists into this subterranean wonderland, giving the local communities both a source of income and a sense of pride in their unique heritage. It’s a tricky balance of loving a place so much you want to share it vs. preserving the delicate features from masses of tourists. However, giving economic value to special places not only underscores the need to preserve them but also creates advocates who care deeply. For more information, go to www.visionarywild.com.

We photographers from the iLCP are nothing without the NGOs and local organizations that share their treasured locations and that continue the effort to educate through images and, thus, change people’s behavior. It’s their land and we must respect their wishes. One example, Amigos de Sian Ka’an, a Mexican NGO with 25 years of environmental work experience, is developing new ways to interact with nature. They promote state-of the art research in an effort to understand the structure and dynamics of the underground rivers. Amigos are currently using this science to promote construction of wastewater treatment plants along with instituting stronger regulations to return clean treated water to the aquifer.

You can help protect the most extensive underground rivers on Earth. Join and support Amigos de Sian Ka’an. Learn how at www.amigosdesiankaan.org.

The international nature of the International League of Conservation Photographers is reflected in the roster of those taking part in the Yucatan RAVE: Octavio Aburto, Mexico; James Balog, US; Daniel Beltrá Spain; Justin Black, US; Jack Dykinga, US; Patricio Robles Gil, Mexico; Claudio Contreras Koob, Mexico; Garth Lenz, Canada; Balan Madhavan, India; Thomas Mangelsen, US; Cristina Mittermeier, Mexico; Robin Moore, UK; Claus Nigge, Germany; Paul Nicklen, Canada; Pete Oxford, UK; Tom Peschak, South Africa; Joe Riis, US; Kevin Schafer, US; Florian Schulz, Germany; Brian Skerry, US; Roy Toft, US; Michelle Westmoreland, US; and Christian Ziegler, Germany. More information about the iLCP Yucatan RAVE can be found at: http://www.ilcp.com/projects/yucatan-rave.

Jack Dykinga|Intricate shapes and several joined passageways is all that left of an underground waterway.

Jack Dykinga’s Cenote Slideshow