Reordering Life: Contemplate Contentment

Most of us were unconditionally loved and accepted even before we were conceived. We grew and evolved in a protected, ordered and predictable environment where we continued to be loved and accepted for another 36 to 40 weeks. Immediately after birth, a spank on the behind encouraged our first breath into a new and seemingly foreign and chaotic environment different from anything we had experienced before. Some say this first slap is symbolic of trials and tribulations to come. I say it’s a reminder that a physical birth constitutes an awakening to a material reality where order is the complex byproduct of free-will. This changing of the rules of “being” or engagement takes us from a harmonious existence into a seemingly disharmonious one where people are cruel, life is mostly not fair and bad things happen every day. No wonder people, even at an early age, become angry, resentful, bitter and violent.

We begin as net-positive human beings and frequently end up as net-negative ones. Life piles on painful, gut-wrenching experiences and we, inadvertently, incorporate them and their concomitant emotions into our essence. Kind people become mean; gentle people become angry; nonviolent people become violent, and bitterness rules our being without us even knowing it. We become our experiences and forget who we really are. We justify our resentful and, oftentimes, abusive actions by means of religion, ethics or values, even though such teachings are clearly outside our new-found ideology.

Most people I know incur multiple catastrophic, life-defining experiences – those evolving from a healthy and expected “season of mourning” into an unhealthy long-term or lifetime of mourning – which move them toward net-negative outcomes. My life moved in such a direction with the death of my sister in a car accident the day she was to graduate from high-school. She lost control of her Honda Prelude on a typical West Virginia country road, and her car slammed into a tree. The force of the impact threw her out of and under the vehicle, as it turned over and crushed her chest. Her then 18-year old boyfriend, who was still in the car and unscathed, kicked out the back window, exited the wreckage, picked up the Honda and dragged my sister to safety. He didn’t realize she was already dead. That young man, who had already experienced more than anyone should at 18, shot and killed himself a few years later. He was forever heartbroken by my sister’s death and guilt-ridden that he lived.

This was a catastrophic event for me and my family – one which defined us negatively for decades to come. Even so, I knew life would require more because just as death comes to all of us, so does life with its multifaceted variations and uncompromising outcomes. Our spouses, lovers, parents, siblings, children and friends die and/or are ravaged by unspeakable diseases. They endure abusive or otherwise destructive relationships and experiences. We or our children don’t do well in school and are, therefore, imprinted for life as “dummies” or “underachievers.” We lose our jobs, homes, businesses, and sometimes families, not because we don’t work hard and put everything we have into them, but because things happen outside our scope of control. Eventually we gain some semblance of wisdom when we begin to understand that we can’t keep bad things from happening. Life holds all the cards and calls all the plays, and the most we can do is give it our best. But, oftentimes, that realization leads to hopelessness, despair and depression because society has programmed us to believe that our best effort is usually not good enough.

What we don’t realize is that it is good enough; that’s all we’re ever supposed to do – give it our best. No amount of obsessive compulsive behavior, such as working 12-to 18-hour days every day, giving up all the joy in life or working toward perfection (since perfection is not a definable objective) is going to keep bad things from happening.

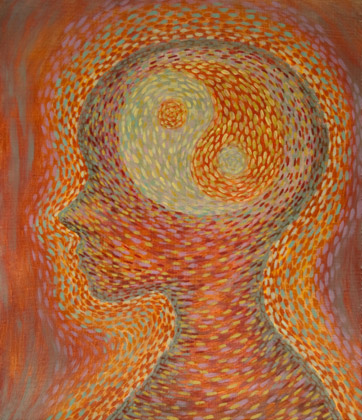

© iStockphoto.com/Jewelee

But, ironically, we can cause the best of the best to happen – things money can’t buy, a poor economy can’t take away and a loved one’s suffering or death can’t separate us from – joy, happiness and contentment. Robert Ketchum, a friend of mine, says, “Choose joy.” It sounds rational, reasonable and common sense; but if you’ve moved away from there a long time ago, it’s hard to find your way back. Sometimes you can’t even remember what it feels like anymore.

My fiancé, who was several years older than me and much wiser, tried to tell me this a few weeks before he died from metastatic carcinoma. He said, “When death comes knocking, you don’t wish you had more time to work. You wish you had more time to spend with the people you love.” He said he wished he had enabled more joy and happiness to enter his life and less regret and resentment. Maybe we do this because we take our natural state, which is love and acceptance, for granted and assume it will always be with us. But, when we spend a lifetime working against that and working toward society’s definition of success, which is material well-being, we forget this most basic part of who we are. The good news is that we don’t lose it; we just misplace it.

Think about what would happen if we backed-off those 12-hour or more work days to reasonable 8-hour work days and spent the other four hours per day working on happiness. I believe our lives and all those in the world would be significantly better. We would require less because we would want less; therefore, we would spend less. Rather than being inside buildings consuming vast amounts of environmentally destructive energy in pursuit of man-made entertainment, we’d be outside in the free world of nature, sucking up its healing, inspirational and awe-inspiring power. We’d also be healthier because we’d be normal weight and less stressed. We’d accept our children’s unconventional choices, and we’d quit suppressing our own regarding who we want to be and how we want to live our lives. As a result, we would evolve a new definition of success, not based on money, which supports diversity and encourages everyone’s unique gifts. No one would become a carbon copy or clone of another, losing their ability to think and reason in the process.

If humans spent more time contemplating contentment, particularly in the United States, we would venture away from material well-being and focus on spiritual well-being. We would find our power in happiness, thereby better enabling us to discard our anger, regret, resentment and our need to control every aspect of life. If everyone chooses joy every time he or she can, we could evolve past the continuum of strife. Then the catastrophic lessons life throws at each of us could be accepted in the spirit in which, I believe, they are offered – as an opportunity to become, through our own pain and suffering, more empathetic, understanding and accepting of others and, thus, more accepting and loving of ourselves for who we are naturally.