Visual Literacy and its Role in Public Schools

In a collaborative, brainstorming environment, it is impossible for children to make a mistake. This is the first of several beliefs taught in “See • Hear • Feel • Film” (SHFF), a writing-based visual literacy program for third grade students. Beginning with the 2001 Jacob Burns Film Institute in Pleasantville, N.Y., SHFF has been implemented into the curriculum for more than 40,000 students nationwide. Both a creative outlet for youth and a collaboration between communities and public schools, the program challenges traditional curriculum’s lack of media education. As such, SHFF encourages young people to take active ownership of media and to become critically informed of the world around them. The 2012-2013 academic year will bring nearly 1,400 third graders to Amherst Cinema, a non-profit movie theatre in Amherst, Mass., for SHFF’s second consecutive year at the location.

Steve Apkon, executive director for the Jacob Burns Film Institute, conceptualized the educational program for third grade students and enlisted Anne Marie Santoro, director of Educational Programs and Outreach for Children’s Television Workshop (CTW), to develop the curriculum. Apkon wanted the program to focus on two main objectives for students: 1.) for children to become more critical viewers of all visual media and 2.) for the program to help eight- and nine-year-olds lead more examined lives.

When Apkon hired Santoro as a SHFF consultant, she was delighted. “I felt every experience I ever had in education and communications had prepared me to bring this curriculum into the world,” remembers Santoro. Founder of several media education projects, she started “From the Heart Communications,” in Manhattan, N.Y., in 1989 to create educational media that “nourished the human spirit.” Santoro also created nationwide school and community programs around Sesame Street, 3-2-1 Contact and Square One TV to ensure these shows had a positive impact on viewers.

“In third grade, students aren’t babies, and they aren’t big-shots. They’re still connected to their authentic, original voice. It’s the perfect moment to celebrate their creative expression before they begin considering what other people will think about it,” explains Santoro.

Santoro chose films from around the world for the program, including an Iranian film, which students watch in Farsi, and a Danish film shown in German, both with English subtitles. Students instantly connect with young, main characters whose central conflicts are similar to their own. The main character in the Danish film moves with her family against her will from the city to the country, and she misbehaves as a result. The second short film features a blind child whose father is late picking him up from school. Rather than sitting idly in fear, the boy explores his environment and gains a thorough understanding of his surroundings. By identifying with main characters, students recognize their own ability to tell stories through words and moving images.

“I believe creative expression is at the center of education in our multi-cultural democracy. The ability to effectively communicate with ease is the key to creating a life that contributes to the health of our culture.

© iStockphoto.com/ASIFE

We designed SHFF to help eight- and nine-year-olds write with clarity, confidence and joy by teaching them the tools filmmakers use to tell a story. Our goal is for them to feel more powerful as writers and storytellers,” Santoro vividly explains.

In the case of Amherst Cinema, one of the emphasized goals of SHFF is to put young people in the seat of filmmaker rather than audience member. During the program each third grade class watches four films. As the lights come on in the theater, students are invited to recall and to analyze what they have seen. Films are then played a second time for a deeper, more critical viewing.

“We begin engaging with media almost instantaneously, and yet we don’t actually start formally training our students until they get to college,” says Allison Butler, lecturer on communications at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is also on the steering committee of the Massachusetts Media Literacy Consortium (MMLC), an organization working to bring media literacy education to public school students from Pre-K to 12th grade. “We have 18 years, potentially, of media engagement without media learning. We would never do that with math; we would never do that with science,” contends Butler.

In 1992, a convention at the Aspen Institute in Maryland invited scholars to make sense of and to incorporate media literacy – the ability to access, analyze and produce media – into the U.S. educational agenda. To date, no formal requirement exists to teach media literacy in public schools.

Though SHFF is mainly geared toward sparking creative expression in third graders, critical analysis of media inevitably takes place throughout the program. The focus is critical but not necessarily negative. “I’m not the morality police. I want children and teenagers to be able to make more informed choices. If they choose to continue engaging with media, whether it’s video games, movies, etc., that’s great. To be critical is not to dislike. To be critical is to engage in a three-dimensional conversation,” says Butler.

According to Butler, asking questions is the entry point into media learning. “Third graders have an idea of what they like. They have an idea of what matters to them. But how are they represented? How are stories told about who they are? Who’s making decisions about them? Being directly involved with production of media helps us learn more thoroughly on a multi-dimensional basis and helps our theoretical understanding of it,” she offers.

Jake Meginsky, educational director at Amherst Cinema and SHFF leader, has taught college students as well as seventh and eighth graders in the fields of film, media art and installation art. “I think there’s lots of potential for media education to happen in every grade. Kids are steeped in this stuff. They know the language. They are able to talk; they just don’t have many opportunities to be analytical and critical and to use school time to gain a deeper understanding of what they’re interested in with regards to media. They have a lot of opportunities to talk about books but not a lot of opportunities to talk about movies and television,” comments Meginsky.

Photo Courtesy of Amherst Cinema. | arental permission to photograph granted.

Students from Holyoke’s McMahan Elementary School participate in See • Hear • Feel • Film.

Often donning eye-catching blue sneakers to draw third-graders’ attention to the stage, Meginsky will tell students, “Filmmaking is something that’s available to you and your friends, and it all starts with a great story. We believe great stories live in each and every one of you – not just some of you but all of you.”

In several area school districts, art programs have been discontinued, thus making SHFF one of the few opportunities for some students to leave their town and to gain cultural experiences. One public school teacher, upon her first visit to Amherst Cinema, remarked how some children in her class had never been on a school bus or eaten popcorn before.

Specific outreach has been made by Amherst Cinema through rigorous community fundraising and support to enable students from surrounding underserved school districts to participate in SHFF. Students from these districts (defined as any school whose percentage of children qualifying for free lunch is above 33 percent) account for 75 percent of SHFF participants and are offered full scholarship to the program.

Each district visits Amherst Cinema twice per year, which accounts for the first two of SHFF’s five units. The remaining three units are taught back at school to create something less like a field trip than an integrated experience, using the theater as an extension of the classroom.

“The point is to have them feel like we pulled the curtain back on what goes on in the institution and to help them see that films can come from their imagination, and the screen isn’t far away. The whole time I’m encouraging them to imagine their ideas and their characters up on the big screen. It’s a real invitation for all kids at different stages and engagement levels at school to learn,” explains Meginsky.

Meginsky begins one program unit by turning the film sound off and inviting students to call out what sounds or music they would insert if they were the filmmaker. Throughout the program, students are asked to be decision-makers. “One profound thing that happens is kids’ recognizing there’s a filmmaker. Many third graders don’t know that because images are happening around them so quickly, and it’s so ubiquitous. It can be a profound realization to recognize there’s a human being with intentions behind every image they see,” he comments.

Beyond the students, roughly 70 schoolteachers will receive training at Amherst Cinema through SHFF, which benefits their professional development as educators. “I can’t adequately express both the students’ and teachers’ enthusiasm with the program. I saw teachers integrating the program into their curriculum weeks after their visit to the cinema. [They] saw the explicit connection to the English curriculum they were teaching. This was not an ‘add-on’ but rather a direct support to teaching literacy. It was a way to bring literacy alive through the medium of film,” wrote Holyoke Public Schools ELA/Humanities Director Marie Cole.

Holyoke Public Schools are attended by many students with immigrant parents for whom English is a second language. SHFF’s use of diverse media has changed the way the school system teaches. For instance, SHFF uses storyboards for children to write a component to a collaborative story and to draw a corresponding image. Since their introduction, all Holyoke Public Schools now use storyboards in their classrooms. “I think images are the great leveler, so this works for kids from all different circumstances,” says Meginsky.

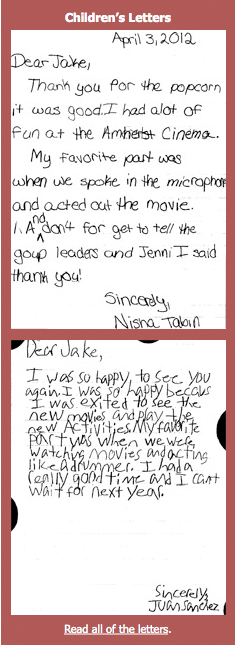

Proof of SHFF’s resonance with the students comes back to the cinema in the form of journals that Meginsky hands the children as they leave. Inside the journals are blank storyboards and lined paper, which are often returned full of stories. In addition, students send letters proclaiming SHFF as the best field trip they’ve ever taken and expressing their anxiously awaited return for the program’s second unit. One student writes, “You were a really good facilitator, Jake. I can’t wait to go back to Amherst to learn more.”

Proof of SHFF’s resonance with the students comes back to the cinema in the form of journals that Meginsky hands the children as they leave. Inside the journals are blank storyboards and lined paper, which are often returned full of stories. In addition, students send letters proclaiming SHFF as the best field trip they’ve ever taken and expressing their anxiously awaited return for the program’s second unit. One student writes, “You were a really good facilitator, Jake. I can’t wait to go back to Amherst to learn more.”

Meginsky explains, “Third graders are very literal about expressing their joy. Every letter mentions the popcorn.”

SHFF is aligned with the 2010 Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science and Technical Subjects, which pinpoints confidence in literacy as a push toward success for public school children. The program invites critical inquiry, yet it mostly aims to empower students. Meginsky and program volunteers – college students, retired educators and adults from the community – work to make Amherst Cinema an emotionally safe environment for students. Children leave with a sense that they have communicated their talent and intelligence to the adults, and they are respected, powerful and capable.

Besides Massachusetts, SHFF has been implemented in classrooms in Ohio, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The program has also been translated into Spanish and is used in Venezuela, where street children were brought into a boarding school to learn how to lead more literate lives.

“I think we’re all born with the feeling that we have something great and important to say and to tell. It’s important to preserve those feelings throughout education for all kids,” concludes Meginsky.