An Assault on Bristol Bay

Alaska has been home to its fair share of environmental assaults and controversies as a direct result of wars between materialists and conservationists. So in 2008 it’s probably not a big surprise that Alaska is, once again, the center of a contentious environmental issue: the development of a copper and gold mine in the tributaries of Bristol Bay, which is adjacent to the Bering Sea. The proposed project raises many questions of sustainability – from the cultural concerns of tribal peoples who have historically lived off the land to the preservation of what many believe is the world’s most viable, unique watershed. To understand the primary issues, one must first get a glimpse of the uniqueness and grandeur of Bristol Bay.

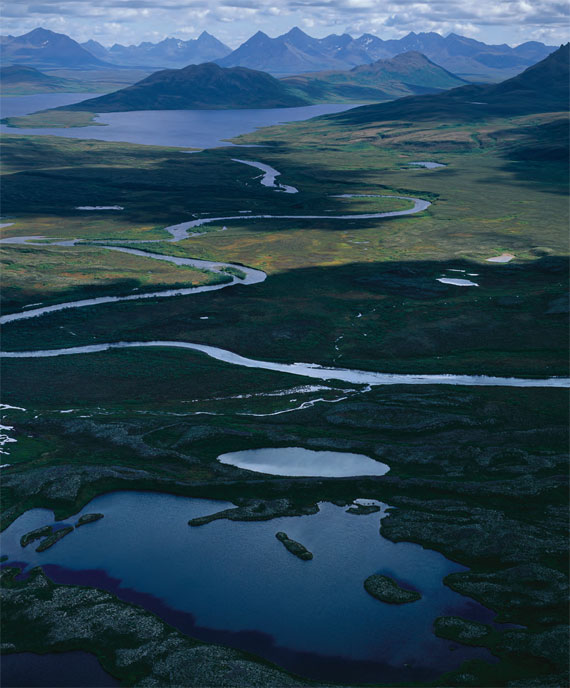

“There are few places left in the world as wild, biologically productive, remote, beautiful, economically important and fragile as the Bristol Bay watershed in western Alaska. The earth’s greatest epic of birth and death takes place here as millions of fish engaged in the planet’s largest salmon run begin and end their lives in the region’s pristine streams and rivers. Humans, brown bears, rainbow trout and numerous other species rely on the bounty of these lands and waters. Without hyperbole this is one of the last great natural places in existence,” explains Deborah Williams, executive director, Alaska Conservation Foundation (ACF), in the foreword to Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery. Photographs by Robert Glenn Ketchum. Essay by Bruce Hampton. Copyright © 2001 by Aperture Foundation, Inc.1

The Uniqueness of Bristol Bay

“Here in the southwest corner of Alaska known as Bristol Bay, in a region about the size of the state of Washington brimming with freshwater lakes and streams, exists one of the earth’s grandest and most spectacular wildlife pageants – one whose numbers exceed the past great migrations of bison . . . and which, in the short history of humankind, has proven far more important. As their ancestors have done for countless millennia before them. . . young salmon will grow and mature over the next few years, descend freshwater streams to the sea, travel over one thousand miles throughout the North Pacific Ocean, then return with remarkable timing and precision to ascend, spawn and die in the waters of their birth.

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

“Although the journey of the salmon is a well-known phenomenon, what isn’t widely acknowledged is that Pacific salmon have disappeared from 40 percent of their original range and their survival is at risk in another 27 percent. In Alaska’s Bristol Bay – home to the world’s greatest wild sockeye salmon population – they still occur in numbers almost beyond belief, both humbling and stirring human imagination,” explains Bruce Hampton in Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery.1

Bristol Bay’s six major rivers, numerous lakes and small streams, most at low elevations and within short distance from tidewater, are what make the region such a vital sockeye nursery. It seems that nature’s perfect blend of location, environment and wild salmon have created an ecosystem laying claim not only to the world’s greatest fishery but also to the largest protected brown bear population in the world. Between 5,000 and 8,000 bears inhabit southwest Alaska and share this unique, vital ecosystem with eagles, otters and the greatest population of large native rainbow trout in the world. All life in this area, including that of humans, is dependent upon the salmon for their survival; thus, the “circle of life” is easily discernible in Bristol Bay.

Given the rugged and remote nature of this area, few humans inhabit Bristol Bay, which is surely another reason why its ecosystem is so vibrant and abundant. For those unaware, the terrain is an exhaustive wilderness with only mostly centuries-old, Alaskan native villages scattered across the region. The closest highway is 250 air miles away, so airplanes and boats are the primary means of transportation. Most of the surrounding area is public land; in fact, 90 percent of the region is comprised of national parks, wildlife refuges, Wood-Tikchik, the nation’s largest state park, and other city, state and federal land. The remaining 10 percent is owned by Alaskan native corporations.

Subsistence fishing is still vitally important to the Alaskan natives – not only for food but also for cultural and social reasons. They are inexplicably tied to the salmon, as they have been since the beginning of their existence. According to Terry Hoefferle, chief executive of the Bristol Bay Native Association, “the salmon are a part of the heart and soul of the region. They make up the bones and blood of everyone in Bristol Bay. We fish them; we eat them; we wait for them to arrive. Without that aspect of the economy, there’s not much else. The thought that the fish won’t return is a terrifying one.” 1

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

Salmon provide economic security to the area, which produces a sustainable industry worth $100 million annually to fishermen. Although this total is enormous, it pales by comparison to the seven-times greater economic gain as salmon pass through and enter the retail market while providing more than 25,000 jobs. This figure doesn’t account for the additional $50 million annually spent locally by Alaskan anglers. Again, none of this economic gain would be possible without the salmon.

Alaska is not only biologically diverse; it is physically diverse with more than 10 percent of the world’s most active volcanoes. The majority of this geological instability lies close to Bristol Bay. In fact, Pavlof Volcano, which is situated at the lower end of the peninsula, has erupted more than 30 times since its discovery in 1778.

The Concern over Pebble Mine

So why would a copper and gold mine in Bristol Bay – the Pebble Mine project – be a topic of conversation, much less a possibility? Would not the thought of losing the salmon, along with the entire ecosystem, be sufficient to render the issue moot? From the perspective of a person with no material gain, this is definitely an insanely ridiculous thing to consider. But unfortunately, from the perspective of those who stand to gain materially, the interjection of a gold and copper mine into a pristine and priceless ecosystem is not only viable but agreeable.

Can a project such as Pebble Mine (projected to be rich in copper, gold and other ores) be designed and managed in a manner that will bring economic gains to the surrounding area without compromising the area’s salmon population? What about the impact on the Alaskan natives and on their traditional way of life – a lifestyle that has existed long before copper, gold and profits were in the American lexicon?

The consensus is that most Bristol Bay residents are afraid of the environmental uncertainty and degradation that mining could likely bring. To them, the economic gains of having a mine are not worth the risk of harming an ecosystem and the people’s ancient way of life, particularly because this lifestyle is tied to their survival and to their culture. Subsistence salmon fishing not only allows many natives to survive; it connects them to their heritage – the same way that it did for their parents and for their ancestors. For the natives, subsistence is about more than food; it’s about self-sufficiency, family, cooperation and outdoor skills. It’s about needing the land more than money. For these people fishing is part of their personal identity; it’s part of their very being. As long as they have the land, they will always survive and never go hungry.

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

Jack Hobson, president of the Nondalton Tribal Council, echoes this thought. His people, too, rely upon the salmon, caribou and the land for their life and cultural sustenance. Hobson and his tribe have been protesting the potential Pebble Mine for more than four years now. He thinks that he not only needs to protect the land and the fisheries from the mine but also the sustainability of his tribe’s future. “I’m connected to Bristol Bay by trying to protect our subsistence way of life,” Hobson said.

In 2007 the American Rivers Organization released its list of the most endangered waterways throughout the United States. Bristol Bay came in at No. 8 because of the potential creation of the Pebble Mine. Amy Kober of the Northwest Region of American Rivers said, “The rivers that feed Bristol Bay support the largest, most productive salmon fishery in the world. An open-pit mine in the headwaters of the Kvichak and Nushagak rivers is a wildly risky gamble that threatens a lucrative fishing industry, our natural heritage, clean drinking water and the well-being of local communities. There are so few places in the world where wild salmon runs are still strong and healthy. Bristol Bay is no place for a mine. Its rivers and salmon are truly more precious than gold.”

American Rivers is not the only organization that has voiced concern. David Harsila, president of the Alaska Independent Fisherman’s Marketing Association, said that he and his organization have “found that mining is an inherent problem with the environment and the salmon.” Harsila described the salmon in Bristol Bay as “very sensitive,” and he believes that if the Pebble Mine is created, “the salmon will be affected in a very big way . . . It really looks bad from our point of view.”

According to Ann Rappaport, a field supervisor with the Anchorage Fish and Wildlife Office, and Phil Brna, a fish and wildlife biologist with Fish and Wildlife Services (FWS), the increased presence of exposed metals in waterways as well as of other chemicals associated with mining (such as acid mine drainage, mercury, arsenic and cyanide) can kill off salmon populations. “Some of these metals are so toxic they can kill fish,” Brna said. Ultimately, with the presence of metals and chemicals the entire watershed faces destruction.

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

Jeff Courier, borough manager with the Lake and Peninsula Borough (the government of the Bristol Bay area), said Bristol Bay would see a direct economic gain from the mine as the state has a severance tax attached to the extraction of natural resources such as the ore in the Pebble Mine project. As to how much revenue would be generated, Courier said that the proposal has the potential to be quite profitable though it’s like “trying to nail a chunk of J-E-L-L-O to the wall” – describing the uncertainty that accompanies mining and profits.

The fear for many is that if the salmon goes, so goes the industry of the area. “Salmon has been the only economic driver in Bristol Bay for decades . . . You have to realize that,” Courier said. The borough notes that “the majority of borough residents rely upon commercial fishing as a primary source of cash income.” And just as the economy and tribal lifestyle is tied to the salmon, so is the sustainability of the area’s tourism – a cash crop that is incredibly lucrative.

For Danny Constantine of Renewable Resources, a former employee of the Department of the Interior (DOI), the mining project isn’t just about fish. It’s about what is tied to the salmon industry: tourism. “Tourists aren’t coming here to look at an open-pit mine,” Constantine said. “They’re coming to fish.”

Tourism is second only to salmon, though they are inexplicably interrelated: “Tourism and recreational activities are the second-most important industries in the borough, and are rapidly increasing in economic importance,” according to borough representatives.

Joe Donovan, a mining expert who has worked in British Columbia with mines and who currently serves as a West Virginia University (WVU) professor of geology as well as a director of the National Mine Lands Reclamation Center (NMRLC), said: “The concerns are real. With any form of mining comes some impact to the land that surrounds it. Once the mine goes into operation, the land will never be the same. The holes dug from mining and the rocks removed leave the earth altered forever.”

The Uncertain Pebble Project

Mike Smith, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and permitting manager for Northern Dynasty (the company behind the Pebble Mine project), defined the mine’s progress as being in the “very early stage.” In 2001 Northern Dynasty Mines Inc., a Canadian company, purchased the mineral rights to state, public lands for what is believed to be the largest gold and copper ore deposit in the world. To obtain mineral rights in Alaska, a company participates in an overly simplistic process that begins with the staking of a claim by placing four posts in the ground at the four corners of the mineral site, said Dick Mylius, director of the Division of Mining Land and Water in the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

After the land has been claimed, the company pays a fee on a per-acre basis; mineral rights are rented in allotments of 40 acres for $25 a year or 160 acres for $100 a year. Mylius said that Pebble purchased the mineral rights to tens of thousands of acres of land in the area. And, without explanation, representatives from the Alaska DNR stated that in Alaska, Canadians have the right to purchase American mineral rights.

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

It is that easy. An ecosystem can be potentially destroyed for as little as $100 a year for every 160 acres. This small cost for a large mining agency turns into a huge cost for the tribes and wildlife in the area. Although no plan is concrete, Sean Magee, spokesperson for Northern Dynasty, said that two potential drilling/mining sites exist in the Bristol Bay tributaries. These sites would directly impact between 13 and 15 square miles. Pebble West would be an “open-pit” mine, while Pebble East would require more rigorous mining techniques. “Projects of this scale will certainly have effects on the environment,” said Magee.

Brna explained that the mere presence of a mine – from its inception – will automatically directly impact the area by adding a mine where nature now exists. Moreover, small changes that could occur because of mine placement, such as an increase in water temperature, can destroy ecosystems – a concern that has led many in opposition to ask “Is it worth it?” Brna said, “If you change these temperatures by one or two degrees, you change the fish’s ability to survive.”

Current estimates from Northern Dynasty show that if the mine makes it past the permit stage, more than 2,000 construction jobs, lasting between two and a half to three years, and 1,000 operating jobs, lasting the mine’s lifetime (speculated to be between 50 and 100 years) will be created. The local tribes and Alaskans will be granted the jobs, while a small tax will be placed upon the extraction of the minerals taken out by the Canadian company. While the area could use some economic gains, Hobson of the Nondalton tribe believes that the creation of the mine is a short-term fix for the area’s economy and a long-term assault on the ecosystem.

“It would help the area economically,” Hobson said. “But it’s a high risk for a short-term gain. We’ll spend the rest of the years trying to clean that place up.” Specifically, Hobson is concerned about cyanide being used to extract minerals from rock. According to Professor Donovan, cyanide in large concentrations is toxic to wildlife. Although Magee explained that Northern Dynasty is unsure if such practices will be used in the Pebble Project, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has stated that cyanide is commonplace in gold mining – specifically in Alaska.

In addition, a new road system that is planned to be more than 100 miles long leading up to the mine will kill some surrounding vegetation. And vegetation that is not killed will have higher levels of metals in plants that humans eat, Brna and Rappaport explained. And far beneath the deepest of mine shafts and drilling sites, beneath the gold and the copper, lie fault lines, area biologists said. “What if an earthquake strikes and cyanide contaminates the watershed?” they wonder.

“There’s going to be a loss of fish and wildlife,” Brna said. “That’s the trade-off for economic development . . . are we willing to accept that loss for gold and copper?”

“This is one of our last great chances to do it right – to manage wisely a habitat and a sustainable fishery, factoring in the needs of all species reliant on the renewable bounty of one of earth’s most magnificent geographic regions. There is something else at stake here – the rights of future generations to know, experience and benefit from these great lands and waters. With the tools of knowledge, financial resources and inspired engagement, we at the ACF believe that this heritage can and should be passed along substantially undiminished. This is one of our nation’s greatest stewardship challenges and opportunities,” said Deborah Williams, executive director, Alaska Conservation Foundation.1

© Robert Glenn Ketchum

1 The photos and certain sections of this feature were taken directly from Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery. Photographs by Robert Glenn Ketchum. Essay by Bruce Hampton. Copyright © 2001 by Aperture Foundation, Inc. Click here to order a copy of this enlightening book with breathtakingly beautiful photography. Click here for more Robert Glenn Ketchum photos.