Kivalina & Climate Change: Innovative Solutions from Israel

This urgent call to address severe erosion challenges facing the isolated Alaskan community of Kivalina was made by then Colonel Kevin Wilson, Commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Alaska District. (See livebetter Issue No. 4, 2008, Coastal Erosion and the Threat to Kivalina, Alaska.) Wilson’s comments drew upon a 2006 USACE assessment of Alaskan communities endangered by climate change. More recent studies1 have only confirmed the need for decisive action either to implement more comprehensive but temporary engineering measures to protect the village or to devise a state-wide strategy for effective relocation.

Ironically, effective efforts to assist Kivalina in its time of need are coming from Nisan Almog and Alon Schwabe. These two artists from Israel have adopted the community’s cause as part of the non-profit ReLocate Project. As such, they are working with community members, the Alaskan Design Forum and other socially engaged artists from around the world to initiate a “new, community-led and culturally specific relocation.” This inclusive effort embodies new paradigms more attuned to a value-based assessment of communities under threat while implementing practical projects to address core concerns and to improve the lives of people threatened by climate change. As such, Almog and Schwabe are following in a long line of innovation, which began in 1948 when the little “start-up” nation of Israel first began developing innovative solutions to some of the world’s most pressing humanitarian problems.

Kivalina & Coastal Erosion

With every minute that passes, the remote Alaskan village of Kivalina, which is situated approximately 600 miles northwest of Anchorage, edges closer to disappearing completely. Sitting on a peninsula exposed to the full force of the Pacific Ocean, the village faces the threat of imminent relocation due to rising sea levels caused by climate change. Kivalina is an isolated village that was permanently settled in 1953 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It consists of about 400 inhabitants; most are members of the Inupiat Tribe – an endangered remnant of a unique culture.

Photo Credit: AK Div. of Commerce

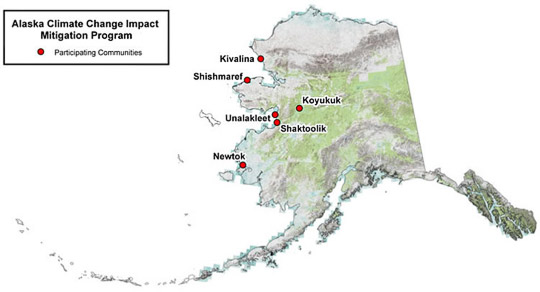

Today, the community’s environmental challenges continue unabated with “rapid coastal and riverbank erosion and flooding that threaten both infrastructure stability and human well-being,”2 according to Rachael Peterson, former research assistant at the Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University. Peterson noted in her article, “The Difficulty Relocating Climate-Affected Communities,” that the naturally occurring principle drivers of coastal erosion – multiple meteorological and geological processes like severe storms, sea ice melt and permafrost thaw – are intensified by climate change and “occurring at a speed never before observed in the instrumental record. A 2009 study found that coastal erosion has more than doubled – up to 45 feet per year – in a five-year period between 2002 and 2007 along a 40-mile stretch of the Beaufort Sea.” In fact, a 2006 USACE assessment “estimated that the villages of Kivalina, Newtok and Shishmaref have 10 to 15 years before their current locations are lost to erosion.”

As yet, no sustainable solution for prolonging the lifespan of Kivalina has been identified. Nor has any solution been found to move it to safe ground as part of a managed retreat strategy. Any proposal has to mitigate division of responsibility for coastal erosion programs in Alaska. USACE construction of barriers, which includes thousands of heavy sandbags, is a temporary measure which, according to Wilson, only buys Kivalina enough time to get through the next storm. Then Brigadier General John Peabody, Commander and Division Engineer, USACE Pacific Ocean Division, asserted in the aforementioned livebetter article that the fundamental challenge is “no federal mechanism or other reliable resource capability exists to provide a response appropriate for the magnitude of the problem.” USACE has been able to utilise Congressional funds towards hard engineering solutions for Kivalina, such as rip rap rock revetment – large rocks weighing several tons. These can dissipate wave energy, but, according to Wilson, they can only last 15 to 20 years.

Current Dilemmas

As Peterson observes when citing the latest General Accounting Office (GAO) report, “There is no single federal agency responsible for managing and funding flooding and erosion programs in Alaska.” Responsibility is divided between multiple agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), USACE, Denali Commission and the Immediate Action Workgroup of the Governor’s Sub-Cabinet on Climate Change. Peterson’s research is the most comprehensive relative to the precise responsibilities of each agency and their capacity to contribute. Therefore, it is worth repeating a few of her findings below.

In 1998, the Denali Commission, an independent federal agency, was created to provide support to Alaska’s remote communities, for example, by allocating grant funds for relocation planning like that of Newtok, another threatened Native village. However, it is not responsible for flooding and erosion programs. And, allocation of FEMA resources is contingent upon a number of variables. John Madden, director of the Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services, commented that FEMA can only operate in cases of “immediate disasters and not imminent threats.”3 Therefore, use of federal funds for such purposes is inherently reactive. FEMA is also restricted by other qualifying factors like “approved disaster mitigation plans,” an official declaration of a federal disaster and a “cost-effective” funding requirement.

Photo Credit: Denali Commission | HESCO Seawall and Kivalina fuel tank farm.

Since many FEMA programs require some kind of state or applicant cost-sharing arrangement, small Alaskan villages are unable to afford such services. Additionally, FEMA’s hazard mitigation statutes are defined by the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (1988), which provides two further obstacles to a sustainable strategy for threatened communities.4 First, funds are only allocated for post-disaster relief in order to restore the affected area back to its pre-disaster state. Funds are based on the magnitude of the disaster and cannot be used for permanent relocation. Second, as previously stated, funds are contingent upon an official declaration of emergency. Hence, Alaska Governor Sean Parnell acted swiftly to declare a disaster in Kivalina on Sept. 7, 2012, after water holding tanks were damaged by high water. This process assured money would be available for emergency protective measures and immediate restoration efforts.5

Looking ahead, and in light of the required declaration of a disaster to release federal funds, Peterson writes that communities would benefit from “coordinated state and federal relocation efforts” and an anticipatory mechanism to address threats that are gradual, such as climate change. She explains: “Newtok, . . . hailed as the most advanced in its relocation efforts, relied largely on its own village leadership . . . to locate and secure an acceptable relocation site. Not all villages can rely on such dynamic internal decision-makers to lead this process.”

Madden indicated that one progressive measure would be to insert more qualitative concepts of the social, environmental, cultural and non-monetary costs of erosion, which explicitly surpasses the reductive “cost-benefit analysis” doctrine.

New Paradigms in Action

Enter Israel’s Almog and Schwabe. Almog, an urbanist and social entrepreneur, is an expert on participatory spatial planning practices, and Schwabe focuses on civic artistic action for empowerment of local inhabitants. Both participated in the Next North symposium, held September 2012 at the Anchorage Museum in the Rasmuson Center, thus witnessing first-hand the plight of Kivalina and the state of the community during the disaster declaration.

hoto Credit: Denali Commission | Working on the top layer of HESCO seawall in Kivalina.

According to Almog and Schwabe, their work in Kivalina is “part of a series of previous attempts to assist the community in the relocation process. For numerous reasons, previous relocation efforts have failed and left the community looking for alternatives. As time passes by and a governmental relocation process seems to have no feasible future, there seems to be room for creative ideas and new methodologies for public discussion regarding the relocation issues that have emerged. ReLocate is a group of social artists from around the world working with a group of delegates from Kivalina to initiate a new, community-led and culturally specific relocation.”

To this end, the WochenKlausur Artist Collective, a ReLocate participant, undertook extensive research during an on-site visit to Kivalina in August 2012. They focused on a number of problems and challenges that people in Kivalina are dealing with on a daily basis due to the village’s remote location and lack of resources. WochenKlausur invited “Agents of Change” – individuals, organisations and associations in the United States and worldwide – to team up with people from Kivalina to solve specific challenges.

According to Almog and Schwabe, the ReLocate project defined a list of short-term, immediate issues to be addressed in Kivalina’s current location before planning for relocation. Created in dialogue and collaboration with Kivalina residents, the research targets problems more precisely and reflects the immediate and long-term needs of the residents. Results were shared and discussed with both Kivalina delegates and state agencies in order to create a call for action that will engage both local and state agencies in the village relocation process.

Longer term, the ReLocate project intends to make relocation-related social, political and environmental issues visible to global audiences; to support community discussion and consensus building and to locate, connect and educate new relocation partners. The Project also plans to create spaces where Kivalina residents can share original media and ideas about local identities and ways of life, and to develop an infrastructure for managing global support and for pursuing relocation planning opportunities.

Almog and Schwabe stress that Kivalina’s case is special, which is why emphasis has been placed on the community’s characteristics and specific issues. The Israeli artists comment: “Our task was not to come and ‘save’ the village as we don’t like to refer to our project in terms of gain and loss. ReLocate aims to suggest an alternative to the current conditions and operations taking place in Kivalina in a process that allows residents to lead and navigate a relocation plan. Though immediate problems, such as no running water or toilet systems and no planning or access to higher education, may be similar in other native communities, each community is dealing with a set of specific conditions.”

For instance, the potential installation of an Israeli-invented toilet, which needs no water and leaves no waste (and that won funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), could address Kivalina’s existing water and sanitation challenges.6 Notwithstanding this measure, the project can be an inspiration and source of knowledge for other communities facing similar conditions. The methodology employs an artistic approach to challenge the current order while bringing together different governmental, social and environmental agencies to act together. Since this process offers a new model for civic engagement and participation, it can only be effective when all parties are responsible and engage together.

Photo Credit: Denali Commission | Supersacks on the damaged seawall in Kivalina.

Unfortunately, as previously mentioned, the only way for Kivalina to receive federal help now is through complex, bureaucratic procedures for disaster declaration. Such declarations lead to a state of emergency that forces communities to forfeit control over their sovereignty in order to bring an end to their predicament. In this cycle, endangered communities find themselves hanging between disaster and emergency, where no opportunity exists for a progressive, lasting and prosperous future. Therefore, it is important to create long lasting procedures that will involve indigenous communities in decision making and planning towards a just and sustainable future. As long as this paradigm shift takes place, the question of who takes a leading role is less important – whether it be artists, city planners, regulators or state clerks – explains Almog and Schwabe.

A Start-Up Nation’s7 Innovative Solutions

The problems that Kivalina faces are not unique. As Peterson observes, “Scientists have predicted that 180 U.S. cities are vulnerable to a one meter sea-level rise” while “the United Nations (UN) reports that 44 percent of the world’s population lives within 150 km of the coast.” This means more than three billion people will inevitably be affected by near-term climate change trends predicted by scientific experts.

The ReLocate project offers one possible, cooperative model to tackle climate change challenges both at the local and national level. This flexible approach to problem solving and disaster preparedness comes naturally to Almog and Schwabe as Israel is one of the world’s leaders in providing innovative solutions to widespread challenges. According to Dan Senor and Saul Singer, authors of Start-Up Nation, “Since their country’s founding, Israelis have been keenly aware that the future – both near and distant – is always in question. Every moment has strategic importance.”8

This forward-looking approach was embedded in Israel’s policies for international humanitarian efforts a decade after its birth. According to MASHAV, Israel’s Agency for International Development, “In 1958, the State of Israel adopted an official humanitarian aid agenda as a principal element of the country’s international cooperation efforts. Nowadays, Israel is often called upon to dispatch aid in the wake of earthquakes, floods, famine and other natural disasters.” These efforts, as well as long-term projects for sustainable development around the world, are coordinated by MASHAV. And the organisation’s multilateral initiatives have benefits for other pressing global challenges besides climate change.

On April 18, 2012, Ambassador Daniel Carmon, head of MASHAV, and Rajiv Shah, MD, Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in Washington, D.C., to enhance bilateral cooperation on food security focusing initially on Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. At the signing ceremony, Shah said the United States recognizes Israel’s achievements in specific areas of increasing value to some of USAID’s top priorities in combating poverty and hunger. This was especially true for Israel’s expertise in water conservation, dry land management and the ability to turn arid lands into highly productive farms. Therefore, the two agencies have plans to work together on issues, which include empowering women, capacity building, nutrition and climate change.9

At the governmental policy level, Israel offers many templates for implementing a more creative and sustainable approach to climate change for isolated or under-represented communities involving multiple actors in a democratised decision-making process. On Dec. 7, 2012, the UN voted to adopt an Israeli-sponsored resolution on “Entrepreneurship for Development,” which would, according to Carmon, remove bureaucratic impediments to development, open up economic opportunities and foster responsibility in both local entrepreneurs and donor countries.10 A few days after the UN passed the Israeli-led resolution, Carmon signed a MOU with the Canadian International Development Agency, thus strengthening ties that will enable like-minded countries to collaborate and share expertise to implement lasting innovations that address current and future challenges.

Photo courtesy of MASHAV, Israel’s Agency for International Development

MASHAV demonstrates that governments can be as creative as intrepid artists in effecting sustainable change. Indeed, one MASHAV international workshop planned for March 2013 will focus on “Media Strategies for Social Change,” thus echoing ReLocate Project methods. In late 2012, the Agency also hosted a course on “Agriculture and Environment in a Changing Climate,” which paves the way for more proactive plans for small communities, many of whom have relied traditionally on subsistence agriculture to thrive as they adapt to new realities.11

These initiatives – combining governmental action and expertise with local actors – offer a way forward to address climate change challenges. They also engage directly with an issue of international importance as climate change challenges humanity to think more critically about how it will interact with its environment as more communities around the world, not only those in remote Alaskan areas, face the threat of relocation and loss of their unique way of life.