Uncontacted Tribes By Choice or By Chance?

Indigenous peoples in a remote Amazon rainforest area near the Peruvian-Brazilian border were photographed for the first time in May 2008 by Gleison Miranda, who was in a small plane flying overhead along with Jose Carlos dos Reis Meirelles. Painted bright red, the tribal people appeared visibly upset. Probably thinking the plane was a huge bird and fearing for their safety, they armed themselves with bows and arrows, their most fatal weapon.

© Photograph: Gleison Miranda / FUNAI

Other than a few anthropologists, the public was unaware of the tribe’s existence because they lived “uncontacted” from the outside world. Reis Meirelles, an anthropologist from FUNAI, the Brazilian government’s Indian Affairs Department, had Miranda take the pictures “to show their houses, to show they exist.” He wanted to highlight a monumental crime against the tribes, nature and the world: every year 28,000 hectares (around 69,200 acres) of the Amazon Forest is destroyed by “civilized” developers.

“Uncontated tribes” are groups of people who, either by choice or by chance, live without contact or considerable interaction with modern civilization, explains Beatriz Huertas, an anthropologist from CIPIACI (Association for the Protection of Uncontacted Tribes). Jonathan Mazower, an anthropologist from Survival International, a passionate advocacy group supporting tribal people worldwide, believes there are about 100 uncontacted tribes that they know about. Although uncontacted tribes exist worldwide, most are located in the Amazon rainforest, especially in Brazil. Commenting on the photographed tribe, Mazower agrees that they were likely afraid and sending a message to go away and leave them alone.

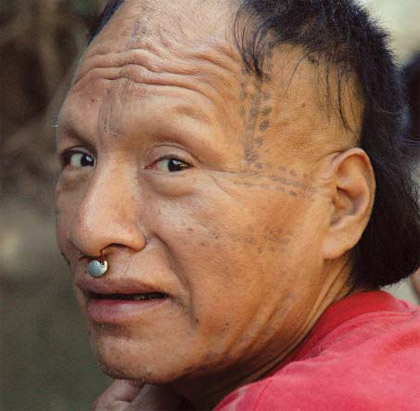

The Scars of Contact

© Photograph: Gleison Miranda / FUNAI

A history of violence, abuse, slavery, death and genocide has shown these tribes how cruel and harmful the outside world can be. Mazower explains: “Mostly these people, especially the ones in South America, are the descendents of Indian tribes who experienced massacres and atrocities a hundred or more years ago. This principally occurred during the Amazonian ‘rubber boom.’ Europeans set up companies and exploited the Indians for slave labor to gather wild rubber. The tribes were devastated, and around 90 percent of their population were killed as a result of the violence and newly introduced diseases. Many of the Indians survived only by retreating into the remotest part of the jungle – the rivers’ headwaters. Today’s uncontacted Amazonian tribes are often these survivors’ descendants. Thus, their collective memory tells them that outside society is dangerous and should be avoided.”

“The Massacre of the 11th Parallel,” a 1963 Brazilian incident, is recounted by Survival International as being a truly infamous case of genocide against the Cinta Larga (long belts) tribe. According to records, Antonio Mascarenhas Junqueira, owner of the Brazilian rubber company Arruda, Junqueira & Co., hired a small plane from which he dropped sticks of dynamite directly into the Cinta Larga village below. More murderers followed on foot to finish the devastating attack. Finding a woman breastfeeding her child, they shot the baby’s head off and then hung the mother upside down and sliced her in half. Mascarenhas Junqueira planned the massacre because, allegedly, the Cinta Larga Indians were interfering with his commercial activities. Before committing one of the world’s worst cases of cruelty against indigenous peoples, the rubber company owner declared: “These Indians are parasites, and they’re shameful. It’s time to finish them off; it’s time to eliminate these pests . . . .”

© Photograph: Survival

Given experiences like this, it’s clear why many uncontacted tribes have a collective memory filled with repulsion related to the outside world. Indeed, Huertas has asked previously uncontacted tribes why they’re so afraid and was told that their ancestors had shared their horrific experiences with younger generations. Peru’s tribes had similar experiences during the rubber boom. Huertas explains: “Barbarian rubber workers invaded the indigenous peoples’ territories on the river banks and killed hundreds of them. After this attack the Peruvian tribes resolved to live isolated. They don’t live in the Neolithic era; they know what the outside world is like. They’re experienced in the tragedies that contact with ‘civilization’ can bring.”

Tribes have also been victimized by violent incidents unrelated to the rubber boom. For example, the Ayoreos’ tribe suffered during the Paraguayan government’s 1942-1989 dictatorship. Augusto Fogel, director of Paraguay’s INDI (Indigenous Institute) recounts one such incident: “One day a soldier came from the forest with an Ayoreo’s head in his hand. After this gruesome incident, activists asked the government to create laws protecting indigenous peoples. Alfredo Stroessner, Paraguay’s then-dictator, posted signs in the forest to say ‘It is not allowed to hunt Ayoreos.’ This was like saying ‘It is not allowed to hunt tigers.’ That was the last straw.”

© Photograph: Survival

The tribes’ disastrous experiences at the hands of “civilized” outsiders are not just relegated to those with economic or political means and motives. Christian religious fervor has been and continues to be a destructive force for many of South America’s uncontacted and remote tribes. Just 24 years ago, a U.S. Fundamentalist church sent missionaries to the southern part of the Chaco in northern Paraguay, where they destroyed the Ayoreos’ quiet and centuries-old way of life. The missionaries thought the Ayoreos needed to be “civilized.” Fogel elaborates that “. . . as a consequence of the contact, many Ayoreos died due to disease, and others no longer wanted to live. It was a disastrous experience, which led the Paraguayan government to take action to protect them.” Unfortunately, such incidents continue today.

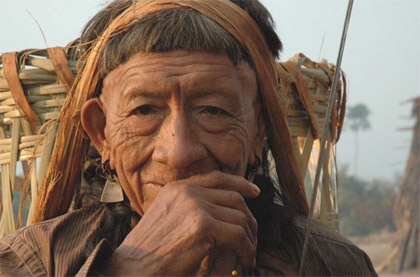

A System of Life

Mazower summarizes these remote tribes’ daily life: “Usually indigenous people are hunter-gatherers. Additionally, they likely have small gardens around their village where they grow vegetables and fruits. They also might fish. Thus, they have a very healthy diet. As long as their territory remains safe, they can live very well.” Huertas adds, “They subsist on wild plants and ‘bush’ meat, such as monkeys, deer, tapirs, turtles, fish, bananas and nuts.” Because they don’t use canoes, the tribes live away from the river during the rainy season. However, during dry seasons, they live on river banks, where they fish and look for turtles’ eggs, which are important protein sources. Due to their seasonal living habits, they usually live in nomadic groups or families. But, because of their isolation and migratory behavior, it’s hard to keep track of each group’s total number. Huertas clarifies, “We don’t know how many people are members of each tribe; there could be 20 or 2,000. Also, because of death, the number of members changes constantly.”

These tribes have been living in the forests for hundreds to thousands of years, depending upon whether they’ve been contacted or not. “These tribes all have their own languages but, depending on how contacted they are, they may also speak Portuguese, Guarani or Spanish,” explains Mazower.

Because of deforestation and bushmeat consumption, some individuals have been critical of indigenous peoples’ treatment of the environment. However, others believe they have been accumulating important knowledge and traditions that allow them to work harmoniously with nature rather than destroy it. Huertas says that “uncontacted tribes keep and pass along their knowledge in a way no one else does – knowledge about preserving resources and nature.”

However, Mazower adds: “There’s also a slight danger when outsiders romanticize the Indians and see their value only in terms of them protecting the environment better than anyone else. As a result, others think the tribes have a peaceful life . . . .” Although living happily surrounded by a calm forest is how most people picture uncontacted tribes, the “peaceful forest” is now only a distant memory for most indigenous peoples thanks to rising threats, particularly within the past few decades.

Outside Threats

© Photograph: Joaó Ripper/Survival

“Civilized” groups have been attempting contact with remote tribes for decades. Loggers, cattle ranchers, oil companies and sometimes even governments invade their territory, primarily for land and resources. Mazower explains that tribes are usually contacted because people desire their land or its resources. As a result, indigenous peoples have been forced from their property and have continued to run deeper into the forests, but now there’s nowhere left to run to. Fogel says that cattle ranchers and loggers are responsible for putting the tribes’ habitats in danger.

Mazower elaborates: “It’s very similar around the world. For example, in Paraguay there are problems with cattle ranchers – big Paraguayan and Brazilian companies – who are buying up the Indians’ land. They’re clearing the forests by burning it. Because of the incursions of big bulldozers, the Indians are always running and leaving their land.”

Huertas agrees: “The expansion of the dominant society over them is one of the biggest threats to uncontacted tribes. They try to protect their land because land is the source of their food and everything they live off.”

However, Mazower believes the largest threat is disease. He adds: “The most serious threat to the Indians is the introduction of western diseases, which they have never experienced before and, resultantly, have no antibodies for. Therefore, many times these can be fatal to entire tribes.” Huertas says that even a simple cold can kill all tribal members, and no one is ready to confront the situation.

Death from “Progress”

In 2007 Survival International published a report titled “Progress Can Kill,” which discusses how imposed development has been destroying uncontacted tribes. The report begins with a quote from a Malaysian tribal member: “Outsiders who come here always claim they’re bringing progress. But all they bring are empty promises. What we’re really struggling for is our land. Above all else that is what we need.”

© Photograph: Fiona Watson / Survival

Survival International states that 90 percent of tribes in both North and South America died mostly from disease following contact with Europeans. The mortality rates after outside contact provide evidence of the damage caused to each tribe. As an example, the Great Andamanese, a previously uncontacted tribe who lived on their own land for around 60,000 years, were relocated to a new “home” by the British with the purpose of providing them a “better life.” As a direct consequence, 99 percent of their population died, which resulted in their numbers decreasing from about 5,000 to a mere 53 today. Of 150 babies born, all died before their third birthday. In fact, Survival International states that indigenous peoples, such as Aborigines, live 10 years longer on their own lands.

In addition, many tribal members are not prepared physically, mentally and/or psychologically for an abrupt transition to western society. Huertas explains: “Demoralization is something very common as a result of contacting those tribes. Contact is a shock for them because the outside world is something they’re unable to process. It’s very traumatic for them to see many of their group members dying; this always leads to feelings of demoralization and deep depression. However, the psychological impact is something that no one ever talks about.” For example, between 1985 and 2000 more than 300 Guarani-Kaiowa committed suicide with the youngest only 9 years old, reports Survival International.

Sexually transmitted diseases are also an often unspoken but very real threat to remote tribes. After contact most tribes suffer from such diseases. Indeed, in 1971 Brazilian government efforts to establish “friendly contact” with the Parakana caused these isolated Indians to become infected with gonorrhea. In this example, outsiders brought gonorrhea to the Parakana, who had never experienced a sexually transmitted disease, and 35 women became infected. In addition, many tribal women were sexually abused and prostituted with some of their children resultantly born blind, affirms Survival International.

When indigenous peoples are contacted and their lands lost, dietary changes can also become life-threatening. A vivid example is the Guarani tribe, who predate the establishment of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay; they continue to lose 10 percent of their land every year. In 2006, 20 Guarani children died from starvation in just three months. But insufficient food is not the only diet-related health impact. According to Survival International, in Australia 64 percent of urban Aborigines suffer from obesity. After being used to a different way of life and diet, the “civilized” lifestyle forced upon them requires less energy output in addition to the consumption of an unhealthy diet, leading to western diseases such as obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease.

Where is the law?

© Photograph: Fiona Watson / Survival

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, approved Dec. 10, 1948, by the United Nations (U.N.), states in Article 1 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. . . .” Article 2 continues “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration without any distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion. . . .”

Additionally, the U.N.’s “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” affirms “that indigenous peoples are equal in dignity and rights to all other peoples while recognizing the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such . . . .” Article 10 adds: “Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories. No relocation shall take place without the free and informed consent of the indigenous peoples concerned and after agreement on just and fair compensation and, where possible, with the option of return.”

Both these international laws have enough declaration to protect tribal people; however, to be effective, the laws need to be recognized and enforced. Mazower summarizes the problem: “There is U.N. declaration on indigenous peoples, but a U.N. declaration is not something that has any legal power. It’s just a general statement by the General Assembly. It has no legal force.”

The only international law specifically created for tribal people was written by the International Labour Organization (ILO), a global group founded in 1919 to promote worldwide social justice and to recognize human and labour rights. ILO 169 was brought into existence to protect the 350 million indigenous peoples from marginalization in almost every aspect of daily life. So far 20 countries have ratified this international treaty.

© Photograph: Survival

From the beginning of time, indigenous peoples have been living with nature and in nature while developing nations have exploited and abused it. For example, many indigenous and subsistence peoples have relied on what is now known as “sustainable forestry” for their survival and sustenance while outsiders have been and continue to be responsible for the wholesale destruction of forests mostly for economic gain. This insatiable greed and uncontrolled use of the world’s natural resources are already causing damage to all life on Earth. Uncontacted tribes are collateral damage within this path of destruction. When coupled with intolerance, disrespect and social injustice, uncontacted and remote tribes just might be the world’s best example of man’s inhumanity to man – a horrid continuation of North American Indian history. Unfortunately, tribes don’t have the power to hold these “civilized” people accountable. And, all too often, the rest of the world just doesn’t care.