BP’s Deepwater Horizon America’s Haunting Catastrophe

On April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico and became the world’s largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. Methane gas, under extreme pressure, escaped from the well and shot up the drill column causing an explosion that engulfed the platform in fire. Despite multiple efforts to douse the flames, the platform, weighing 58,000 tons, sank one mile to the ocean floor on April 22, 2010. Eleven crewmen died, and 17 others were injured.

The Deepwater Horizon platform, owned by Transocean, was under lease to British Petroleum (BP), which was drilling an exploratory well at a depth of 5,000 feet in the Macondo Prospect, about 40 miles off the coast of Louisiana. Over the course of the next three months, the well released approximately 4.9 million barrels of crude oil (205.8 million gallons) – more than 60,000 barrels per day. By comparison, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which occurred in Prince William Sound, Alaska, on March 24, 1989, was estimated at 260,000 barrels. For further perspective, consider that the United States consumes more than 20 million barrels of oil per day, which means the entire BP spill comprised slightly less than one-fourth of one day’s petroleum usage by Americans.

After a number of unsuccessful efforts, the gushing Deepwater Horizon wellhead was eventually capped on July 15, 2010. By September 15, 2010, BP had effectively pumped cement into a relief well that intersected the blown-out well and plugged the BP-operated Macondo Prospect permanently. One-third of all oil production in the United States comes from 3,500 such platforms in the Gulf of Mexico.

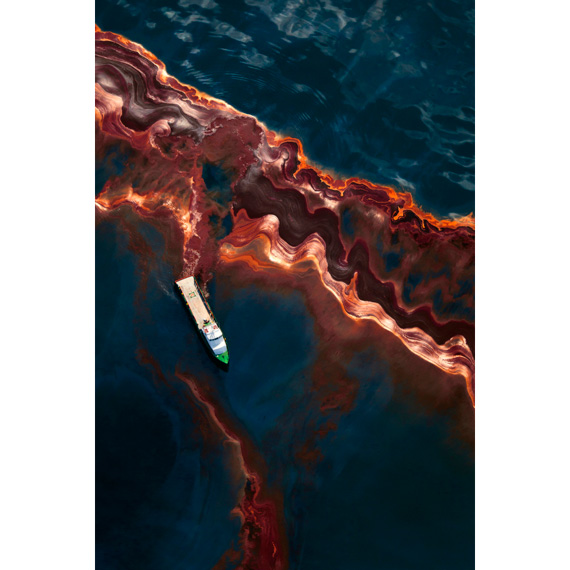

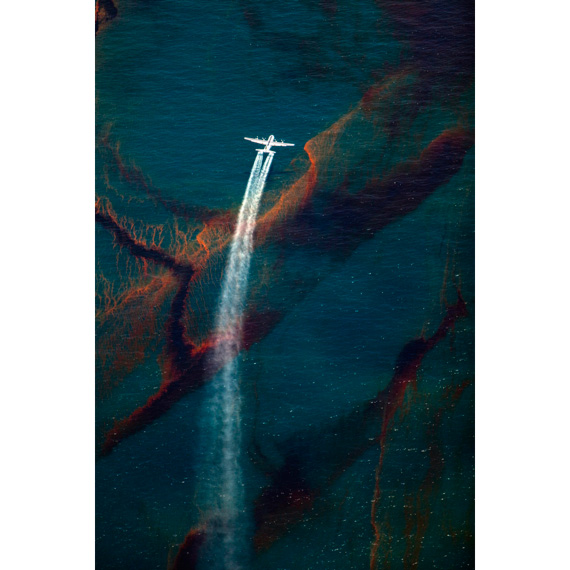

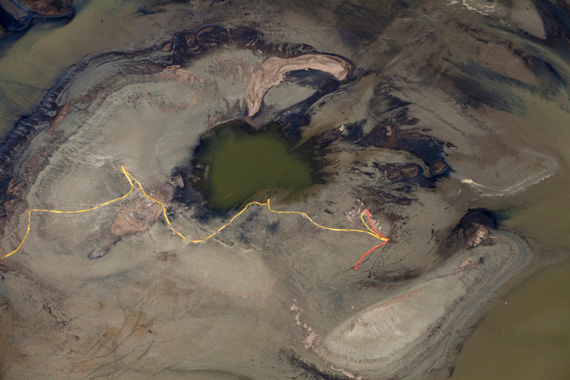

The devastation to the Gulf Coast and the resulting consequences are still unknown. In all, 632 miles of coastline were affected and show lingering signs of damage. The oil’s presence continues to spread and to thicken on the ocean floor – radiating far and wide from the wellhead site. While many strategies were used in the clean-up effort (8 million feet of absorbent boom, 3 million feet of containment boom, building sand berms, plus skimming and collecting the oil for processing later), the most visibly altering were the use of surface-controlled burns and the application of Corexit.

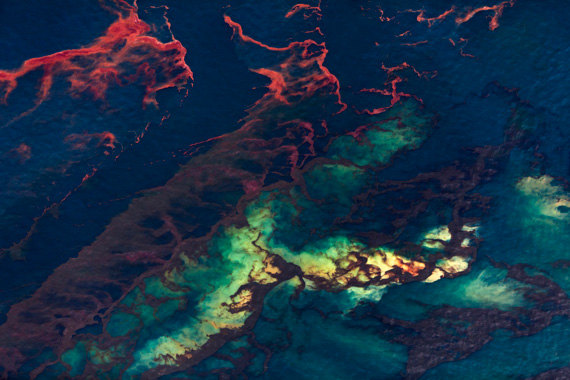

Corexit, a toxic chemical dispersant used to accelerate the degradation process, was heavily used both above and below the surface. On May 1, 2010, planes began flying over the spill site spreading up to 25,000 gallons per day across the ocean surface. At the same time, the chemical dispersant was being sprayed at the wellhead five thousand feet below the sea. While this tactic had never been tried, it was thought mixing dispersant with oil would keep some of the oil below the surface, thus allowing microbes to digest the oil before it reached the surface. However, deepwater plumes of dissolved oil and gas were soon found. One was as large as 10 miles long (16km), three miles wide (4.8km), 300 feet (91m) thick in spots and persisting for months at a time. In all, 1.8 million gallons of Corexit were used under water despite the risks inherent to the product.

Corexit, a toxic chemical dispersant used to accelerate the degradation process, was heavily used both above and below the surface. On May 1, 2010, planes began flying over the spill site spreading up to 25,000 gallons per day across the ocean surface. At the same time, the chemical dispersant was being sprayed at the wellhead five thousand feet below the sea. While this tactic had never been tried, it was thought mixing dispersant with oil would keep some of the oil below the surface, thus allowing microbes to digest the oil before it reached the surface. However, deepwater plumes of dissolved oil and gas were soon found. One was as large as 10 miles long (16km), three miles wide (4.8km), 300 feet (91m) thick in spots and persisting for months at a time. In all, 1.8 million gallons of Corexit were used under water despite the risks inherent to the product.

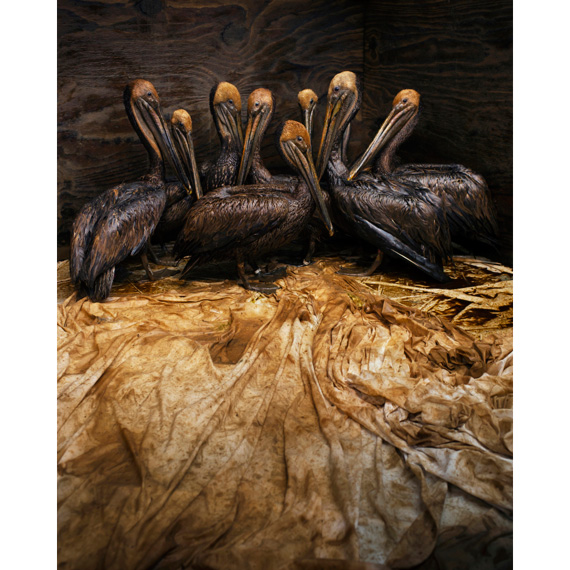

Southern Louisiana has about 40 percent of the nation’s coastal wetlands. These wetlands provide a range of benefits, including flood control, water purification, storm buffer, wildlife habitat and nursery grounds for aquatic life. Oil has the potential to persist in the environment and cause long-term effects on fish and wildlife. As of November 2, 2010, 6,814 dead animals had been collected, which includes 6,104 birds, 609 sea turtles, 100 dolphins and other mammals. Since January 1, 2011, more than 200 dead dolphins have been found in the affected area, with half of them stillborn or newborn infants. Tar balls found in shrimpers’ nets November 2010 prompted a five-month closure of 4,200 square miles of the Gulf from shrimping. This created a tangible effect on the dinner tables of many Americans beyond Louisiana because nearly one-third of the United States’ shrimp and oyster harvest comes from the Gulf coast.

Though nearly a year has passed since the wellhead was capped, scientists have determined that up to 75 percent of the oil from BP’s disaster still remains in the Gulf environment. Much of that oil remains under the surface invisible to the eye, thus becoming a forgotten, hidden ghost of an environmental catastrophe, haunting us of our dependence on oil.

Daniel Beltrá

Daniel Beltrá, born in Madrid, Spain, is a conservation photographer based in Seattle, Washington. He witnessed first-hand the devastation that almost five million barrels of oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill wreaked on the Gulf of Mexico.

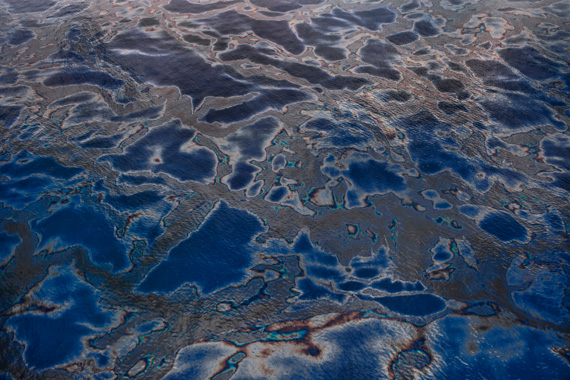

Flying in a Cessna floatplane at altitudes more than 3,000 feet – pointing his camera out the window – Beltrá logged 40 hours in little more than two months while photographing the BP spill in the Gulf. “Up in the air you see the magnitude of the damage. The extent was so vast, it’s like trying to clean an Olympic pool full of oil while sitting on the side using Q-tips,” he comments.

For the photographs, Beltrá minimized his body contact with the aircraft because the vibrations could ruin the perfect shot. To enhance the view of oil beneath the Gulf surface, he also used a polarizer filter to eliminate glare and reflections created by the sun. In some of his photographs, the water surface is patterned with entrails of blue and orange, the result of the massive quantity of chemicals being pumped below the surface.

Beltrá isn’t depressed by the destruction he has witnessed. Instead, he is invigorated by the direct emotional response people have to his images. “There’s nothing more gratifying for me than hearing from viewers who say, ‘What can I do to help?’ Photography is a powerful tool that can really have an impact,” he says. The possibility of making a difference serves as Beltrá’s motivation.

Beltrá isn’t depressed by the destruction he has witnessed. Instead, he is invigorated by the direct emotional response people have to his images. “There’s nothing more gratifying for me than hearing from viewers who say, ‘What can I do to help?’ Photography is a powerful tool that can really have an impact,” he says. The possibility of making a difference serves as Beltrá’s motivation.

Through his oil spill work, and years of campaigns funded by Greenpeace, Beltrá has a constant international platform on which to raise awareness about conservation. In fact, his photographs have been used in nearly every Greenpeace campaign for the last 20 years. Beltrá has made a career from photographing the world’s most precious ecosystems, and the passion for what he loves is captured and conveyed instantly in his evocatively poignant imagery.

A Fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers (ILCP), Beltrá traveled to Northern British Columbia the end of last year to capture the landscapes, wildlife and people of a region threatened by a planned transcontinental oil pipeline. The pipeline will bring millions of barrels of oil from the tar sands of Alberta through the Great Bear Rainforest.

The photographer’s commitment and dedication to conservation have not gone unnoticed. In April 2009, Beltrá was awarded the prestigious Prince’s Rainforest Project. The award, granted by Prince Charles in a private audience, sent the photographer to the Congo, Amazon and Indonesian rainforests for three months to create photos for a book, website and several exhibitions on the imperiled status of the world’s rainforests.

In 2011, Beltrá was also awarded the Special Prize by the Jury from the Days Japan International Photojournalism Awards, along with an Award of Excellence for Pictures of the Year International and a Gold Award of the China International Press Photo contest for his work on the Deepwater Horizon Spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Within the past two decades, Beltrá’s passion for conservation has taken him to all seven continents and includes several expeditions to the Brazilian Amazon, the Arctic, the Southern Oceans and the Patagonian ice fields. His work has been published by such prominent international publications as The New Yorker, Time, National Geographic, The New York Times, Le Monde, El Pais and many others.

Beltrá continues to photograph some of the last remaining pristine places on the planet.

For more information, go to www.danielbeltra.com.

Daniel Beltrá’s BP Oil Spill Slideshow