Canada and its First Nations Moving Toward Reconciliation & Forgiveness

On 11 June 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper delivered in Parliament a Statement of Apology on behalf of the Government of Canada to survivors of Indian Residential Schools. In the apology, the Prime Minister stated that the entire ‘policy of assimilation’ implemented by the system of Indian Residential Schools ‘was wrong, has caused great harm and has no place in our country.’ The Prime Minister further committed to ‘moving towards healing, reconciliation and resolution of the sad legacy of Indian Residential Schools . . .’ and the ‘implementation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement,’ according to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

. . . For far too many youth, suicide is the ultimate way out. We’re seeing that more and more in remote, northern communities. This is truly the saddest commentary. I can’t imagine how bad life must be for a twelve year-old Cree boy to hang himself at the recreation centre swing-set. To not have the love he needs . . . to not have hope. To know that he hasn’t been the first and he won’t be the last. — Anishinawbe Blog by Bob Goulais

With First Nation youth suicide rates conservatively five to seven times higher than those of non-Aboriginal youth and 11 times higher for Inuit youth, many people speculate on the causes of this ongoing catastrophe affecting North American youth. Experts maintain that the obvious causes are isolation; poverty; lack of decent housing, education, healthcare and social services; and unemployment. However, ask an Aboriginal or tribal person and residential schools will be at the top of his/her list. Congressionally approved, legally enforced, government-funded and run by Christian churches in both Canada and the United States from the mid-19th Century to the mid-20th Century, such schools were, arguably, a product of white “Christian” colonization. The specific focus seems to have been less on education and more on assimilating Canadian First Nations and U.S. tribal people with Euro-Canadian and Euro-American, respectively, populations, language, heritage and customs.

The blog Sweetgrass Coaching, written by Richard Bull, explains this theory by stating:

When Canadian society says we’re sick that’s like a psychopathic killer complaining to someone he’s tried to strangle repeatedly that she should do something about the marks on her neck and see a psychiatrist about her recurrent nightmares and low self-esteem.

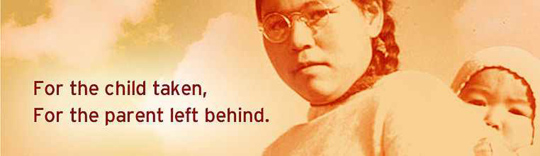

Removed under duress, wherever necessary, from their parents in both the U.S. and Canada, the children endured intellectual, cultural, spiritual and familial desecration as a result of this coerced “education.” According to Canada’s TRC, more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children from the 19th Century until the 1970s were forced to attend these Christian schools against their parents’ wishes. Later years brought to light the horrific physical, emotional and sexual abuse that many children endured during their years in these residential schools – far away and mostly inaccessible from the love, help and support of their families and tribes. More than 130 of these schools were scattered across Canada, with the last one closing in 1996.

Photo Credit: Truth and Reconciliation Committee

The TRC explains, “While there is an estimated 80,000 former students living today, the ongoing impact of residential schools has been felt throughout generations and has contributed to social problems that continue to exist.” Many regard the unresolved trauma, pain, resentment and anger as the true generational legacy of this discriminatory Canadian practice. The Anglican Church of Canada operated 35 of these schools within Canada. It concurred with the experts’ and former students’ historical analysis when it commented in its Anglican Journal: “For many of Canada’s Aboriginal children, the residential school experience taught them to hate themselves, their families and their culture.”

The Honouring Life Network

To help combat suicide among First Nation youth, the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) launched the Honouring Life Network (HLN) in April 2008 with funding from Health Canada. The network contains a variety of resources, such as a blog, website and social media that support and connect the youth in a positive way. Nicole Robinson, HLN’s program coordinator, explains: “There are many communities, groups and organizations running successful and inspiring youth-oriented programs in efforts to reduce these First Nation suicide rates. Yet, we rarely hear about these success stories, instead focusing on the tragedy and devastation.”

To help emphasize these positive stories, HLN sought funding to produce a series of documentaries about successful Aboriginal youth programs in different communities across Canada. The documentaries acknowledge and celebrate different approaches to suicide prevention strategies while concurrently building awareness and potential partnerships among organizations that support the health and well being of Aboriginal peoples. According to Robinson, these success stories demonstrate that implementing positive youth programming is not impossible. And, in so doing, the videos offer First Nations, Inuit and Métis individuals and communities hope for their own community and a future for their youth.

Bimaadiziwin: “Living in a Good Way.” This documentary was filmed at southwestern Ontario’s Walpole Island First Nation and is about the success of their Bkejwanong Youth Facility (BYF). Robinson explains, “The community recently set a new long-term goal or direction, ‘bimaadiziwin,’ which means ‘living in a good way’ in Ojibway. As part of this direction, community leaders recognized that to create community change you have to start with your youth.

“The idea of ‘bimaadiziwin’ has been applied throughout the Walpole Island First Nation using the concept of ‘the three Cs:’

- Everybody COUNTS – the recognition that every human being is uniquely gifted by the Creator and, therefore, cannot be excluded. This means every community member has value in the wellness of that community.

- Everybody CONTRIBUTES – communities often search for resources to improve its community life. However, a community’s people – in particular its youth – are its greatest resource. Just by being there, each member of a community is contributing, and communities need to figure out how to tap into that resource. Healthy communities are those which value and cultivate the resources that exist within their population.

- Everybody can CELEBRATE – celebration needs to happen as a whole community. Many Aboriginal communities have become segmented, which is why a need exists to bring back value to communities as whole beings. Walpole Island First Nation is planning a community feast where they will announce the names of all the people who were born or passed away in the past year as a way of celebrating the individual people and their contribution to the community.”

Songedamowin: Trust. This documentary was filmed at Ottawa’s urban health centre, the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health. The Algonquin title, Songedamowin, means “trust” or “to trust,” which is the centre’s more important goal as it works to acquire the trust of its clients by creating a space and place that creates a sense of wellbeing and cultural identity.

© iStockphoto.com/bloodstone

The youth who is interviewed in the documentary sees the people at Wabano as trusted friends who emphasize the importance of goals and aspirations. The Wabano staff not only helps the youth get back in-touch with his identity, they also teach him how to trust others, as well as himself, so he can take on responsibilities and make a positive contribution. Maintaining trust is just as important as building it, and Wabano is run so people, especially youth, always have someone they can call.

Robinson explains: “The strength of Aboriginal people lies in their culture. It is within every Aboriginal individual, but they have to work to bring it out; they have to find their voice. A person cannot be well until he/she knows who they are. This is what Wabano does so well: It is a place that holds Aboriginal identity and values, and allows clients to find this in themselves.”

Support. This documentary was filmed on Baffin Island, Nunavut in the small Inuit community of Clyde River. The film explores the impact that a hip hop program at the Ilisaqsivik Centre has had on local youth. The basic format consists of a weeklong workshop, which uses hip hop to engage youth and then delivers positive wellness messages once they are worn out from dancing and performing. Hip hop becomes the vehicle for empowerment – an opportunity for youth to express who they are and the art they bring to the table.

According to Ilisaqsivik Executive Director Jakob Gearhead, “Hip hop is the smallest part and the biggest part; it’s the hook; it’s what will bring the kids there.” As a result of the program, the community saw an immediate reduction in suicide ideation, solvent abuse and smoking. Since the program’s inception in 2006, many youth have returned to school, 10 have stopped smoking and six have stopped using drugs.

Robinson says that “participating youth value the program not just as ‘something to do,’ but also as a way to feel welcome and valued, and to participate as a member of a team. As one youth said, ‘Hip hop gave me the opportunity to shine and to get noticed instead of just laying low and doing drugs.’”

Lessons Learned from HLN Documentaries

Youth are a community’s future and, therefore, its most precious resource. They need to be treated accordingly; they need to feel they are valued members of the larger community. Today’s youth live in a very different world from their parents and grandparents. They have different expectations and demands, and youth activities and programs should be designed accordingly and run in collaboration with community youth.

According to Robinson: “Building and maintaining trust between staff and youth is critical when working with Aboriginal youth. An essential component of trust is ensuring youth always have a connection to the centre or program – that they feel confident they always have someone to call, or that someone will be available to open the hall for dance practice. Unfortunately, many youth-targeted programs fail because the youth are let down by supporting adults. Youth need to feel like they are important to community adults and elders. This makes them feel like they matter and can talk to these adults/elders. If the adults lose interest in the program, the youth will too.

“The final lesson for Aboriginal people is that strength lies in culture. People will be unwell until they know who they are. Helping Aboriginal people learn about where they came from is an essential part of helping them to be well.”

© iStockphoto.com/Spiritartist