Nature & Adaptability: Solutions for an Uncertain World

Much needed and welcome growth is occurring in the business of looking to nature for ideas and inspiration on how people can make society function better. Initially, these adoptions seemed to come in the form of “ah ha” moments, as when a burr stuck to an inventor’s clothes gave him the inspiration to create Velcro. More recently, “green design” has tried to more systematically incorporate nature’s ways of doing things into buildings, furniture and spaces. But the real power in learning from nature is not in copying its products to improve how people make products but in incorporating its processes to improve how people process the complex and ever changing world around them.

The most important process in nature for living in a complex world is adaptability. Adaptability is what has allowed all organisms, from the beginning of biological time some 3.5 billion years ago, not only to survive but also to thrive. And although humans have been on Earth for just a fraction of time, and used a fraction of that fraction of time to transform it and to live in communities and cities scarcely resembling other living things, they still share the same basic problem as all living things.

The problem is that the world is full of risk and almost completely unpredictable. Adaptability is the common solution to this common problem because it confers the amazing power of being able to live with risk and to deal with uncertainty. Just like fish living in shark-filled waters, birds migrating across hemispheres and immune cells fighting off viruses, human emergency responders, military officers, school teachers, CEOs and middle managers all need to be adaptable to deal with the fact that the world is always changing and never completely safe.

Certainly, all these groups of humans and their organizations are starting to talk about adaptability. But does adaptability really work, or is it just another corporate buzzword that will be peppered over PowerPoints for a few years and then replaced by a newer fad? Consider this: Adaptable biological organisms have thrived in a world of extreme and unpredictable risks for 3.5 billion years. Not even IBM has that kind of longevity. These organisms have also diversified into more than 10 million different species and covered the planet from the deepest to the highest to the wettest to the driest environments. Not even Google has that global reach. And because they have been fossilized, studied intently and still roam, grow and evolve on the Earth today, these organisms have collectively created a database of case studies on how to manage chaos and uncertainty, which is unmatched in any human archive, including the internet.

Three remarkable things exist about nature’s immense database. First, every single data point in this almost infinite natural database points to a way to be adaptable. Second, this knowledge base is completely open access. No one owns the IP, and no password is required to access it. Third, and most surprising, only a few creative companies, innovative managers and forward thinking organizations have made any attempt to query this database and to use its knowledge. When they have, they have been remarkably successful.

© iStockphoto.com/Antagain

So, why isn’t the world’s best, free database on how to be adaptable being used by companies, government agencies and managers that desperately want to be more adaptable? The answer is because it is written in a code most people have forgotten how to read. A person cannot learn to read biology in a board room. And, when one spends too much time behind the confines of a computer screen, the natural world seems ever more distant – too complex and unfathomable to be understood, let alone be of immediate use.

But, an increasing movement to understand how humanity’s separation from nature is hurting it is occurring on a number of levels. This includes physical and psychological maladies to misunderstanding the science behind evolution and climate change to a failure to understand how complex systems work and affect all aspects of society. These realizations are pointing human beings back to old ways of discovering the world – when the pastime of natural history was an extremely popular way for men and women of all walks of life to understand nature and its changes. And, they remind people of the wisdom of earlier biologists like Charles Darwin and Edward Ricketts (appearing in several books authored by his good friend John Steinbeck), who saw no fundamental difference between the lives of animals and those of humans.

In this spirit, it is possible to carefully examine nature’s database with an eye on how the function of adaptability works and how it can be applied to a broad range of societal challenges. What is reassuring is that this enormous database reveals just four simple practices common to most adaptable organisms. And, these practices are bound by a simple set of guidelines: Adaptable biological organisms do not plan, do not predict and do not try to perfect themselves.

No one would ever plan a fish to look like the ocean sunfish Mola mola. Yet, this homely creature has mastered the art of survival for millions of years. Beyond the imperfect copies of its ancestors’ DNA it is born with, each organism on Earth hits the ground or the sea with no long-term plan except to survive and to reproduce, and that is a good thing. It will need to meet a wide range of unexpected challenges, and it needs to be flexible enough to solve them. At the same time, it does not want to burden its own offspring with inflexible plans that make them unable to meet their challenges.

Too often, people and organizations confuse planning with being prepared. But the most successful entities, just like the most successful organisms, get there by relentlessly solving challenges that arise and by exploiting new opportunities that become available. Nature never had a plan to turn single-celled bacteria into porpoises, platypuses and people, but that is what happened. Likewise, in 2003, if Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg had said, “I have a 10-year plan to turn my computer program, which rates the attractiveness of my college dorm mates, into a worldwide network of nearly one billion people that fundamentally changes the way humans communicate,” would anyone have invested in it?

© iStockphoto.com/baojia1998 | Before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami reached Sri Lanka, many animals, including elephants, moved to high ground and survived.

Did the animals that acted so strangely before the enormous Boxing Day tsunami in Asia predict it, or were they just really good at observing the early warning signs? The answer lies in the rarity of a huge tsunami. Evolution has ruthlessly weeded out from organisms any desire to expend resources predicting the future state of an inherently unpredictable system, especially for such rare and unpredictable events as a tsunami. In its place, adaptable organisms have astonishing observational skills. The signals of vibration, noise, smell and magnetism those animals experienced on the morning of the tsunami were so unlike their usual observations that they became very nervous. And, domestic animals even tried to tell their relatively clueless human compatriots about their fears.

Too often people try to substitute predictive models for intensive observation of the world. But in the business world, where multi-billion dollar consultancies have thrived from selling all sorts of predictions, the failures far outweigh the successes. Try to recall a device released in 2001 to astonishing predictions that it would be “bigger than the PC.” Now try to recall anyone besides a mall cop using the device – a Segway Personal Transporter.

If the great white shark is such a perfect predator – as the Discovery Channel constantly claims – why doesn’t it have laser beam eyes? The idea that evolution trends towards perfection, or is about “survival of the fittest,” is absurd. Not only would it be impossible to determine what is perfect in nature, organisms in nature have no need to be perfect. They just need to be good enough to survive and to reproduce their genes for another round. That is why Darwin said, “It’s not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”

Likewise, the success or failure of organizations has little to do with how close to some assumed perfection they are but how well they adapt to change. For decades Kodak dominated the consumer camera market, but they were unresponsive to the shift towards digital cameras because early efforts at digital were so unimpressively far from optimum. As a result, six less equipped but more adaptable players – some with zero previous photography experience – left Kodak in their wake.

The Four Practices of Adaptable Systems

The guidelines above may seem a bit unsettling to organizations and managers used to falling back on planning processes and trying to motivate employees with calls to “give 110 percent!” Fortunately, positive guidance from nature is found by looking at how exactly organisms in nature solve problems without being able to plan, predict or perfect themselves. By using practices of adaptable systems – as most forward-thinking businesses, government agencies and individuals are doing already – the nervous uncertainty of considering unplanned, non-optimal problem solving can be quickly alleviated and replaced with a creative excitement that can propagate across social networks and throughout an organization.

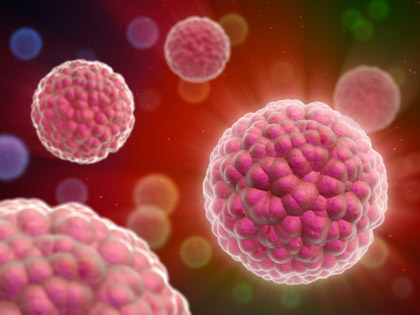

The first practice is decentralization. The most successful biological organisms have an organization that eschews centralized control in favor of allowing multiple agents to independently sense and to quickly respond to environmental change. The human immune system trusts millions of cells all over the body to look for, and neutralize, invading pathogens without any conference calls to the brain to plan and to execute an appropriate response.

Leaders and managers need not fear this kind of organization. The independent sensors of adaptable organisms are not anarchists. They are still part of a recognizable body, and they rely on the resources and overall direction the body gives to them.

© iStockphoto.com/Henrik5000

Many recent examples have shown this kind of decentralized organization to be highly effective in head-to-head competition with traditional centralized ways of solving problems. Think Space X vs. NASA, DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) Grand Challenges vs. Department of Defense single-source contracts, Wikipedia vs. Encyclopedia Britannica or Google Flu Trends – which use the power of billions of users independently searching for flu-related terms on Google to map out accurate trends in flu outbreaks – vs. the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention flu reports that can provide the same results but two weeks later.

The second practice is to cultivate redundancy. The biologist J.B.S. Haldane was purportedly once asked “What do all your studies tell you about the nature of the Creator?” to which he replied, “He must have an inordinate fondness for beetles.” Beetles have dominated the Earth, and they have diversified into thousands of different forms by creatively transforming a key element of natural adaptability – redundancy.

People tend to shudder at the word “redundancy” because they think it means the same as “wasteful” or “inefficient.” But if redundancy is so useless, why is it so common in nature? Human DNA is filled with redundant sequences; most organisms produce more offspring than needed to effectively reproduce themselves; and ecosystems are filled with a diversity of species – each a redundant part making the ecosystem as a whole resilient to disturbance, unpredictability and change. A fairly simple redundancy exists in nature, such as the multiple copies of walking legs in centipedes. Another redundancy is what paleontologist Geerat Vermeij calls “creative redundancy,” which is the transformation of simple redundant parts into specialized interacting units. Beetles are the evolutionary product of creatively turning multiple walking legs into wings, claws, camouflage, armor and devices for shooting chemical weapons.

When a kidney fails or a loved one desperately needs a healthy one, people begin to respect nature’s redundancies, but they still continually try to eliminate redundancy in their own lives. This comes from too narrowly viewing wasteful aspects of redundancy. Smart businessmen and managers know how to use redundancy effectively at every level of their operations. Southwest Airlines’ fleet includes 698 of the same type of plane, which means every pilot knows how to fly every plane in their fleet; every maintenance worker knows how to fix every plane; and every spare part fits every plane. That is simple redundancy at work.

Equally successful is the creative redundancy shown by Geico Insurance, which defied all marketing conventions by running simultaneously up to six completely different campaigns, including the Cockney-accented gecko, metrosexual cavemen and creepy stack of money. All are different ways of getting the same simple message across: Geico insurance is an easy way to save money. This multiply redundant campaign is largely credited for Geico’s quintupled market share throughout the last 16 years and its transformation from near bankruptcy to the third largest insurance carrier.

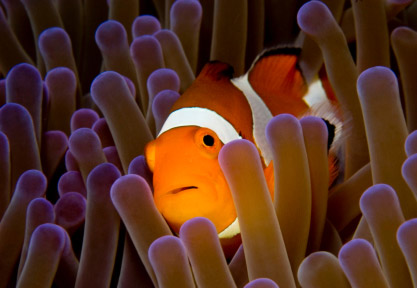

The third practice is to develop symbiotic partnerships. In nature, no organism does it alone. Every organism is actually a collection of relationships with other organisms known as symbioses. These relationships extend any organism’s own adaptive capacity far beyond its innate abilities. Symbiotic relationships take a huge multitude of forms from mutually beneficial partnerships to coercive co-dependencies in which one partner gets far more benefit than the other.

© iStockphoto.com/strmko

Symbiotic relationships also occur between the most unlikely of pairs, such as small scavenging fish and large predators. As long as both parties get some benefit, these relationships will persist, some for so long that the organisms become inseparable. Remarkably, a huge number of natural symbioses most likely developed out of previously hostile relationships.

By focusing intently on problem solving, remarkable symbiotic partnerships can emerge even between mutually hostile groups of humans, such as Israelis, Palestinians and Jordanians, who are now working together to combat infectious disease. Remarkable symbioses also exist among the best managed businesses. Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream, known for its strong brand following and equally strong commitment to supporting local agriculture and to donating profits to social justice and environmental causes, would seem a terrible match to Unilever, a multi-national food and beauty products conglomerate with fairly anodyne brands. But they each had problems to solve.

Ben and Jerry’s recognized their need to grow so they could do more social good through profit sharing. Yet, they were sitting on years of flat and declining sales. Unilever simply needed to catch up in the niche markets of “boutique” food brands and super premium ice cream. When Unilever ultimately made Ben and Jerry’s an offer it couldn’t refuse, both sides recognized the need to maintain the socially responsible image of the company. As a result, Unilever adapted in everything from casual dress for its Ben and Jerry’s executives to maintaining the brand’s charitable giving. The result is a Ben and Jerry’s brand that can give far more to charity with the larger distribution and marketing of Unilever. And a more diversified Unilever has also expanded its commitments to sustainability by incorporating aspects of Ben and Jerry’s DNA throughout its corporate practice.

The fourth practice is to learn from success in order to generate a feedback engine that self-generates adaptable practices. All organisms in nature learn, within their lifetimes and across generations, to become better at what they do. Some of this learning comes from failure, but this is literally a dead-end kind of learning. If a person fails to pass on genomes because of the way he/she lived, the learning stops. The process of learning from success is far more vital in natural systems. It is a recursive process that can efficiently build new innovations on a platform of past successes. By reproducing the natural variations – color, predatory behavior or mate choice to name a few – that are successful, biological organisms diversify and thrive, not just in their own lifetime but in subsequent generations as well. Every successful offspring, meaning every living thing seen or not seen on Earth, is the product of the imperfect successes of its parents.

Management literature is, unfortunately, rife with advice to “learn from failures.” One article from the 1990s in Harvard Business Review even held up BP as an exemplar of a company that learns from failure. Certainly BP has learned much from the failures of the recent Deepwater Horizon disaster, but that is little help neither for the 11 workers who lost their lives nor for the devastated Gulf environment and economy. Learning from failure may make business more prepared for the disaster that has already happened, but it does nothing to prevent the disaster in the first place. Rather than BP’s culture of learning from failure, it is learning from success that could have been of great help in the Gulf oil disaster.

Only a few years earlier the Coast Guard had successfully cleaned-up a nine million-gallon oil spill in the Gulf after Hurricane Katrina under the worst conditions imaginable. Unfortunately, few knew those lessons because the federal government’s massive “after action” report, which featured more than 100 recommendations about dealing with all the failures of the Katrina response, did not mention the success of the oil spill cleanup at all.

Kickstarting Adaptability

All of the practices above are inherent in nature itself. Natural ecosystems are diverse, resilient and even beautiful because they are made up of organisms, cells and genes that are each in their own ways using decentralized, redundant and symbiotic approaches to solve challenges in their environment.

© iStockphoto.com/agsandrew

And, they learn from their successes through replication and reproduction. Instead of running roughshod over ecosystems – as humans did when they carved a shipping lane through Louisiana’s wetlands (a pathway known as the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet that became a red carpet for Hurricane Katrina) – people should not only protect them but also adopt their practices in daily lives.

A simple step exists for anyone who wants to safely inculcate adaptable practices: It is to switch from giving orders to issuing challenges. An order is when a leader or small group of supposed experts decides what is best for everyone in their world and tells them what to do. By contrast, a challenge is when a leader identifies a critical problem and asks anyone to contribute to the solution. The incentive for responding may be a $1 million check or a certificate of achievement. It usually does not matter as long as respondents believe the challenge is interesting, and they are committed to the mission of the organization issuing the challenge.

Challenge-based problem solving ends up naturally incorporating all practices of adaptable systems. By issuing the challenge broadly, multiple independent agents work to solve the problem. When these independent agents respond, it brings a creative redundancy that often results in unexpected solutions. In one of the first recorded challenges in which the early 18th Century British Parliament offered a prize for solving the problem of identifying a Sailor’s longitude at sea, it turned out to be a watchmaker who solved the challenge rather than an astronomer (as was expected to win). When these multiple redundant agents come together, they invariably realize they need each other’s skills to solve the challenge, and natural symbiotic partnerships emerge based on the problem at-hand. Finally, one can continue to realize benefits from challenge-based problem solving by culling from the winning solutions ideas for issuing a next generation challenge.

Almost everywhere challenges have substituted for orders, such as in the Department of Defense, space exploration, Fortune 500 companies, medicine and mathematics, and environmental restoration. Leaders have been amazed to find they have solved problems more effectively, quickly and inexpensively than they could have imagined. Just as today’s explorers of the natural world continue to be amazed by new findings, those who incorporate nature’s practices will find a continual source of wonder and satisfaction at the power of adaptability.