Saving Serengeti

It is one of the most famous names in the world. Almost any schoolchild, no matter where, can tell you about it. Many companies and services have adopted the appellation. Sunglasses and clothing lines are named for it. A Google search turns up 16M references. The very name rings with the sound of the exotic. It has become an icon of wild places.

Serengeti

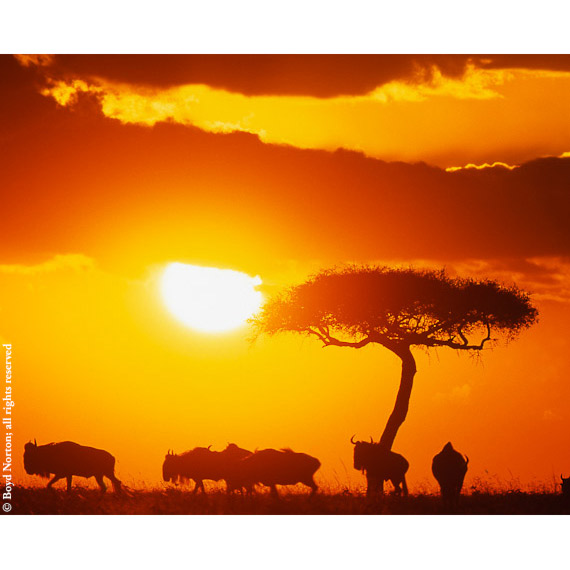

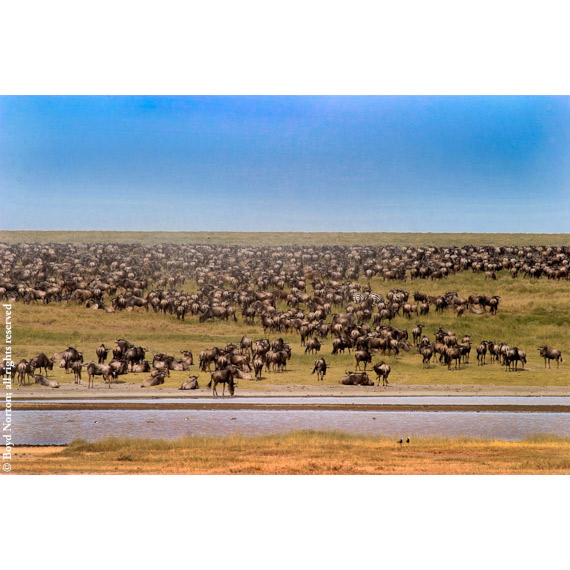

The Maasai call it “siringet” in that expressive and lyrical language of Maa. It means “extended” or “endless,” a place that goes on forever. They do appear endless – the plains that comprise a large part of Serengeti. The Serengeti National Park encompasses 5,700 square miles, an area larger than Connecticut. However, the ecosystem does not end at the national park boundaries. The total Serengeti ecosystem, which includes Kenya’s Masai Mara Reserve, Ngorongoro Crater Conservation Area and adjacent reserves, such as Loliondo, Maswa, Ikorongo and Grumeti, is almost 10,000 square miles – almost three times the size of Yellowstone National Park. While this may seem an excessively large area to preserve, it is important to realize that it needs to be large in order for the life-cycles to continue as they have for thousands of years. Serengeti is one of the very few reserves left on earth that protects and contains such a complete ecosystem and the succession of life that takes place within it.

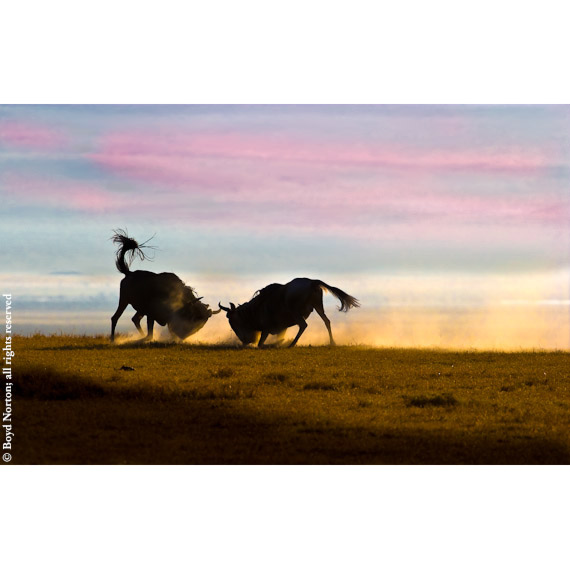

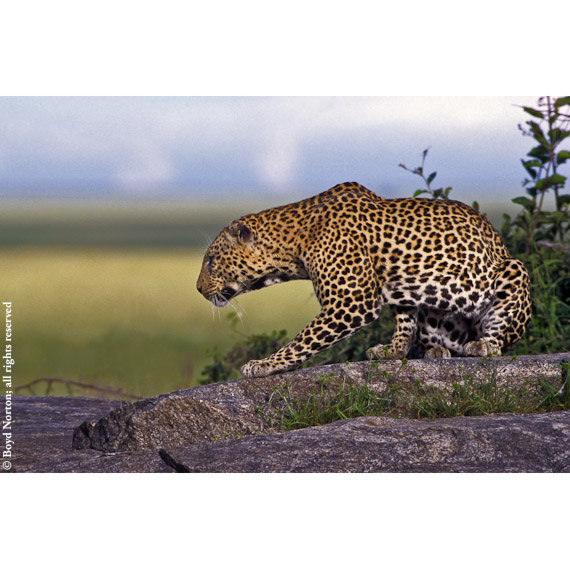

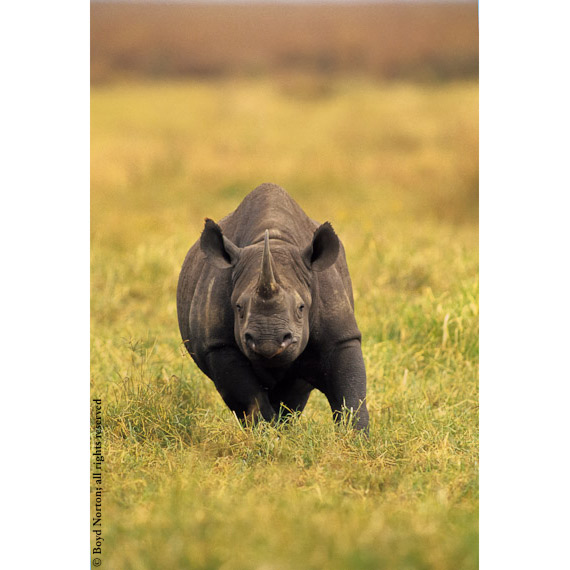

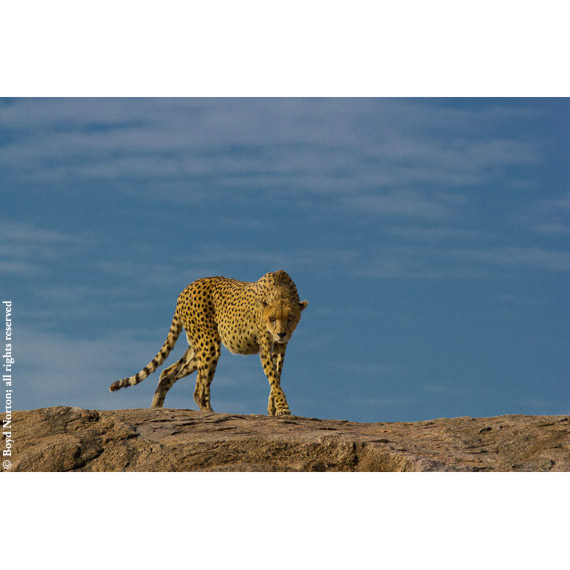

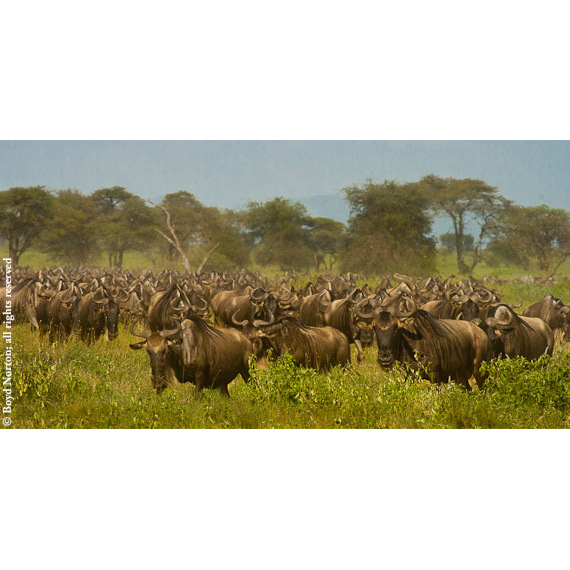

Perhaps the most famous feature of Serengeti is the Great Migration. It has been called “the greatest land mammal migration on earth” and for good reason. Each year upwards of two million animals – wildebeest, zebras and certain other herbivores – make a long journey from the eastern plains through central Serengeti and northward to Masai Mara and then return in a yearly cycle in search of water and fresh grasses. It is an incredible spectacle; grazers, predators and all other animal life are woven into the fabric of this intricate ecosystem. To experience all this interactivity of life is like seeing the world when it was young.

For nearly 30 years I have been traveling to the Serengeti ecosystem annually, leading photo tours and working on book and magazine assignments. I had always assumed the protected status of these lands – national park and game reserve designation, World Heritage Sites (Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti National Park are so designated) – would protect the region in perpetuity. But I was wrong.

Boyd Norton

In May 2010, I was in the Loliondo Game Controlled Area just east of Serengeti National Park when I learned from Maasai friends of plans by the Tanzanian government to build a major commercial highway. This highway would slice, like a knife wound, across the northern part of the park and across Loliondo itself (where parts of the migration pass through). It was projected that hundreds, if not thousands, of big commercial trucks would speed each day from towns on the shore of Lake Victoria lying to the west through the Serengeti ecosystem to Arusha on the east. The impact on the migration would be enormous. Even worse, this development would open the region to settlements on the fringes of the park, and the highway could become an avenue of poaching. This proposed highway was the single greatest threat to Serengeti National Park in its entire history.

When I returned home I posted this discovery on my Facebook page. I was greatly disturbed by this threat, and I hoped others would be as well. Within days people began contacting me. In a week a few of us had started a new Facebook page, Stop the Serengeti Highway. Word soon spread, and in a couple of months thousands of followers were on the page. (Today, the Facebook page has more than 45,000 followers; most interact in useful and meaningful ways, providing information and contacts.)

We needed an action plan. An old friend and colleague, and early ecotourism pioneer in East Africa, Dave Blanton, compiled a database of more than 300 scientific researchers who had knowledge of, or worked in, the Serengeti region. When he polled them, an overwhelming number thought this commercial highway could spell the end of the great migration and, along with it, a massive die-off of wildlife up and down the food chain.

We then blanketed select news media around the globe with this information. Surprisingly, there had been very little news of this devastating proposal outside of East Africa. News stories began to appear across various media outlets in Europe and North America. No longer was this a local issue. The fate of the Serengeti ecosystem, iconic for its wildlife, was becoming a global concern.

Boyd Norton

The Tanzanian government reacted defensively, emphasizing the need for improved infrastructure to serve communities along the eastern shore of Lake Victoria. Without doubt, vastly improved infrastructure is needed in the region. Tanzania is a poor country, and though its economy has improved greatly in recent years, transportation of goods and services is poor in most places. However, tourism has become a $1.8 billion annual income earner and employs an estimated 600,000 people. Most of the tourists come to the Serengeti ecosystem. The collapse of this ecosystem could greatly diminish the tourism income.

Moreover, being a poor country, could Tanzania pay for this expensive highway development? It was a recurring question. No one seemed to have an answer. But the Tanzanian government insisted it would be built. But, by whom?

In December 2010, a possible answer emerged. One of our media contacts, Richard Engel, chief foreign correspondent for NBC News, traveled to Serengeti and in his investigation came up with an answer: China. Presenting on NBC Nightly News, MSNBC and the Today Show, Engel asserted that China was after the mineral coltan (an important ingredient in cell phones) and certain rare earth minerals (used in a number of electronic devices). It seemed logical. There had been other reports in a number of African countries of China peddling influence, offering aid in return for resources.

In the past year the situation has become even more complex. Oil discovery in Uganda has entered the picture. The Ugandan and Tanzanian governments signed a letter of understanding with a Chinese construction firm to investigate the development of a transportation corridor from Lake Victoria to the Indian Ocean coast, presumably across Serengeti. This corridor would include a railroad as well as highway. The combination would certainly be the death knell of the migration and of the Serengeti ecosystem as well.

Still another element in the controversy: South Sudan. With rich oil deposits already developed and producing, this newly independent country is reliant on an oil pipeline crossing Sudan to a Red Sea port. The government of Sudan is threatening to shut down the pipeline. China is the recipient of 70 percent of that oil. Thus, landlocked South Sudan may well be forced to join with landlocked Uganda, its neighbor to the south, to get its oil to the Indian Ocean coast through Kenya or Tanzania or both. And, China will probably pay for this transport; it needs the oil.

Boyd Norton

Early in this battle we proposed an alternate to the Serengeti highway route, one that would bypass the Serengeti ecosystem entirely. (See map.) Moreover, this southern route would serve four times as many towns and villages. Though slightly longer than the proposed Serengeti highway, parts of this southern road already exist and are being upgraded for major transport right now. Both the World Bank and the German government offered funding to aid this project. The Tanzanian government was strangely silent about the offer. (Early in the battle, a spokesperson for the World Bank informed us they would not fund the proposed Serengeti highway and cited the potential impact on the ecosystem.)

While many of the concerns over the fate of Serengeti have been global, local and regional environmentalists have joined with us to protect and to preserve the ecosystem. In December 2010, a Nairobi-based organization, African Network for Animal Welfare (ANAW), filed a lawsuit in the East African Court of Justice to halt the Serengeti highway and cited the detrimental trans-boundary impact on the Masai Mara Reserve (a major tourist destination in Kenya). Last year, the government of Tanzania attempted to have the case thrown out. But, on March 15, 2012, the East Africa Court of Justice Appellate Division dismissed all objections raised by the Tanzanian Attorney General and ruled that the regional Court did indeed have jurisdiction to determine such environmental disputes in the region. The case will now go to full trial, and a win here could possibly mean long-term protection for the Serengeti ecosystem.

Serengeti Watch, a tax-deductible non-profit started in 2010 by Dave Blanton and me, has raised sufficient funds to give a substantial grant to ANAW to help with legal costs. In addition, another large grant was given to a local environmental group in Tanzania to begin organizing grassroots support for protecting Serengeti. Long term, the overall aim of Serengeti Watch is to fund projects in media, journalism and education that build capacity for young Tanzanians to become opinion makers and culture builders. Through photography, writing, video, music and other artistic expression, we plan to give local people the ability to communicate issues of conservation and its importance.

This may be the best way to protect Serengeti for the future.

For all of us, Serengeti is the land of our youth. It deserves our utmost care, even if we live thousands of miles from it, even if we never visit it. It is vital that it remain, in the words of famed psychologist Carl Jung, the “stillness of the eternal beginning.”

Boyd Norton’s Serengeti Slideshow