Tropical Coral Reefs & Changing Oceans

As soon as the divers venture from the shadow of the ship floating above, a cloud of tropical fishes surround them. Bright purple, black, green and yellow, they dart around like bees in a hive. Large blue parrotfishes wander through and lazily bite off bits of corals with their parrot-like beaks. Wary of the looming shape of the divers, small nemo fish burrow between the poisonous tentacles of their protective anemones while the large head of a moray eel peaks out from the entrance to its lair, its mouth open in threat. Down in the sand, a few sea cucumbers avoid a sea urchin’s black spikes as they make their way slowly along the seafloor. And, a blue-spotted ray, half-buried in the sand, lies waiting nearby while colorful sponges peak out like chimneys from amongst the coral. Elaborate, three-dimensional structures, the coral species outgrow each other as they compete for space in the sunlight. The divers, awed by such display of color and motion, could be forgiven for believing tropical oceans to be ebullient with life. The truth is actually the opposite.

Sadly, the extraordinarily high levels of productivity in coral reefs are not the norm in tropical oceans. Undersea visibility gives it away because one can only see through water when it is empty, when not much is living in it. Colder and nutrient-rich waters at higher latitudes support life in huge numbers – where divers cannot usually see far. In contrast, warm and clear waters off beaches of white sand and scattered palm trees, so often featured on holiday postcards, are mostly dead. True oases in an empty water desert, coral reefs flourish where they do through clever natural engineering. Thanks to microscopic algae living within their tissues, corals receive most of their energy directly from the sun itself. Nutrients are a scarce commodity in tropical waters. And, the coral ecosystem excels at recycling and reusing its limited resources with hundreds of animal and plant species playing different roles in a delicate balancing act. It all works extremely well. With a biodiversity rivaling tropical rainforests, their land counterpart, coral reefs are home to nearly one-third of all marine living creatures. Their future, and that of their inhabitants, is currently in jeopardy.

Threats to Coral Reefs

Approximately 20 percent of the world’s coral reef ecosystems have already been lost. Confined to clear and shallow waters, coral reefs are vulnerable to a range of pressures, both human and natural. Overfishing, pollution, increased sedimentation and disease have already taken their toll. In the 1980s a combination of overfishing and pollution had so weakened Caribbean reef ecosystems that when a natural disease struck sea urchins – one of the few herbivores remaining after fish populations had declined – algae took over many reefs. Corals compete with algae for control of the seafloor, and herbivore grazing is essential for keeping algae at bay. Scientists believe that once control has been relinquished and the ecosystem has shifted to dominance by algae, it will not be easy for corals to claim it back. In many tropical countries, and despite laws trying to prevent it, fishermen still throw dynamite into the waters, killing fish and, at the same time, destroying their ecosystem. This, then, becomes home to the next generation – a place where no one will have a chance to catch fish.

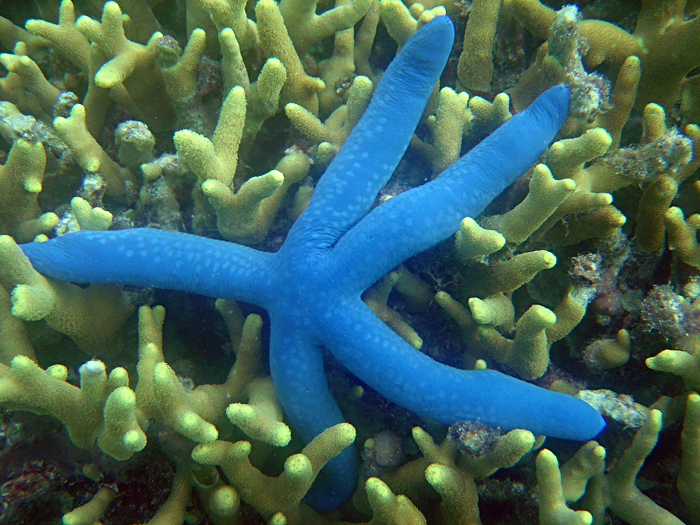

Other fishermen dive down to release poisonous cyanide amongst corals, killing them, the fish nearby and everything else that comes in contact with it. And, ship anchors dropped carelessly routinely destroy centuries-old coral colonies. Perhaps more insidiously, conversion of many wild areas to farmland is resulting in increased sedimentation and pollution, which is brought by rivers into oceans and affects coastal ecosystems. In the Great Barrier Reef off Australia’s coast, outbreaks of a predatory starfish – the Crown of Thorns – have been causing mass mortality of corals since the 1960s. Already weakened by human pressures, coral colonies are often unable to recover. The significant global decline in recent decades has placed one in three known coral species at critical risk of extinction. Now, the global threat of climate change is growing to dominate above all others.

Canaries in the Climate Change Coalmine

Not so long ago, coal miners used to take caged canaries down into mines as an early warning system of the presence of toxic gases. As long as the bird kept singing, miners knew the air was safe to breathe while a dead canary prompted an immediate evacuation. Today it is coral reefs that are playing a similar role in the coalmine of anthropogenic climate change. Burning of fossil fuels is releasing CO2 to the atmosphere at a rate likely unprecedented in the history of the planet and creating a period of rapidly shifting conditions in oceans. Part of the CO2 remains in the atmosphere and captures some of the heat radiated by Earth in a process known as “greenhouse” warming. Another part dissolves into oceans and reacts with water to produce carbonic acid, giving rise to a series of chemical reactions resulting in increased levels of surface water acidity. These two threats, warming and acidification, combine to threaten the survival of coral reef ecosystems everywhere.

Coral reefs are very sensitive to even small increases in temperature. The symbiotic relationship between corals and microscopic algae living in their tissues can break under stress, resulting in the expulsion of the algae. The process is known as “bleaching” since the removed algae exposes the white calcium carbonate skeletons, taking away much of the coral’s color. A healthy coral relies on these microscopic algae for oxygen and essential nutrients, and the breakdown of their symbiotic relationship can lead to death unless the coral manages to replace its algae on time. Although corals do often recover, the frequency and severity of bleaching events worldwide are exceeding the capacity of many coral ecosystems to do so. Regular reports of major global bleaching episodes began in the 1980s. And, the greenhouse effect has been enhanced by natural warming processes like El Niño events, bringing increased temperatures to surface waters of the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean.

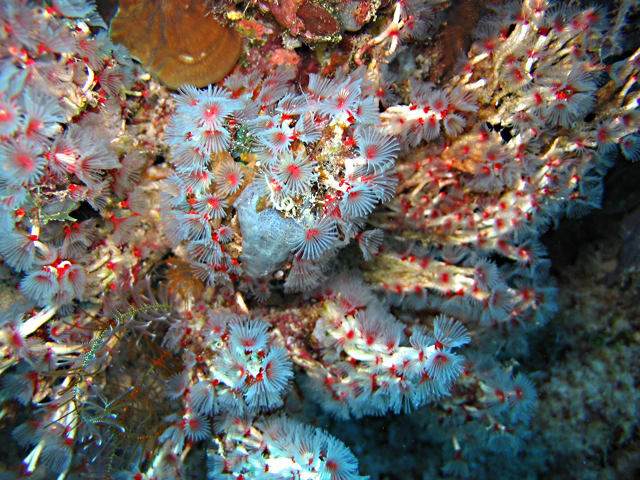

Image courtesy NOAA Dept. of Commerce Photographer David Burdick | Starfish, Mariana Islands, Guam. Thousands of marine organisms depend on coral reefs.

Corals produce calcium carbonate to create their external skeletons (a process called “calcification”), which makes up the physical structures of the reef ecosystem. With oceans absorbing nearly one-half of total fossil fuel CO2 emissions, ocean acidification is compromising the ability of reef-building corals and shell-producing organisms to calcify. While laboratory studies have shown that corals themselves, when exposed to extreme levels of acidification, may lose all their external skeletons and still survive, the loss of the three-dimensional structures of the reef ecosystem would impact thousands of marine organisms that call it home.

Escaping Heat & Acidification

Not all areas in oceans are being affected the same way. Of course, coral reefs cannot escape. Attached to sediment, they will spend their adult lives confined to the same spot where they first landed as larvae. But, while reefs in areas negatively impacted continue to decline, a new generation of larvae, driven by ocean currents, will give rise to new coral colonies, some in regions previously unsuitable. The equator is warmest; thus, it is there that temperature limits for corals will first be breached. As global warming proceeds, corals may be driven away from the equator and into high latitudes. On the other hand, dissolution of CO2 in seawater is facilitated by low temperatures; therefore, effects of ocean acidification are more significant at high latitudes. Acidification will tend to shrink suitable habitat towards the equator. The choice is warming vs. acidification – out of the frying pan and into the acid bath. Does this spell the end for coral reefs?

Recent research suggests that warming may be more of a problem, at least in the short term. Effects of acidification are not yet as strong, and high latitude areas are likely to fare better with the levels of warming expected throughout the next 50 years, even if acidification leads to weaker reef structures. Geoengineering – the deliberate human intervention in the climate system – has been gaining weight in recent years as a last-ditch attempt to avoid global warming. Initiatives focusing on reduction of the amount of sunlight reaching the earth (for example, by release of reflective particles high in the atmosphere) would stop part of the incoming sunlight and create conditions similar to those that may result from a major volcanic eruption.

Such measures could buy extra time for coral reefs and possibly avoid significant habitat collapses that would otherwise take place within this generation’s lifetime. This is particularly true in the equatorial western Pacific where some of the richest coral reef ecosystems are currently found. However, any alteration in a system as complex as the planet’s climate is also fraught with danger, with implications that could be far-reaching and beyond mankind’s ability to fully anticipate. Such alterations also fail to address the root of the problem – the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. While atmospheric CO2 levels remain high, ocean acidification will continue unabated. Ultimately, drastic reductions of fossil fuel emissions may be the best hope for coral reefs.

An Uncertain Future

Image courtesy NOAA Dept. of Commerce | Attempts to protect Earth’s oceans are underway; much work still remains, however.

The divers, running low on air, start the slow ascent to the surface. With images of the bright underwater kingdom they’ve just visited still replaying in their minds, they are blissfully unaware of the drama slowly unfolding beneath the waves. Far beyond an aesthetic loss, the demise of coral reefs represents a large threat to the livelihood of millions of people who rely on them for fishing and tourist income. In addition, many tropical countries benefit from the coastal protection they provide – a last barrier against wave action and the fury of tropical storms. The implications of the loss of so many species from the ocean food web are mind-staggering. But hope still remains. Recent years have brought about a mental shift regarding Earth, the water planet. Initially considered a limitless source of food and a convenient dumping pit for waste, oceans are increasingly starting to be regarded as a delicate and essential piece in the complex machinery that keeps the planet habitable.

A breathing, living world, both land and water ecosystems work together to regulate availability of elements essential to life. With tighter control on fisheries and ocean pollution, and creation of a network of marine sanctuaries that gives marine ecosystem a chance to recover, attempts to protect life’s underwater patrimony are underway. But much work still remains if the divers just leaving the water are to share with their children one day the natural beauty and wonder that is a coral reef.