CH2M HILL Restores “Cuckoo’s Nest” Hospital

The most sustainable projects reach across time and allow people to draw upon what they value most from the past while also harnessing new understandings to create a better future. This philosophy guided a major project at Oregon State Hospital (OSH), the location for the Academy Award-winning film, “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” which both preserved a national historic landmark and transformed it into a model of modern psychiatric care.In the process, a sustainability success story unfolded, and the surrounding community gained a source of pride.

The increasing influence of the approach to combine the best of all eras can be seen in the global trend toward restoring existing buildings – using them in new ways never dreamed of by their original owners. Run-down warehouses now house arrays of high-tech servers, and mothballed factories have become solar panel manufacturing facilities. A recent Department of Defense study found that such adaptive reuse can avoid the energy costs of preparing a new site and constructing a new building. In addition, the “original design intelligence” of older buildings, including heat wells, durable materials and natural lighting and ventilation, can conserve energy and reduce greenhouse gas generation.

Discovering synergies between environment and economy at OSH demonstrated new ways both to minimize ecosystem impacts and to save money. Maintaining outdoor spaces cherished by the community, the project also carried forward the timeless connection between healing and nature.

Respect for an Historic Landmark

The first OSH building in Salem was constructed in 1883 and influenced by the design principles of Thomas Kirkbride, MD, which were meant to facilitate effective psychiatric treatment according to knowledge at the time. The original OSH Kirkbride building had wards for patients that extended symmetrically from a central administration area with small rooms for patient living quarters. Nearly 100 years after it was built, the building was chosen as the location for the Academy Award-winning film, “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” based on the novel by Oregon author Ken Kesey.

Current patients include adults with persistent mental illness, who are considered a danger to themselves or others. The Oregon State Hospital Replacement Project (OSHRP) evolved from the governor’s 2004 mental health task force report on strengthening the statewide mental health system. Planning began in 2005, and in 2006 criteria for site selection were drafted and public outreach began with involvement from many public and private stakeholders. OSHRP gained steam in 2007 when the state’s legislature authorized $458.1 million for a new 620-bed facility in Salem and a 174-bed facility in Junction City, with the Oregon Health Authority as owner.

CH2M HILL became project manager with Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum and Portland-based SRG Partnership jointly selected to design the two sites. Hoffman Construction Company was chosen as general contractor. Renovation of the Salem hospital began in spring 2009. By December 2011 – ahead of schedule and under budget – OSH transformed into a modern “treatment mall” model of recovery-based care.

Photo Courtesy: CH2M Hill

Improved Outcomes with Refurbished Spaces

The impetus for overhauling the OSH Salem campus was to meet current standards in psychiatric treatment while facilitating new approaches to patient care. Prior to OSHRP, care was provided within small living quarters. With such restricted space, staff could work with only a few patients at a time, and it was not easy to customize treatments. Unit-centered care also increased patients’ sense of isolation. Jodie Jones, OSHRP deputy administrator for the project at the time, summed it up by commenting that “the way we wanted to provide services just didn’t work in this building.”

OSH clinicians had been considering how to improve patient care and were intrigued by the “treatment mall” approach. At User Group meetings for the project, they discussed how new facilities could support innovative ways to interact with patients. As a result, a plan specific to OSH began to emerge. This new vision of mental healthcare emphasized normalization, self-determination and reintegration into society. Patients would be encouraged to participate actively in their recovery and to gain practical skills necessary once they left the hospital.

Design of buildings and outdoor spaces would be vital to carrying out this vision. The “house” area would provide living quarters, and in the surrounding “neighborhood,” patients could receive treatment, meals and recreation. The “downtown” would provide access to additional amenities, such as a café, hair salon, spiritual room, fitness and music rooms, and arts and crafts center. At a “bank,” patients could withdraw money and use it in a “market.” Outdoor courtyards, viewed and accessed from surrounding buildings, would provide security without fencing while connecting patients with the healing effects of nature. Engaging, uplifting artwork would help to create a recovery-focused environment.

The design team developed a program that considered a wide range of criteria: how spaces would be used and equipped, how big they would be and what adjacencies would be needed for efficient operations. They discussed how to lay out the historic and new buildings so security, state, staff, patient and community needs would all come together. And, they brainstormed ways to maximize use of the Kirkbride building.

History Meets Sustainability

The OSH campus covers 140 acres with Center Street running east–west through the property. The OSHRP site included only 100 acres south of Center Street. Abutting Center Street, the iconic Kirkbride building had been declared a local historic landmark in 1990. Since 1883, many other buildings had emerged around it. A community initiative resulted in a 2008 National Historic District designation for the entire campus, which occurred a few months into OSHRP.

“Preserving historic buildings can help us orient ourselves in our place in time,” OSHRP administrator at the time, Linda Hammond, remarked.

While the designation greatly increased the complexity of planning and permitting, it also brought new opportunities in sustainability. Constructing new buildings around the restored Kirkbride would capture the value of existing footprints since open space would not have to be sacrificed and new ground would not be broken. Other sustainability advantages became apparent as the OSHRP team sought Silver LEED designation.

Preserving Historic Elements

While some features from yesteryear enhance sustainability, others do not. Preserving the old wavy window glass in the Kirkbride building, for instance, would make some preservationists happy. But, it would also conflict with state energy efficiency design (SEED) criteria that energy consumption should be 20 percent below code. At OSH, special needs for patient and staff safety, maintenance and controlled costs complicated the issue further. However, the collaborative project environment allowed a solution: The original windows visible from Center Street would be restored, thus retaining their old-growth wooden sashes but modifying them to hold insulated glass. Replicated windows would be used on less visible sides of the building.

Photo Courtesy: CH2M Hill

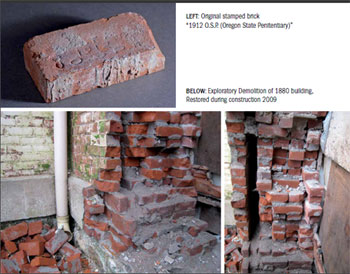

Bricks making up the building’s outer walls also presented sustainability opportunities and challenges. Probably made from nearby mud and clay, they were stamped with “O.S.P.” by their makers at the Oregon State Penitentiary. Exploratory demolition revealed walls made of five withes or vertical sections of one-brick-thick units. An airspace between the four load-bearing inner wythes and outer wythe provided insulation and moisture protection. However, more than 66,600 square feet of outer surface required remediation for lead paint, and the bricks and mortar were degrading. Delicate repairs were made to mortar joints, and the structural integrity of sound bricks was restored while others were replaced.

In 2011, the Kirkbride restoration received the Hammurabi Award of Honor from the Masonry & Ceramic Tile Institute of Oregon with the following commendations from judges: “The completed project extends the life of an irreplaceable landmark so that it meets modern patient care standards. . . . Remarkable; a very challenging project.”

Reducing a Carbon Footprint

The narrow outline of the original Kirkbride design captures the daylighting needed in the 1800s, which today contributes to a more personal, less institutional, feel. Other energy conservation measures include occupancy sensors, energy-efficient lighting fixtures and high-efficiency boilers, chillers and water heaters. Throughout the facility, the HVAC system has air handlers with efficient fanwall technology, and the patient wings have heat recovery wheels. All systems are run by an efficient sequence of controls. The building is consuming a remarkable 56 percent less energy than code requirements, thus reducing its carbon footprint by more than one-half – great for operating costs and the environment.

Natural ventilation and an active chilled beam system made of copper piping bonded to aluminum fins are used for cooling. This innovative system allowed for the smaller mechanical units needed due to space restriction in the historic roof. More than 90 percent of materials removed during demolition were reused or recycled. Demolition brick materials were crushed and re-used as backfill. Recycled materials were used to fill old subterranean tunnels; wooden structural members, such as massive old-growth beams, were preserved or recycled.

Seeking to invest in the community and reduce environmental and financial costs for transportation, the OSHRP team also adjusted the renovation plan to replace 16-inch bricks with 12-inch bricks from a local manufacturer. This provided a boost to the economy through local procurement.

A Natural Connection

After the historical significance of existing buildings was assessed, the OSHRP team discussed how best to locate and design the new hospital complex. The team decided to keep the oldest portion of the Kirkbride building, six cottages (formerly used to house hospital staff) and several outbuildings. Hammond explained that “the decision was not as simple as what to demolish and what to preserve or mothball, but what could be revitalized and reused.”

Photo Courtesy: CH2M Hill

The team worked closely with preservationists and walked through the site with them, making more than two dozen applications to the Historic Landmarks Commission. Considering aesthetics, architects identified themes in original materials and elements that new buildings could echo. New buildings along Center Street would use similar massing to create a visual rhythm reminiscent of existing buildings valued by the community. The park-like grounds to the west of the hospital were another treasure restored. Containing more than 570 trees, this area was often used by community members. Children played, joggers ran, and dogs with their owners strolled along the paths while patients also walked the grounds. Community members were adamant that no green space be sacrificed for new buildings. Incorporating their ideas helped carry forward Kirkbride’s belief that connection with nature was crucial to recovery. At the southern boundary of the OSHRP site, where stormwater features had been planned, more than two acres of wetlands were identified. More wetlands were mapped where a new access road was planned. Careful grading, design refinements and a modified road alignment minimized wetlands impacts.

Soft on People

Like all projects, OSHRP involved schedules, budgets, contracts and communications. Managing such components was especially challenging because of the project’s complexity. But the greatest contribution of the project management team was its focus on people. With strong support from the Oregon Hospital Association, an environment for collaboration was established. “Project first thinking” meant putting what was best for the project – ultimately, for the patients – at the forefront of any decisions.

That is where the project management mantra, “tough on issues, soft on people,” came into being. For the project to succeed, each member of the team would need to succeed. Under those conditions, people take risks and generate their best ideas; problems get solved, and conflicts reach resolutions satisfactory to all.

OSHRP achieved the right balance between people and project. “All of the entities stepped up and were willing to work together,” said Jones. “It was the team that made it such a great project.” Establishing the right working environment paved the way for the success of all. Establishing clear project procedures was also key. With processes covering all phases carefully described and responsibilities defined, the stage was set for stellar performances.

This collaborative environment was critical as the project stretched everyone involved. With more than 1,300 patients and staff on campus, one of the many logistical hurdles was maintaining operations during construction. Patients were housed on both sides of Center Street, but the heating plant and food service were on the south campus only.

A construction phasing plan used details of the 50-plus campus buildings to coordinate patient and staff relocations, services, demolition and construction. Remodeling six of the cottages along the site’s western boundary provided housing during construction for 36 transitional patients, thus saving $20 million and leaving behind a permanent housing asset. Painted with colors used in the early 1900s, renovated cottages received rave reviews from patients, staff, patient advocates and legislators. “With all of our partners working together to find a way to continue operations while building, we saved money for the state,” Jones said.

Community Engagement

OSHRP grew out of a complex network that included global developments in sustainable practices, psychiatric research results, state and federal regulations, and community needs. At the local level, Salem community members expressed a range of concerns about the proposed project, including what effect construction would have on Center Street business.

Photo Courtesy: CH2M Hill

The OSHRP team addressed this concern by rallying the roughly 800 construction workers to patronize nearby shops, such as the Fresh Start Market and Espresso, where juvenile offenders learned useful skills and received a second chance to fit in and contribute.

When homeowners across from the cottages worried about exposure to dangerous patient behavior, the project team attended community association meetings and walked around the neighborhood handing out fliers, thus establishing rapport and building relationships. “We worked hard to introduce those neighbors to the patients, so they would understand that transitional patients would not be a threat,” said Jones.

“We wanted them to know what the patients were like and how the system would operate.”

Gifts to the Future

Embedded in history but newly invigorated, OSH buildings and grounds have a grand presence because this is an important place with important work going on inside. The new hospital preserves historic, cultural and environmental resources for future generations while reflecting Oregon’s commitment to continually improving the mental health system to serve Oregonians now and into the future. Like a healthy ecosystem, various parts all work together and link patients to the natural environment and surrounding community to its past. The lessons learned and techniques developed will be carried through to the Junction City hospital project. Beyond Oregon, OSHRP stands as a testament to what people working together can do to prove that sustainability pays.