Empowering Women in Tanzania

Women entrepreneurs are increasingly recognized for the success of their businesses and for the important contributions to their countries’ economic well-being. A growing body of research indicates that women’s economic empowerment is positively correlated with improved family welfare and nutrition, higher education levels for girls and improved economic growth for society as a whole. Yet, the African continent contributes less than 2 percent of global income, and, as a result, most of its citizens remain mired in poverty. The incidence of poverty among women, as well as its depth and women’s vulnerability, is particularly marked in Sub-Saharan African countries where women often encounter more obstacles in starting and sustaining businesses.

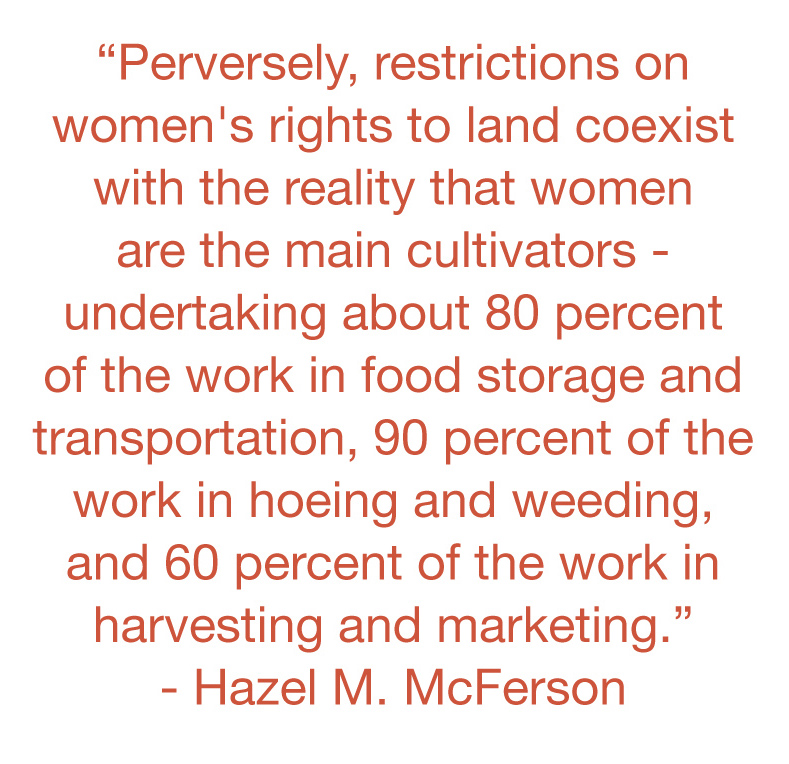

Causes are numerous, including traditional restrictions on women’s property rights, weak governance and violent civil conflict in perpetuating gender discrimination and poverty. Women face many barriers to economic participation while their contribution to economic activity and development is substantial. Country veterinarian Victoria Kisyombe, DVM, created SERO Lease and Finance Limited (SELFINA), an indigenous Tanzanian enterprise, to overcome barriers that social norms and customary law often impose on women entrepreneurs in this East African country.

“The challenge is access to finance, simply because women don’t own property,” said Jacqueline Maleko, co-founder of the Tanzania Women’s Chamber of Commerce. “They’re supposed to provide collateral, but due to social and cultural norms and values of African societies, most of the time women don’t own such properties. So, this becomes a big challenge in accessing finance.”

The consequences of weak property rights are clearest when marriages terminate. As a result of divorce or widowhood, women in most African countries are often stripped of the right to use their husband’s land, which they may have tended for years, thus losing their main source of income. The cycle of poverty is intensified when the former couple’s children must withdraw from school to find work, thus compromising their economic future.

Finding herself in precisely these circumstances upon her husband’s death is what motivated Kisyombe to launch a business to provide women entrepreneurs – specifically micro-entrepreneurs in rural Tanzania – with the financial support necessary to create and to sustain business. Although her personal experience opened her eyes to a new world of widows left without land or significant assets, she soon offered her business services to all women entrepreneurs, widow or not.

Kisyombe did not intend to be in the financing business. But, being a compassionate person, she exchanged her loss for a positive cause and engaged her heart, mind and soul in service to other women so they could, collectively, make a difference. The urgency was clear since women were expected to help support their families even though they had virtually no employment opportunities, particularly in rural areas. As a result, small enterprises like selling produce, groceries or other items were often the only alternative. However, women lacked access to even the most basic assets for business success, to include productivity-enhancing technology.

SELFINA, www.selfina.com, was incorporated in April 2002 as an indigenous Micro-Finance Institution (MFI) to assist women in building a solid economic base. Specializing in lease micro-finance, the organization creates opportunities, provides resources and promotes self-esteem for its clients. A leading pioneer in micro-leasing in Tanzania, SELFINA offers a credit window exclusively for women and focuses on two products: (1) leasing equipment on a financial, rather than operational, basis (where the lessee has the right to ultimately own the assets), and (2) buying women’s equipment when they need liquidity, then allowing them to keep the equipment on lease, known as “sale and leaseback.” SELFINA has positioned micro-leasing as an effective and practical way to negotiate around the problem of lack of collateral and to increase access to finance for women.

“The problems are diverse,” noted Kisyombe. “Women are oftentimes breadwinners for large, extended families. Although they play an integral role in the rural economy, they cannot obtain equipment to maximize their income.

One needs collateral in Tanzania to obtain assets, which, for the majority of Tanzanians, can only consist of land.

Women are largely uneducated about the need to obtain official deeds for land that may have passed down between generations. Thus, when the time comes to use the land as collateral, women seldom have a way to

prove ownership.”2

Tanzanian women entrepreneurs face many challenges. A 2003 International Labor Organization (ILO) study shed light on gender-related constraints in Tanzania, including (1) difficulties in accessing bank finance due to lack of property rights (collateral), (2) underestimation by bank officials of women’s capacity to borrow and repay, (3) time pressures due to multiple caring roles at home, in the community and in the business and (4) women subject to pressure by corrupt officials to give sexual favors. For example, even when women legally own property, cultural values may not allow them to pledge this as collateral as they still have to secure permission from family members. Findings also state that while men can be supportive to women entrepreneurs, husbands can present a serious hindrance by underestimating their spouses’ capabilities and, hence, by discouraging them from taking risks and developing substantial enterprises.3

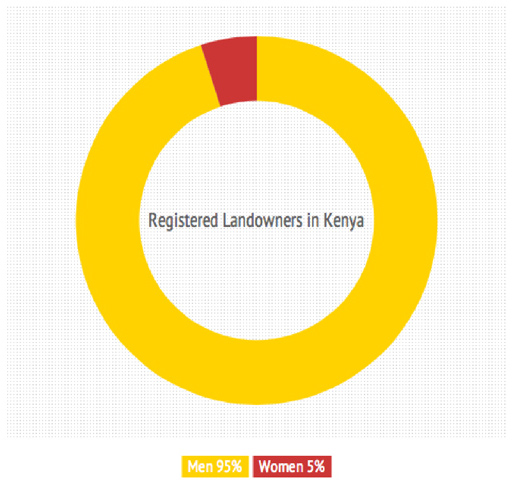

In fact, several African countries, including Tanzania, have promulgated legal statutes to address women’s lack of land rights. However, these laws have been largely ineffective either because they have deferred to customary law or have simply not been enforced. For example, while Kenya’s constitution outlaws gender discrimination, it also upholds customary law on marriage, divorce and inheritance. In Tanzania, two land acts invalidate customary laws that exclude women from property ownership. But, they are not fully implemented in part from lackadaisical enforcement by male-dominated judiciary and in part because women are not aware of their legal rights.3

The Tanzanian government has shown some leadership in this area compared to its neighbors Kenya and Uganda. Various constitutional and legal provisions in Tanzania seek to ensure equality for women by providing formal protection against discriminatory, customary laws. The Village Land Act invalidates customary laws that discriminate against women and recognizes a wife’s rights to land upon the death of her spouse or divorce. Moreover, since 2002 Land Tribunals are required to include at least 43 percent women.

But despite these positive legal provisions, customary norms still dominate decisions on land ownership. In Tanzania, customary law protects against alienation of land outside the clan. It can prevent women from inheriting land, if male heirs exist, due to fear that land could transfer outside the clan through marriage. If widowed, women can also be denied the right-of-residence on family land. As a result, customary laws of inheritance and cultural norms have meant that few women, in practice, have inherited land.

“When I needed land, my brothers refused to give it to me because I was married. In my culture a woman has to be a vessel and respect her wifely, motherly and grandmotherly duties. Women are not expected to own property and, in most cases, husbands are very jealous of their wives doing business,” according to Khadija Simba, owner of Kay’s Hygiene Products.4

Upon SELFINA’s inception, Kisyombe knew not to overstretch its operations. As managing director of the company, she brought in experts in women’s advocacy, law, accounting and finance as her staff. Together they developed a rigorous framework with specific metrics to assess applicants and to estimate the monthly payments they would be able to meet, thus determining the maximum size of each contract. The organization also entered a wide variety of industries tailored to a diverse set of women entrepreneurs, including cooling, machinery, transportation and livestock. The business plan worked, and SELFINA became a huge success. Moreover, that success had a multiplier effect. With more women repaying their leases, institutions were more willing to provide money to SELFINA – and the more money it had, the more it was able to lend.

Leasing Instead of Micro-Credit

As their businesses grow, many micro-business owners would like to purchase new machinery from a micro-finance institution (MFI) because it can hold the key to increased production. However, MFIs often are not able or willing to lend for the longer periods of time that machinery requires. Long-term financing from other sources is usually not feasible as banks and leasing companies require collateral, a well-documented credit history and financial statements. For many micro-businesses, leasing provides an effective alternative to taking on more debt.

SELFINA evolved from financing just a few dozen clients in 2002 to more than 200 in 2004. With a 98 percent repayment rate, demand for its products skyrocketed. Then the real wave hit: In less than five years, between 2004 and 2009, SELFINA increased its client base to more than 16,000 contracts. Portfolio volume grew by more than 600 percent, and by the end of 2008, it was TZS 7,000 million (Tanzanian Shillings) – about USD $5 million.

“The foundations we initially established were critical in guaranteeing the company’s future,” noted Kisyombe. “It was a highly professional approach that focused on mutual business benefits for SELFINA and the lease holder. . .”5

An enterprise that provides a needed service, genuinely cares about the well-being and success of its clients, contributes to food security and provides stability for a family and community is more sustainable than aid and development assistance. Since 2002, SELFINA has achieved the following:

– Economically empowered more than 25,000 women, impacting more than 200,000 lives through accrued benefits;

– Enhanced productive capacity and increased incomes and employment among poorer women in Tanzania in a sustainable manner. SELFINA aims to impact more than 440,000 individuals by 2014;

– Generated self-employment and created jobs for others. Women are now proud owners of their own businesses, and more than 125,000 jobs have been created;

– Changed attitudes about business leading to maximizing opportunities and strengthening small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Some of the women have grown from managing subsistence micro-businesses to running mainstream small- and medium-sized businesses;

– Increased education as women are sending their children to school;

– Helped to create sustainable and secure micro-businesses;

– Encouraged women to have greater self-esteem. They love themselves more and are, thus, able to spread that love to others. They are “paying it forward” by mentoring young women;

– Increased, in some instances, the strength and equality of existing marriages as husbands participate in their wives’ business opportunities.

SELFINA has delivered exactly what a successful financial product is supposed to deliver – allowing people to acquire or, in this case, to borrow equipment essential to their business that would have otherwise not been accessible. It has given women, and widows in particular, a chance to be economically viable while realizing a dream of entrepreneurship and self-sufficiency. But beyond this, the SELFINA staff show caring and compassion for their clients as they take every opportunity to coach them towards success.

“I am constantly thinking of ways to grow the vision and myself,” said Kisyombe. “Getting funding is important, but getting proper training for our staff and clients is also vital. . . . Innovation continues to be a strong driver of our performance. . . . we want to give our clients the tools to be successful, not just leave them to figure it out alone.”5

Several women clients mentioned that doing business has improved their societal status. They have achieved a more equal status in their home with their husbands, giving them more say in family decisions. A Tanzanian rice farmer near Mbeya says she now makes business plans with her husband because she is the SELFINA equipment lessee. She is able to make a significant financial contribution in everything they do. In fact, she is contemplating leasing a larger tractor to expand their rice harvest. As a result of their business success, they are able to send their sons to boarding school. (No secondary school exists in their town.)6 They have also improved their domestic circumstances with home improvements like an indoor toilet.

Kisyombe’s minister, Reverend Ernest Kadiva, explains: “Dr. Kisyombe has inspired me in many ways. Being a widow, you might expect her to be down, but she is not a depressed woman at all. She is so courageous – always doing things to support women and to encourage others to work harder, to get rid of poverty, to share with women and to encourage them. That’s how she inspires me.”7

Image courtesy Sandra E. Taylor, JD, CEO, Sustainable Business International | Victoria Kisyombe, DVM and founder of SELFINA

Speaking of the future, Kisyombe said, “What keeps me going is when I see what we’re able to do – how it translates in the life of other women when I see their children, when I see their eyes open up when they say ‘asante.’ (Swahili for ‘thank you.’) I don’t need to be given asante; but you see they are happy; they are growing, and some of them are even diversifying into other businesses. That you cannot put into simple words; it’s here in my heart. You change lives; you touch peoples’ lives. It’s everything that goes with that, which makes it all worth the giving, the time that you give. Sometimes even your family forgets, given all the time I put into this, that you really want to do it. As I’ve said time and again, it’s really rewarding.”8

SELFINA is a remarkable achievement. This is especially true when one considers that little works in many developing countries in terms of delivering access to finance and economic empowerment to the poor. Previous attempts to deliver credit, through state-run banks for example, collapsed in the face of widespread corruption and defaults. However, many see micro-leasing as much more than a financial instrument. It has been suggested that it has the potential to be entirely transformative. An influential view argues that by putting more spending power in the hands of poor families and, perhaps more importantly, in the hands of women, micro-credit and micro-leasing can expand investment in child health and education, empower women in their homes and reduce discrimination against them.

SELFINA wants to bring about not only economic but also social change. It wants women who have long suffered as second-class citizens to be allowed to make a better quality life for themselves and their children. In turn, their empowerment can build healthy families, a dynamic community and a stronger nation.