Evolution of SROI on DoD Healthcare Projects

President Obama’s October 5, 2009, Executive Order 13514 entitled, “Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy and Economic Performance” puts the onus on government entities seeking project funding to articulate their case using metrics that provide a full accounting of all social, economic and environmental impacts. While the importance of these issues is widely recognized, agencies are challenged when they try to integrate sustainability into their mission and operating decisions. This task is particularly challenging because traditional life-cycle cost tools look only at direct cash benefits, ignoring social and environmental benefits. A handful of Department of Defense (DoD) hospital projects have turned to the Sustainable Return on Investment (SROI) analysis framework to help make the necessary sustainable building decisions based on a far expanded knowledge regarding the full impact of their choices.

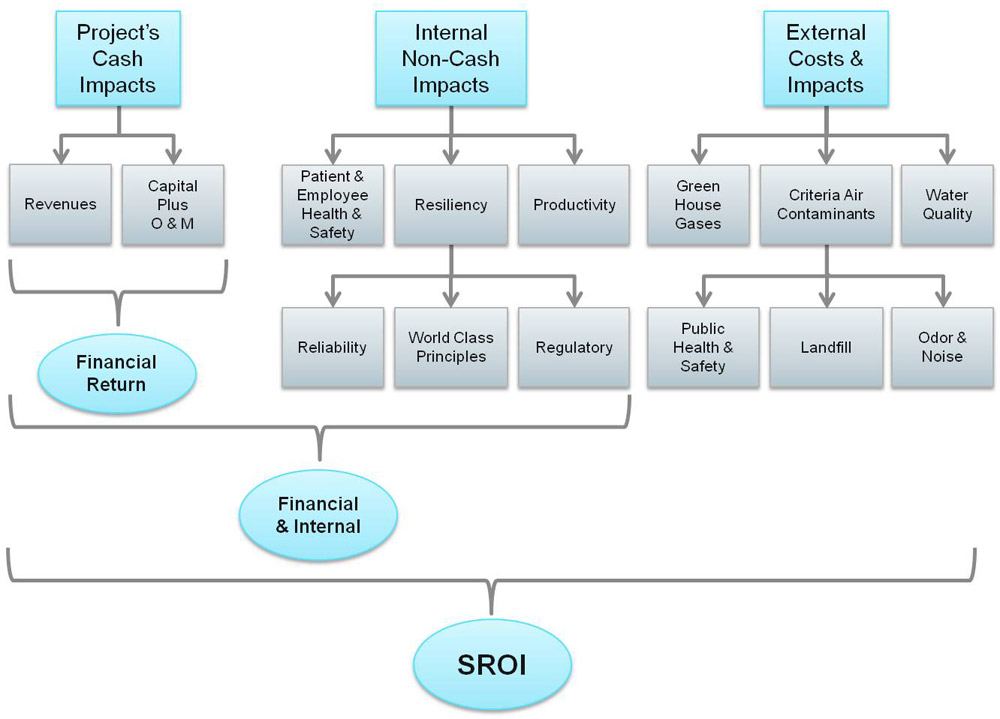

The SROI process monetizes social and environmental impacts related to projects. It also provides the equivalent of traditional life-cycle cost metrics, called Financial Return on Investment (FROI), in its analysis. FROI accounts for internal cash costs and benefits only while SROI accounts for all internal and external costs and benefits of the triple bottom line in dollar terms (i.e., greenhouse gas emission impacts or the social cost of water saved). Other relevant incremental social and environmental impacts include air quality, water quality, waste reduction, human health and labor or productivity costs. The process follows a transparent methodology that obtains data, validates alternatives, assigns risk and probability, and communicates decision rationale. The modeling framework compares the social and financial benefits of the alternatives in relation to their costs for design, capital, replacement, and operating and maintenance. Additionally, SROI is fully compliant with federal sustainability mandates.

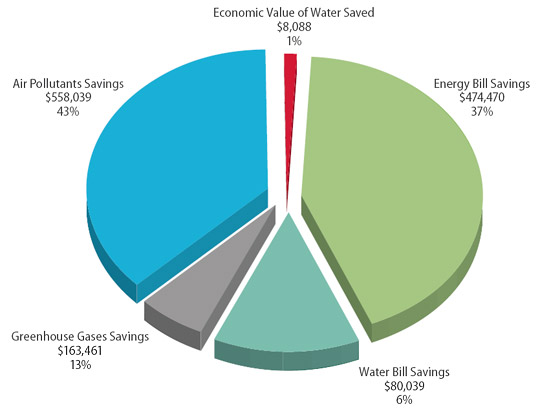

In 2008, SROI conducted on the first hospital, the 1.2 million-square-foot, LEED-registered Fort Belvoir Community Hospital in Fort Belvoir, Va., provided a clear distribution of benefits associated with project solutions, such as economic value of water saved, air pollutants savings, greenhouse gases savings, water bill savings and energy bill savings. SROI analysis was useful for reporting results; however, since it was incorporated mid-project, the full potential of the model could not be leveraged in early decision-making.

Image Courtesy of HDR|Ft. Belvoir Distribution of Benefits

The following diagram highlights how SROI incorporates not only the cash impacts to a project but additionally monetizes the internal and external non-cash benefits. Fort Belvoir included not only traditional cash inputs but also more esoteric inputs, such as quantifying environmental savings from reduced carbon emissions and the social cost of water saved.

Image Courtesy of HDR |SROI Process Diagram

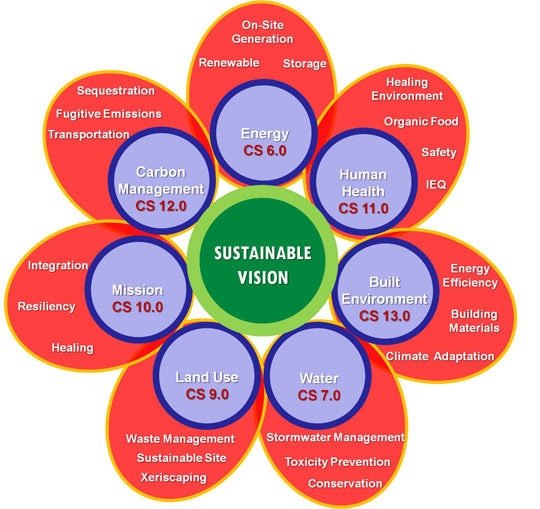

The most recent evolution of SROI methodology was used in the decision-making process for the 1.1 million-square-foot, DoD pilot for LEED for Healthcare, Fort Bliss Replacement Hospital. SROI created a decision-making tool that evaluated and assessed sustainable design and evidence-based design alternatives during each design phase so only the most efficient, synergistic and cost-effective combination of initiatives would be included in the project.

Through a collaborative effort, project architect HDR Inc., the Health Facility Planning Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Fort Bliss and the U.S. Army Medical Command (MEDCOM) analyzed a number of policies when alternatives for Fort Bliss were identified. These included federal, Department of Defense, Army, Medical Command and Fort Bliss policies along with third-party goals, such as LEED, the Military Health System’s world-class and Evidence-based Design principles and USACE directives.

Image Courtesy of HDR|Ft. Bliss Vision Diagram

During the project kick-off, the integrated project team developed a Master Sustainable Strategy Tracking List with 75 sustainable design alternatives across the categories of site, energy, water, indoor environmental quality, materiality, evidence-based design, regionalism and innovation. These design alternatives supported the project’s sustainable vision, focusing on long-term goals for 2020 and beyond to meet federal sustainable mandates and LEED, and crossed design phases from concept through construction documents and into construction and operations.

At a two-day visioning workshop, the team focused on measuring the design alternatives from a life-cycle cost perspective rather than the typical first-cost perspective. Work flow centered on creating data (culled from the fields of sustainability, science, environmental management and systems thinking), which was customized for the Federal government. Additionally, data was created for each project component: master site, hospital, clinics, administration building, clinical investigation building and central utility plant. The SROI reporting structure allowed the installation to look across a facility portfolio and compare buildings according to specific levels of performance. This is in contrast to LEED and other green building rating systems that focus on comparing a building to a baseline measurement.

Metrics included:

- Energy Use Intensity – energy use per square foot per year

- Carbon Intensity – metric tons of CO2 per square foot per year

- Water Use Intensity – water use per square foot per year

A “dashboard” was created to summarize data and to provide a snapshot of decisions needing to be resolved. The tool (modeled after financial and investment dashboards, such as Yahoo! Finance) categorizes information into three sections:

- Economic Costs and Benefits

- Architecture and Engineering Analysis

- Recommendations and Path Forward

The project team then narrowed the sustainable design alternatives necessary to inform the schematic-level design to ensure decisions were not only made early but also that they would reduce energy consumption, transition to renewable energy, reduce potable water use, divert waste from the landfill and improve health outcomes. The result produced 15 discrete sustainable design alternatives in these areas:

- Thermal storage and co-generation;

- Heat-recovery chillers, energy recovery of ventilation air and ground source heat pumps;

- Solar hot-water heating, solar photovoltaic systems, geothermal direct heating and heating, ventilation and air conditioning exhaust energy recovery wind turbines;

- grey water and wastewater reclamation, treatment and reuse, and dishwasher water recovery and reuse;

- recycling station; and

- HEPA filtration and hydrogen peroxide vapor cleaning.

Image Courtesy of HDR |Fort Belvoir Community Hospital

The 15 initiatives were placed into five paths, water, waste, evidence-based design and two paths for energy to allow for a systems approach to sustainability. The energy paths were created by placing compatible items like thermal storage and direct deep geothermal together. Both energy paths were then re-evaluated as sustainable systems using SROI to formulate a value-based comprehensive approach to sustainability.

During the S-4 Design Development Phase, Path One was deemed the best investment based on comparable output metrics from an SROI standpoint. Energy Path One will create an energy-use intensity reduction of more than 60 percent and will pay for itself in 28 years from a discounted cash perspective. The benefits accruing to this alternative include cash and social savings from reduced energy and natural gas use. As a result of reduced energy-use, social savings from greenhouse gases, criteria air contaminants and nuclear power account for roughly $3 million throughout the study period.

One of the tertiary benefits is the level of thought that goes into the SROI model. The model inputs require a thorough level of thought that can expose the “ripple effects” of decisions, positive and negative. In the case at Fort Bliss, it helped identify the benefits as well as the potential risks related to a deep geothermal initiative.

The Fort Bliss hospital results demonstrate that SROI ensures greater rigor in the decision-making process and creates a defensible position for the project. By involving all stakeholders in the SROI process, each team member is an integral part of the process, resulting in improved collaboration, increased transparency and a greater level of consensus achieved earlier in the project. Above all, SROI results in a better final product and more responsible investments of taxpayer money.

Executive Order 13514 tasks agencies to develop strategic sustainability plans, report progress transparently and ensure full accountability for achieving goals. The SROI framework allows agencies to comply with Executive Order 13514 while justifying their expenditures in sustainable initiatives to stakeholders, articulating the merits of proposed initiatives to funding agencies and building confidence in their commitment to sustainability.

Given recent policy changes with DoD that are requiring more cost justification for application of sustainable strategies, application of cost-benefit tools like SROI are becoming even more important in the effort to maintain their historic support to high-performance and healthy buildings. It is possible that without these tools, common and effective sustainable strategies will no longer be acceptable.

Note: SROI originated from a Commitment to Action by HDR to develop a new generation of public decision support metrics for the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) in 2007. SROI was developed with input from Columbia University’s Graduate School of International Public Affairs and launched at the 2009 CGI annual meeting. Since then, the SROI process has been used by HDR to evaluate the monetary value of sustainability programs and projects valued at more than $10 billion.