TIBET, Culture at the Edge: Devotion, Development & Climate Change

Itook my first trip to Tibet in 1994 to collect interviews and portraits for my book Tibetan Portrait: The Power of Compassion. When I returned in 2009, I could barely believe the amount of development that had happened. When I flew to Lhasa fifteen years before, my 737 from Katmandu was nearly empty. This time I arrived from Beijing on an Airbus 330 with every seat filled! The road from Lhasa’s new modern airport was now paved and went through a new tunnel and set of bridges that cut 45-minutes off the trip. As I approached Lhasa, the highway divided. What I remembered as a rough two-lane road, which ran through town and hosted an occasional vehicle, was now a six-lane highway full of taxis, SUVs, trucks and buses. Other than the Potala Palace that loomed above the town, I hardly recognized any of the buildings.

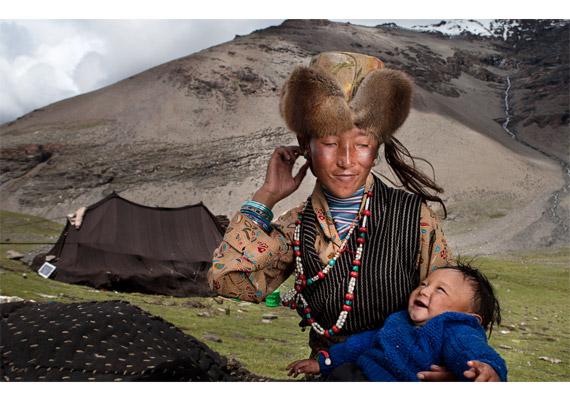

Beginning in 2000, China embarked on what they called the “Western Development Strategy” with the stated aim of building infrastructure to improve people’s lives and protecting the environment. The rate at which this infrastructure has been built in Tibet is nothing less than astonishing. The train, which began service in 2006 and traverses the high and rugged Tibetan Plateau from mainland China, now carries millions of passengers per year to Lhasa. Countless tunnels, paved roads, airports, mines and dams are transforming the Tibetan landscape. All across the plateau solar-powered cell towers provide ubiquitous cell coverage. Even many of the very remote Tibetan nomads now have cell phones, TVs and motorcycles.

Today Tibet is the number one tourist destination in China. In 2009, the majority of the 5.5 million tourists visiting Tibet were Chinese – a 150 percent increase from the year before. Because of the rising popularity of Tibetan Buddhism worldwide and Tibet’s thriving tourism industry, monasteries that were destroyed 50 years ago during the Cultural Revolution are being rebuilt and upgraded. Some are new multi-million dollar structures financed by donations from Hong Kong and the West. Streams of tour groups now flow through the more popular destinations and monasteries every day.

Adding to all the changes that have taken place in the past fifteen years, the effects of climate change are accelerating on the Tibetan Plateau. With an average altitude of 14,000 feet, the Tibetan Plateau is known as “The Roof of the World.” It has also been called ‘The Third Pole” because, next to the North and South Poles, its glaciers contain the largest volume of fresh, frozen water on earth. More important, it is known as “The Water Tower of Asia” because rivers flowing out of those glaciers supply nearly one-third of the world’s population with water. Due to the combination of high altitude and low latitude, the Tibetan Plateau as a whole is heating up twice as fast as the global average, and the glaciers are disappearing at an alarming rate.

Phil Borges|Flooded pastureland due to the rapid and accelerating glacial melt. Shannan Prefecture

In northern areas thousands of lakes have dried-up and deserts have grown to cover nearly one-sixth of the plateau. However, in the southern areas accelerating glacial melt has led to swollen rivers and much flooding. Almost all the nomads and farmers I met complained about decreasing grasslands for their animals and erratic weather patterns that made timing the planting of their crops almost impossible. I photographed several nomads next to the remains of glaciers they had lived near their entire lives. Returning to their summer grazing lands each year since they were children gave them a unique perspective on the accelerating pace of glacial retreat. Many of these glaciers had shrunk to a fraction of their former size in just a few decades.

The nomads and farmers on the Tibetan Plateau are truly the “canaries in the coal mine” with respect to climate change. The Chinese government, realizing its vital water supply is being threatened, has responded to the climate crisis by moving tens-of-thousands of nomads into resettlement camps and fencing off large portions of land in hopes the desertification will be reversed and the grasslands will regenerate.

The looming catastrophe they portend will become all too evident as the glacier-fed rivers begin to diminish and leave millions or even billions of people downstream without enough water. Along with acute water and electrical shortages, experts predict a significant drop in food production, widespread migration of “ecological refugees” and conflicts between Asian powers. Even though scientists disagree on how fast this will occur, all agree it is happening.

In 2007 China made an unprecedented commitment to education by mandating all children attend school through Grade 9. Throughout Tibet small village schools are being closed in favor of larger, more standardized boarding schools. Because of the long distances of most rural families from the new schools, many children will only be able to visit home a few times per year.

Phil Borges|Desertification of former grasslands. Nagari Prefecture

The Tibetan community has met China’s historic investment in education with trepidation. In October 2010 thousands of Tibetan students took to the streets in non-violent protest over the recent decision of the Chinese government to have all textbooks written in Mandarin. For the Tibetan people, it was seen as another step, along with Chinese immigration, in the steady marginalization of their people and culture. They fear when their language dies their culture, with its spiritual practice that has developed over centuries, will disappear. After the recent student demonstrations, the Chinese government indicated they were willing to sit down and discuss concerns voiced by student protesters. It is a least a start in dealing with this centrally important and complex issue.

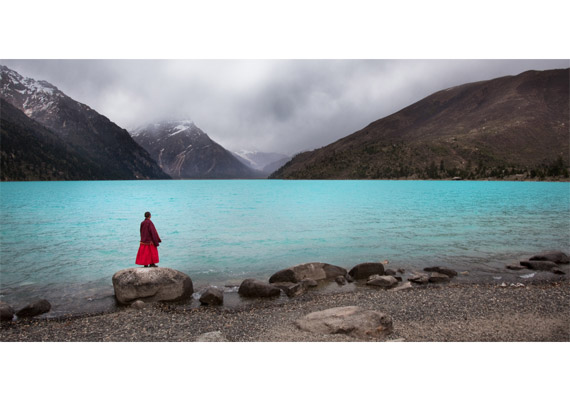

In spite of massive changes occurring in Tibet, the devotion of the Tibetan people to their Buddhist practice appears as strong as ever. The number of pilgrims making their way to their sacred sites – like the Jokhang Temple and Mount Kailash – have actually increased in the past two years. In the mornings and afternoons I watched thousands of Tibetans, even elders crippled with bad hips and knees, making their daily walks around stupas, temples and mountains, spinning their prayer wheels and chanting their mantra, “Om Mani Padme Hum.” For the Tibetan Buddhist, peace of mind is a fundamental lifetime goal. They are taught to value contentment and mental peace above all else since one’s state of mind is believed to be the only possession that survives from one lifetime to the next.

Devoting time to acquiring wealth, fame, status or power in order to find peace and fulfillment is considered very ineffective. They believe lasting peace of mind can only be achieved by paying close attention to and taking control of their motivations. They consider the motivation responsible for most dissatisfaction and suffering to be “self-grasping.” Referred to as “the greatest enemy,” this attitude is rooted in ignorance – ignorance that leads us to see everything – ourselves, others, all phenomena – as separate. It keeps us from realizing everything is actually very interdependent and connected, and that our well-being depends upon the well-being of everything and everyone around us.

Phil Borges|Prayer flags surrounding the Kora (path) around the Princess Wencheng Temple. Qinghai Province

Tibetan Buddhists believe there is no greater vehicle than compassion and forgiveness to counteract suffering caused by the self-grasping attitude. This attitude is slowly dissolved throughout lifetimes by the cultivation of compassion. Devotion to this daily practice is seen everywhere. For example, “Om Mani Padme Hum” – the mantra believed very effective at transforming the mind from self-grasping to compassion – is everywhere. It is found embedded in millions of prayer wheels, carved in countless stones, printed on prayer flags covering mountainsides and emanated from the lips of Tibetans as they perform their daily tasks. If there is one characteristic that defines the Tibetan people for me, it is their open, friendly and joyful nature. It is a testament to their practice.

The Tibetans could undoubtedly benefit from the massive investment the Chinese have made in schools, hospitals, communication infrastructure and roads in Tibet. Since Tibet is China’s number one travel destination, it seems the Chinese people could certainly benefit from experiencing the true Tibetan culture and working together to see it survive and thrive. Ideally these two cultures will be able to stand back from the distrust that divides them to see the benefits that could come from respecting each other’s strengths and values.

Within this article are glimpses of these remarkable people, who live in one of the most fragile environments on earth and who face a rapid induction into the 21st Century while trying to retain that which they hold most dear – their Tibetan Buddhist practice and culture.

Phil Borges|Puchen, age 37, remembers the Nojin-Kangtsang glacier

reached his tent when he was a boy. Shigatse Prefecture

Phil Borges’s TIBET: Culture at the Edge Slideshow