Water for Everyone Forever: A Human-Needs Business Model

This is the story of how $150,000 in corporate dollars from CH2M HILL became potable water for 4,384 high school students, sanitation facilities for 6,325 people, career training in water maintenance for 114 young men and the creation or refurbishment of 53 water points that serve more than 13,000 people. Everyone Forever is the mantra of Water For People, which means every family, school and clinic in the non-profit’s targeted districts has access to improved water supply, sanitation and health services, and hygiene education. One of Water For People’s operating countries is India, where the organization has targeted six districts in West Bengal, one district in Bihar and pilot sanitation programs in urban areas.

According to the World Bank, approximately 50 percent of India’s 1.24 billion people still lack access to basic sanitation facilities and 32.7 percent fall below the international poverty line of US$1.25 per day. This lack of access to sanitation facilities and healthy water systems diminishes opportunities and perpetuates diseases from contaminated water. For example, some schools cannot meet basic human needs because of an inadequate number of urinals and latrines, lack of running water for hand washing, a poor maintenance system and absence of facilities for menstruating girls. In some instances, menstruating girls had no option other than to stay home from school.

Water For People could construct new facilities at a school or provide water wells in a community, but the vision of Everyone Forever requires a different approach. Funding an initial project is simple, but then what happens? Who maintains the water supply later? How are repairs funded? Who has the expertise to conduct repairs, and is this a sustainable profession? How does the next generation carry on the knowledge of these systems and improved hygiene? What role can government play in assuring improvements last?

Water For People has developed a sustainability model for international development, which engages local governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the private sector and residents of local villages to create durable structures that assure water will continue to flow. This process has been applied to an innovative program in West Bengal that begins with an intervention of funding and support, and ends with a gradual withdrawal of external funding as skills and local funding mature into self-sustaining community ownership.

Sustainability Begins with an Exit Strategy

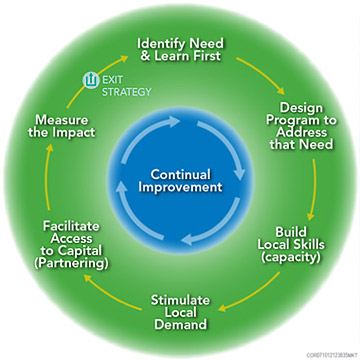

The model for sustainable international development support begins with the end: The ultimate goal of the project is to empower people to take care of their own needs and to create a local environment that drives and sustains itself. The first steps of intervening are to identify the need, to learn how the community functions and then to design a program to address that need. The next few steps involve advocacy – creating a self-sustaining structure by giving people the skills they need to run the program, injecting funds from outside entities to get started, stimulating local demand for the project and then facilitating access to capital so external contributions are not required. Finally, the impact of the project is measured.

Continual improvement is a core concept to ongoing refinement and implementation of the model. To be successful, the program needs to establish goals to gradually withdraw resources while measuring effects of positive change and impact on health, social and economic factors within communities.

© CH2M HILL | A sustainable model for humanitarian aid involves planning an exit strategy up front and driving

each of the steps towards that goal.

To evaluate how this model is working in India, a team of four World Water Corps® volunteers traveled to West Bengal in March 2012 on a technical service assignment. Their tasks were to evaluate Water For People’s long-term water pump repair and maintenance program, to conduct a needs assessment and to look at gaps, areas of concern and areas for improvement. The team included David Strand and Jeff Friesen, CH2M HILL employees who the company helped fund to lend their expertise and experience to the project. (See Friesen’s compassionate video about the project.) Typically, Water For People measures impacts by studying the nuts and bolts of their projects, such as water quality monitoring and needs assessment. For the first time, Water For People asked for a comprehensive, business-focused look at how this project created access to financial and social capital that makes their intervention in the community sustainable in a scalable and replicable way.

Identify the Need & Design the Program

From the start, community members were active participants in developing water and sanitation projects for their village. Local people made decisions to increase water and sanitation availability for the village, took ownership of and accountability for the facilities and created a maintenance fund to continue operations into the future. Many communities had a well system in place that was capable of providing clean and fresh water; however, community members faced tremendous difficulties in operating and maintaining the wells. If a part broke, it could be one to two months before it was repaired or replaced by the government. Finding someone to fix the system was a struggle. In the meantime, people returned to using contaminated water sources or were forced to travel long distances on foot to alternate water points.

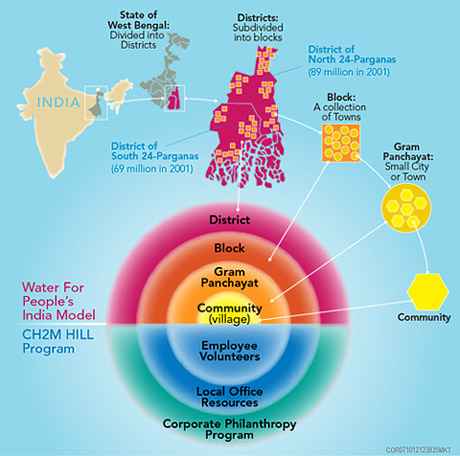

The State of West Bengal is divided into districts then into several blocks or collections of cities and towns much like counties in the United States. These blocks are further subdivided into small groupings of local communities (often towns) called Gram Panchayats. It became clear during the learning phase that each of these levels of government would be important in creating a successful program, as Gram Panchayats and blocks differ in their funding and operations. Likewise, from a business partner perspective, CH2M HILL needed to engage at multiple levels to leverage its investment of time and money in supporting Water For People’s mission – from the corporate level through philanthropy to the local office level and as individual volunteers.

Within a given community, each water source has a water and sanitation committee (WATSAN) that owns and stewards the water source. WATSANs are an integral component of the sustainability of water systems and are involved in all phases of the project from planning to implementation, operation, maintenance and monitoring.

© CH2M HILL | Only by leveraging across multiple structures at different levels can durable relationships be created to foster sustainable, lasting water and sanitation systems. This applies to both NGOs working on the ground and corporations providing philanthropic support.

“When we had meetings with WATSAN committees and went into communities, they understood that the idea of taking control of their own future is more powerful than intermittent periods of charity,” said CH2M HILL volunteer Strand. “These people have a strong entrepreneurial sense and were receptive to taking control. But, what they needed from us was to learn how to structure a system so they could get quality parts quickly, get enough money to keep themselves going without credit and simply get started.”

Build Skills, Stimulate Demand & Facilitate Capital

WATSANs collect maintenance funds from users to contract with a “jalabandhu,” which translates to “water friend” in Bengali. Jalabandhus are mechanics who maintain water systems and can be called upon for repairs. The goal of the jalabandhu program is to meet the scarcity of hand pump mechanics and reduce downtime of the water system. Currently, 114 jalabandhus serve seven blocks of approximately 210,000 residents.

Water For People brought in skilled people who could teach jalabandhus how to service wells. This teaching step is a short-term, low-commitment investment that builds social capacity and local knowledge. Once the community sees the benefit of this knowledge – wells repaired quickly – demand for these services is stimulated. At that point, jalabandhus need access to capital to buy parts, bikes, tool bags and equipment so they can respond to calls and conduct repairs as an entrepreneurial business. This is where money collected by WATSANs comes in. People become invested in their local water supply and pay to maintain it.

“The good news is that the jalabandhu system has reduced pump down-times from many days to only a few hours,” said CH2M HILL volunteer Friesen. “However, a few problems still exist. For example, locally available parts are poor quality and some communities wonder why a part fixed a short time ago needs to be repaired again. Jalabandhus want to work together to import better quality parts so they can make better repairs.”

Another common issue is not having enough tool kits to repair all types of pumps currently installed. Kits are expensive and beyond the financial means of jalabandhus. It can be difficult for them to work effectively (and to get paid) in communities that do not have WATSAN committees to organize and collect fees.

© Jeff D. Friesen | WATSAN committee members in their Water For People uniforms fill glasses with clean water at Purbachal Balika Vidyapith Girls’ School, Nadia, West Bengal.

Recognizing the importance of WATSAN committee and maintenance fees, Gram Panchayat and block governments have promoted WATSAN committees for all water sources so every water system will have an independent maintenance system.

“Water For People-India and its partner NGOs ensure participation of local government from the planning phase to implementation. The jalabandhu program has, therefore, been designed jointly with local government,” explained Satya Narayan Ghosh, senior program officer from Water For People-India. “Both local government departments and people’s representatives act as a bridge between jalabandhus and water system users so users can get their water system repairs when needed.”

According to Friesen, “The jalabandhu program is complex, and we don’t expect that one model will fit all circumstances when considering expansion. It’s very clear, however, that the program works. Drinkable water is flowing more consistently and in a more sustainable way with the jalabandhus’ help.”

Seeing the outcome and effectiveness of the jalabandhu concept for maintaining the water system, the government department has provided the required tools to existing jalabandhus, thereby enabling them to repair all types of hand pumps. The government has also asked Water For People to provide the necessary technical support so they can scale up this program in additional geographical areas beginning with the state government of Bihar.

Teach the Next Generation

If the goal of sustainability is to deliver a better world to the next generation, then the next generation must be prepared to receive it. Part of building local capacity, therefore, includes working with students. The goal of Water For People’s school projects is to institutionalize the concept and requisites of water and sanitation facilities aligned with the actual needs of the children.

“School children are active participants in WATSAN committees and teach other students about sanitation and hygiene,” said Andrew Britton, World Water Corps® manager. “They also act as a pressure group in the village community, especially for their parents, to create better sanitation facilities and to adopt improved sanitation and hygiene practices.”

Both children and teachers are involved from the beginning to define their desired water and sanitation facilities. Students work together in school to draw a plan, which is then finalized by an engineer. To construct the project, the government and school share 50 to 60 percent of the total cost and the remainder is funded by Water For People. Parents and school management jointly determine ongoing maintenance costs. On average, each student contributes 10 rupees annually.

Water For People foresees a challenge in the long-term sustainability of interdepartmental coordination within the government system. To meet school water and sanitation needs, it is critical for government departments, such as sanitation, water, education and local government, to work together because none can fund these needs alone. Water For People is making a continuous effort to influence these organizations to revise their school water and sanitation policies and execution strategy.

Measure the Impact

© Jeff D. Friesen | A jalabandhu with his transportation. The banner advertises his services.

To make the leap from a jalabandhu program within one district to spreading the model across multiple districts, Water For People needed to objectively assess the program. In their evaluation of the model in terms of sustainability, the World Water Corps® team found the initial intervention of external benefactors designed to be temporary with supporting funds reduced every year. The program model has resulted in long-term, permanent, sustainable and beneficial impacts to jalabandhus and communities in which they live and provide services.

A key component of jalabandhu success is the program “takes local people and trains them to inject knowledge, awareness, advocacy and dollars into the community to fill a gap where government falls short. This sustainability model sets Water For People apart,” explained Friesen. “Water For People is trying to put themselves out of business wherever they go. Specific to India and jalabandhu, a minimal investment creates large social impacts for the long-term and a source of pride and ownership.”

The evaluation report has also helped Water For People and the concerned government departments better understand the opportunity for working with community-based, women-managed, micro-financing organizations with a revolving fund for improving sanitation services.

“The report has helped validate some of our plans for the program like creating a central call center for the jalabandhus,” said Water For People’s Satya Narayan Ghosh. “Suggestions in the evaluation report were useful in identifying prevailing gaps, requirements to strengthen the program and factors needed to continually improve the program. This includes things like promoting those already in business rather than bringing in new people and influencing local government to promote user committees to hire services at any time.”

Local Vision Triggers Corporate Giving

CH2M HILL has partnered with Water For People for 21 years and has provided in-kind assistance and volunteers as well as philanthropic donations. However, the firm’s India Managing Director, Pawan Maini, had a deeper relationship in mind when he joined the Water For People International Board of Directors in 2011. “I’m most excited about helping Water For People capitalize on opportunities to expand its services in India. The impacts on quality of life for India’s citizens and its economy will be immense.”

Maini approached CH2M HILL’s company leadership with a proposal to assist Water For People with an integrated program to deliver a community and school safe water supply, sanitation and hygiene education program to West Bengal. For this partnership to work, it would require a targeted donation, involvement from Maini at a professional level and the help of volunteers like Friesen and Strand. The goal was not just to build systems but to build the capacity of communities and schools so they would have the skills needed to operate, manage and maintain their new or rehabilitated systems.

CH2M HILL’s goal was to help Water For People leverage a fairly modest investment of $150,000 to make the most sustainable impact possible. To do this, the firm tapped into not only its financial resources but also its leadership and expertise in sustainability, and its “human capital.” With its India Managing Director working in-country, the firm relied on Maini’s local knowledge, insights and connectivity to help leverage its investment in Water For People. Taking a holistic approach to providing financial as well as leadership engagement and volunteer support brought greater value to Water For People than simply writing a check. On the flip side, it also offered opportunities for greater employee engagement and benefit to CH2M HILL.