WINTERS: 1970-1980; Robert Glenn Ketchum’s First Published Portfolio

With his first published portfolio, WINTERS: 1970-1980, Robert Glenn Ketchum challenged the established status quo of landscape photography. He achieved this by rejecting the iconic “view” in favor of a record of his experience and by replacing the traditional large format camera with the lesser regarded 35mm camera. Ketchum created a visual library where descriptive content was not as important as perception, feeling and concept. This same spirit was incumbent in the Los Angeles art scene as the Second World War came to an end and life began anew. These thoughts were aptly reflected in Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980, an initiative of the Getty in partnership with more than 60 cultural institutions across Southern California. These multiple, complimentary exhibits, which began in 2011 and ended spring of 2012, surveyed the birth of the Los Angeles art scene and how it became a major new force in the art world. Each of the institutions participating in Pacific Standard Time assembled an exhibit that explored and celebrated Los Angeles-based artists who contributed to this emergence.

Work from Ketchum’s WINTERS: 1970-1980 portfolio was included in one of the exhibits at the University of Southern California-Fisher Museum of Art. That exhibit highlighted important contributions to the L.A. photographic community made by the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies, where Ketchum served as director and board member for many years. Below are comments from Ketchum explaining his thoughts, methods and creative process during those historic times of change as he created his WINTERS portfolio.

|Avalanche Lake Basin, 1974

Avalanche Lake Basin (Cirque Headwalls in a Blizzard), 1974, my print selected for the USC exhibition, was one of 24 images in my first published portfolio – WINTERS: 1970-1980. At the time I created and exhibited this work, it challenged the accepted status quo of how we perceived photographs made in nature and what the purpose of those photographs might be. In 2006, when the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, hosted my 45-year retrospective, Curator John Rohrback highlighted this portfolio as one of the first post-modern works based in nature and referred to the winter images as “anti-landscapes.”

|View in a Storm, 1973

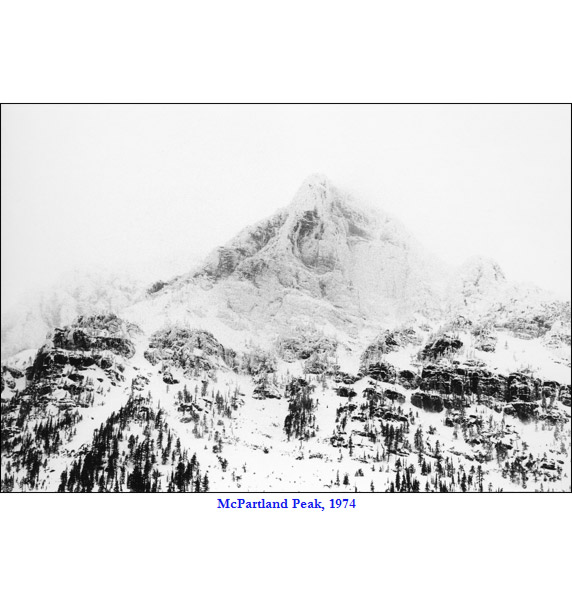

The 24 images in WINTERS: 1970-1980 were created in the years following my graduation from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA, BA, ’70), after which I moved to Idaho. While enduring a decade-long commute, I maintained an active relationship with a group of Idaho friends, who were hikers, climbers and adventurous backcountry skiers, while pursuing technical courses at the Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara and a graduate degree (MFA ’74) in photography from California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). This portfolio of images was created during many different backcountry adventures in which my friends attempted winter ascents of several significant summits and expedition-style range traverses, often of multiple-day duration.

|Approaching Storm, 1971

The background for this work includes my study with two very inspirational and experimental teachers at UCLA, Edmund Teske and Robert Heinecken. Both communicated their passion for the medium and their personal desire to push its boundaries. Eliot Porter and I exchanged letters about color and natural light, and, ultimately, I visited him and Paul Caponigro in New Mexico. Not insignificantly, Ansel Adams was viewed as North America’s penultimate landscape photographer by the media and collectors, and was featured on the cover of TIME magazine as well as in the first American television ad for Toyota.

My graduate work at CalArts was informed by the birth of the feminist art program and the emergence of the post-modern aesthetic. It was also CalArts’ mentor/instructor Alan Kaprow, recognized as an artist for his “happenings,” who suggested that just my effort to exist and to create in the places my pictures depicted, constituted artistic performance.

|Snowfall, 1979

Lastly, I was inspired by, and part of, a growing community of West Coast photographers and practicing artists who were remarkably diverse in their interpretation of the photographic image. I worked with many on a regular basis at the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies where we also published and exhibited historical collections and nationally recognized contemporaries.

Despite the very progressive nature of the artistic moment, landscape photography in the late ’60s and early ’70s was dominated by the “School of (Ansel) Adams,” his peers and historical predecessors. My colleagues – even some producing quite experimental work themselves – seemed to accept that the landscape was exclusively the domain of the large format view camera and broad tonal latitude sheet film.

It was repeatedly expressed to me that I should be using a view camera if I expected to have my work “taken seriously” and that I could never “get what I needed” from the tonality of the smaller, 35mm role film. The 35mm format allowed me to explore a world of landscapes none of my predecessors even considered as subject matter – one quite different from the benign-weather, convenient-access, point-of-view typical to the larger cameras.

In New York City, Lee Friedlander, Gary Winograd, Joel Meyerowitz and Ernst Haas were using their 35mms to witness the spectacle and color of life on the City’s street. Embracing the unique aspects of the smaller format helped them to capitalize on spontaneity, as did higher shutter speeds and greater choice of lenses. The ability of roll film to achieve multiple exposures quickly also allowed tonal control through exposure-variation and sequential photography. Their images were redefining how we viewed the world. These same attributes appealed to me as well; however, I was witnessing a very different part of the world.

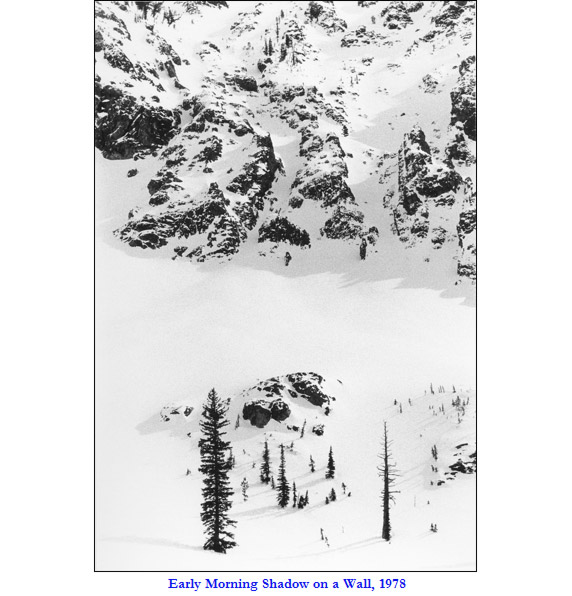

|Peak above a Cloud, 1973

The winter world in which I was immersing myself was in a constant flux of changing weather and conditions. Existence was a kind of perpetual motion. Daylight hours were short. Stopping to ponder only made you cold. In most circumstances, snow depth was great enough that establishing a tripod would have been impossible. Simply setting-up a view camera invited frostbite. Over multiple days of exposure in such conditions you became less exact in your personal functionality, and view cameras with their metal accessories simply froze-up and became unusable.

Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, William Henry Jackson, their peers and, in later generations, Adams and Porter either had entire entourages helping them, or they were working with assistants. These necessities for them were not an option for me. To do what we were doing, my colleagues and I each carried what we needed with regard to food and gear. We were alpine adventuring and we succeeded because we were mobile and self-contained; there was little room for additional weight or bulk. At the time, new technologies in clothing insulation and food preservation allowed us to exist and enjoy very challenging environments. As an artist, the same was true of the smaller camera, which was allowing me a new and unique point-of-view. I was quite intentionally using a format I felt best suited to translate what I witnessed. And, the result is a kind of visual “wildness” my predecessors seldom saw, let alone chose as subject matter.

|Sheer Wall, 1977

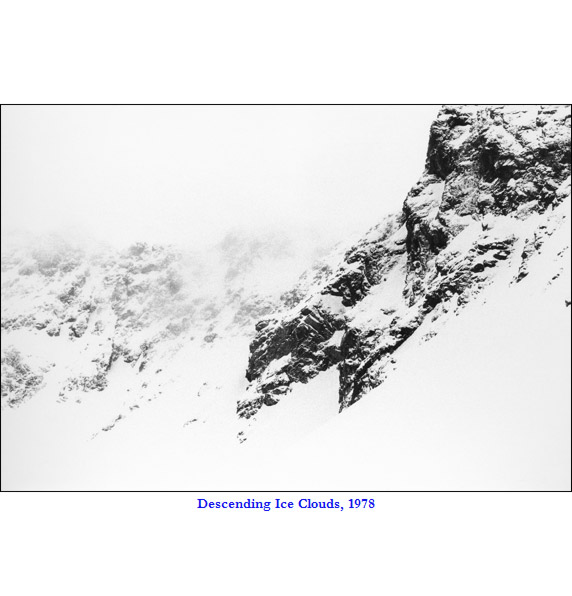

With regard to film, 35mm was viewed as “grainy” by comparison to larger format sheet film, and it was felt to lack the tonal capacity as well. In fact, my film of choice – Kodak Tri-X – specifically had more grain than other 35mm films I could have selected. But, I used it because its grainy structure suited my nebulous, ephemeral, falling-snow-speckled subjects. It also suited my printing intentions. These images were jewel-like to me, thus demanding closer, careful observation to truly be appreciated. So, most images in the portfolio were never printed larger than 5″ x 8,” which made irrelevant any consideration of film grain becoming more distracting as enlargement increased.

Specific control of tonal latitude in large format is possible because each sheet of film is processed separately. This allows development time to be adjusted to suite lighting conditions and, quite literally, to control those conditions. Using this technique, every image can be manipulated by processing to render the broadest tonal latitude possible and that “full-tone” concept defined “good” black & white printmaking at the time. The “School of Ansel Adams” would certainly have had us all believe that every picture had black, white and 12-15 shades of grey. Part of my purpose in this portfolio was to question that.

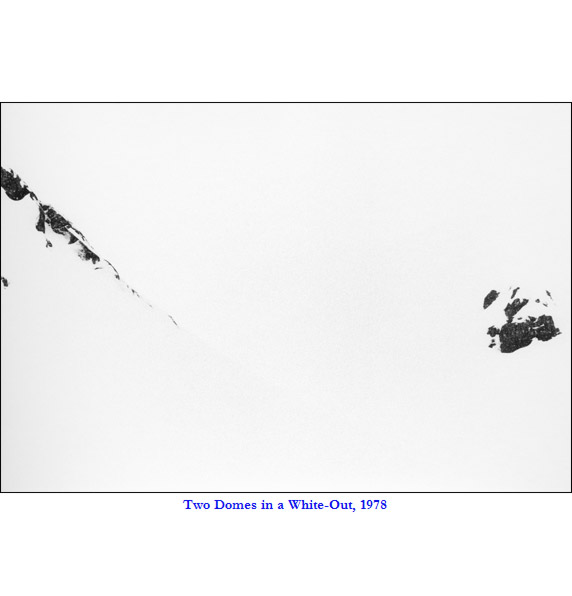

|Chute Detail, 1974

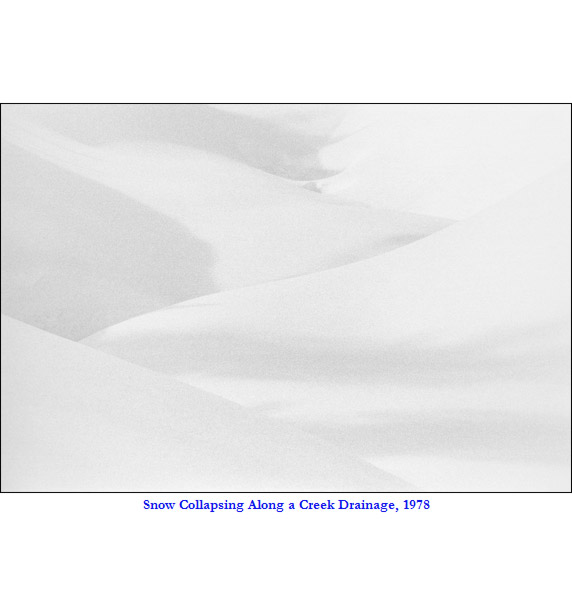

Given the environment and conditions in which I chose to work, there were many days when no such tonal range existed and some days where there were hardly any tones whatsoever. The lack of those tones was essentially part of the reason to make the picture.

Having said that, elegant tonality still gives a print its beauty, so it was important to optimize processing of the 35mm film I was shooting. Commercial roles of Tri-X were either 20 or 30 exposures to the roll and, with so many shots to the roll, it inevitably meant some subjects exposed in one light would benefit from perfect development while other subjects in different lighting would likely suffer. The supposed advantage of large format sheet film – allowing specific processing for each and every sheet – thus accommodated producing the best tonal range for all lighting circumstances. To achieve this same control in 35mm, I simply rolled my own Tri-X. With only five or 10 shots to the roll, I would then shoot the entire roll in the same lighting conditions and process each roll individually, thus achieving the control over tonality expected of larger formats.

The limited tonal range apparent in the select images of this portfolio is not a high-contrast printing effect. It is an attempt to render the scene as actually viewed instead of manipulating technology to represent an idealized interpretation of the landscape. For the record, my preferred printing papers were DuPont Velour #2 and #3, and Agfa #3 and #4 – all rich tonal printing material.

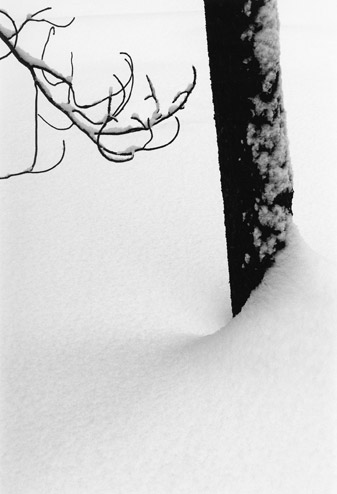

|Visual Haiku, 1977

WINTERS: 1970-1980 was my reaction to the domination of the view camera in landscape photography and the concept that all prints should express a full tonal range. As importantly, these images were a rejection of the iconic view, the grand scene.

British painter J.M.W. Turner believed his atmospheric canvases expressed his actual experience of the subject, his personal immersion in that landscape or storm that stimulated and informed the work. Similarly, my images are not about “views” of a “beautiful” place, but, rather, they are an attempt to translate my experience of a dynamic landscape through film to print. These photographs do not define location; they explore mood and mystery using atmosphere, tone and form. In fact, these images are so foreign and abstract to a general audience that titles are simply explanations of the event being witnessed and intentionally lack any description of place.

|Hard, Driven Snow, 1979

The portfolio WINTERS: 1970-1980 is comprised of 24-5″x 8″ silver gelatin prints individually mounted on de-bossed rag pages with letter-pressed titles and dates. The images were created with a 35mm camera, and every image/print is represented full frame as seen in-camera at the time of making the picture. The mount pages and portfolio box design honor and accentuate the rectangular aspect of the 35mm film. This absolute in-camera framing and printing has remained a signature of my career, regardless of the cameras I have used.![]() Issue No. 23, 2012

Issue No. 23, 2012

Distant Wall through Snow and Clouds, 1977

The Corcoran Gallery of Art (D.C.)

National Museum of American Art (D.C.)

Amon Carter Museum (Texas)

Hudson River Museum (N.Y.)

Huntington Library, Gardens and Collections (Calif.)

Museum of Modern Art (N.Y.)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Calif.)

Museum of Contemporary Art (Calif.)

University of Southern California (USC)-Fisher Museum of Art (Calif.)

Minneapolis Institute of the Arts (Minn.)

Henry Gallery of Art (Wash.)

Robert Glenn Ketchum’s WINTERS Slideshow